Every once in a while, someone writes something that makes a murky, complicated, frustrating issue seem crystal clear.

This post by Eric Fischer is one of those. Doing yeoman’s work, Fischer transcribed decades’ worth of San Francisco housing prices and other data. Among his findings:

- Though we talk about the Bay Area’s housing crisis as if it were a recent phenomenon, Fischer finds that housing prices have been appreciating at a steady 6.6 percent pace for the last 60 years. In real terms—that is, adjusting for inflation—they’ve been appreciating at about 2.5 percent annually. That doesn’t sound like much, but when it happens for 60 years in a row, it means that housing prices have quadrupled, after inflation, since 1956.

- We know that housing prices are the result of exceedingly complex market and regulatory systems. But Fischer shows that variations in price over the last four decades can be predicted pretty well using just three variables: employment growth, wage growth, and housing construction.

Both of these have obvious follow-up questions—which Fischer asks and (mostly) answers.

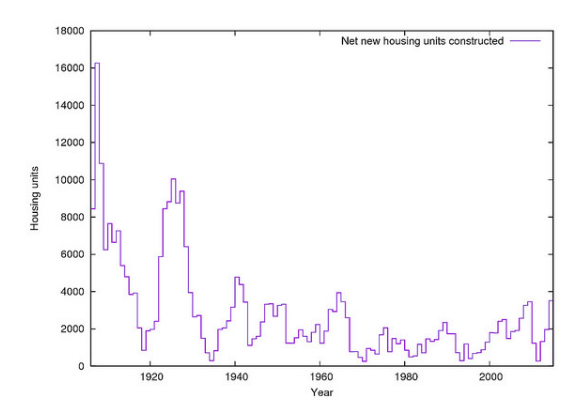

First, if San Francisco’s housing crisis actually started 60 years ago, what triggered it? Well, the housing construction cycle that ended in 1954 was the last in which the city had large tracts of greenfield land. After that, housing could really only be added at scale with infill—but by then, zoning had already been enacted to make that much more difficult. In other words, because it has been unwilling to allow large-scale redevelopment, San Francisco has been steadily under-building basically since it ran out of open land.

Second, if you can mostly predict housing prices with just three variables, how much influence does each have? Of course, correlation is not causation, and as Fischer admits, small tweaks to the model could produce notably different results—so these should be treated as broad trends, not precise measurements. But in Fischer’s model, a one percent increase in employment is associated with a 0.95 percent increase in rents; a one percent increase in wages is associated with a 1.74 percent increase in rents; and a one percent increase in the housing stock is associated with a 1.70 percent decrease in rents.

If we treat those as roughly accurate, that suggests that to return to 1981-era prices, when inflation-adjusted rents were about two-thirds lower, employment would have to fall by 51 percent, or wages would have to fall by 44 percent, or the housing stock would have to grow by 53 percent.

Michael Anderson of Bike Portland took a look at these numbers and despaired. And he’s not wrong: clearly losing half of all the jobs in San Francisco, or cutting everyone’s income in half, would be disastrous; and building 200,000 new units of housing in a city that permitted just over 3,600 last year seems more than a little out of reach. (And of course, every year that employment or wages rise, that needed housing number goes up, too.)

But Anderson also points out that even if there were no regulatory constraints on building housing, development would surely grind to a halt way before prices could fall down to semi-reasonable levels, as developers realized they could no longer count on the rental revenue they had based their loans on.

In fact, this brings up a point that is often elided when we talk about places, like San Francisco, where prices have gotten totally out of control: A rapid “correction” to those prices would, in many ways, be an economic crisis. Nearly every homeowner would find themselves tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars underwater on their home, probably causing a massive region-wide foreclosure crisis; renters would also be affected, as their landlords would also be underwater or even bankrupt, many stuck with mortgages based on valuations that anticipated rents three or four times higher than their new, more reasonable levels.

In America, no democratically elected government could ever propose, let alone enact, a policy with these consequences. Rather, San Francisco’s best hope is to build enough to prevent more price increases above inflation, and maybe even keep price appreciation below inflation, so that over the coming decades prices can float down to a more reasonable level without ruining every property owner in the city—and, in the meanwhile, produce as much non-market housing as possible. (Universal housing vouchers or housing tax credits would help.)

Fischer’s work, then, might best serve as a warning to other cities: housing crises, driven in part by supply shortfalls, build up over decades—and once they’ve been going on that long, the path back down the mountain is perilous and slow.