Zoning is complicated. It’s complicated on its own, with even small towns having dozens of pages of regulations and acronyms and often-inscrutable diagrams; and it’s complicated as a policy issue, with economists and lawyers and researchers bandying about regression lines and all sorts of claims about the micro and macro effects of growth rates and whatever.

This post will not get into any of that.

Rather, this post will ask a very simple, first-order question that absolutely anyone, regardless of expertise or math skills, can answer just by pondering their own hearts and minds for a minute. This is, in other words, a gut-check moment, if you’ll excuse the mixing of anatomical metaphors.

The question is: Should zoning rule out virtually all of the kinds of buildings that already exist in your city or neighborhood? In other words, imagine taking a walk around the block where your home is. All those buildings you see: Are they so terrible that you’d like to pass a law making it illegal to build them again?

This may seem like a silly question. After all, local officials and neighborhood groups often rely on regulation to “preserve community character.” Isn’t the point to encourage the kinds of buildings that already exist?

But—especially in places that were largely built up before World War Two—that is often not what building regulations do. Take, for example, Somerville, Massachusetts, an inner-ish ring suburb of Boston. Somerville is the kind of in-between density that you’ll often hear people praise: compact enough to walk to stores and friends’ houses, but with virtually no buildings over four floors, lots of trees and yards, and a mix of small apartment buildings and single-family homes.

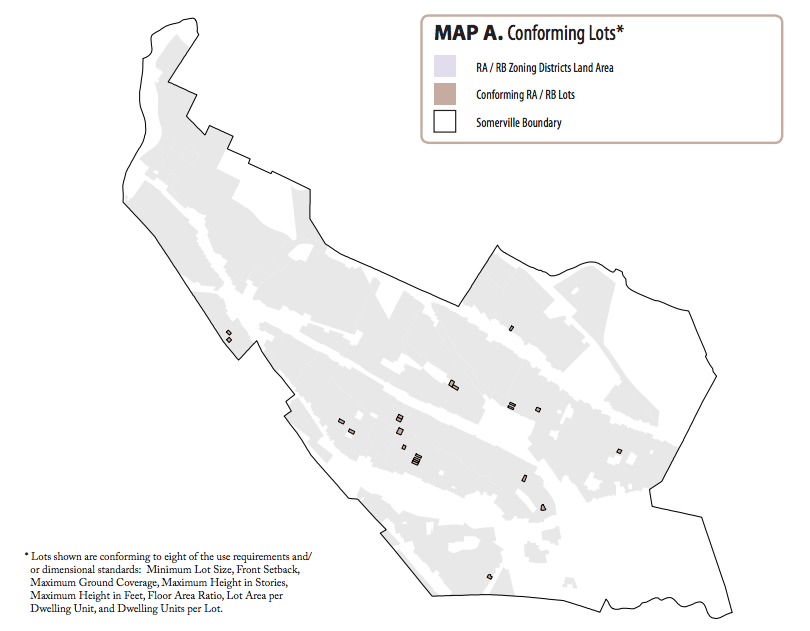

But recently, the Somerville planning office released a report in which they confided that, in a city of nearly 80,000 people, there are exactly 22 residential buildings that meet the city’s zoning code. Every single other home is too dense to be legal: Either it takes up too much of the lot, or it has too many homes, or it’s too tall, or it’s not set far back enough from the street, and so on. (Note that this calculation actually doesn’t include parking requirements, which might very well do away with those last 22 conforming buildings.)

Is Somerville really such a dark, dystopian place that the entire city ought to declare itself illegal?

No. Although my question above really is an open one—I don’t know where you live, and maybe your neighborhood really is that awful—my guess is that for the vast majority of people, the discovery that your city had declared your home and all your neighbors’ homes too deviant to be legally allowed would come as something of an unpleasant surprise. It might also make you think that, at some sort of fundamental, does-two-plus-two-equal-four level, something had gone wrong with the way your city regulates buildings.

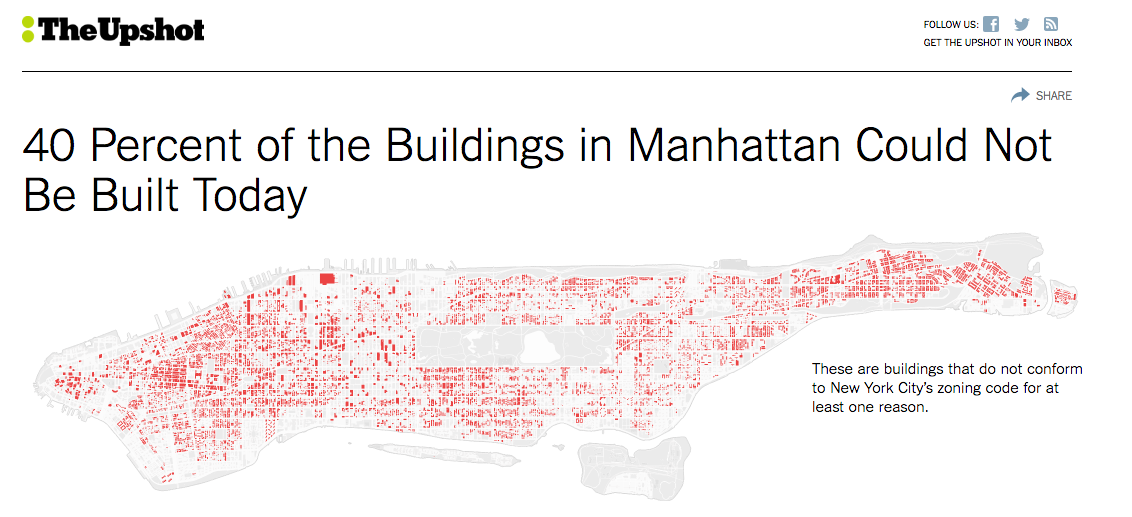

And I think that, for most of you, that impulse would be correct. And while Somerville may be an extreme case, chances are pretty good that if you live in an area where most buildings are at least 60 or 70 years old, your situation is not entirely different. Only a few weeks ago, the New York Times discovered that fully 40 percent of all the buildings in Manhattan would be illegal to build today. Last year, we published a Portlander musing on how all the things he loved about his long-established urban neighborhood—its density, diverse mix of uses and housing types, and buildings built up to the sidewalk—were the things even that city had subsequently declared illegal. And near where I live, in Chicago, it’s quite common to find entire blocks that have been apartments since at least the 1920s, where the city has declared that the only “compatible” kind of building is single-family homes. “Compatible” with what?

Don’t worry: City Observatory will get back into the econometric weeds soon, probably in our next post. But it is valuable, from time to time, to step back and gawk at the big picture of contemporary land use law, which has taken its mandate to protect people from dangerous or noxious buildings and ended up declaring that the neighborhoods where tens of millions of people live—neighborhoods that, if surveys and housing prices are to be believed, many people consider pleasant and desirable—are themselves dangerous and noxious. There is something wrong here that you don’t need an economics or planning degree to understand.

This post appeared originally on City Observatory in June, 2016.