At least on the surface, the big declines in gas prices we’ve seen over the past year seem like an unalloyed good. We save money at the pump, and we have more to spend on other things, But the cheap gas has serious hidden costs—more pollution, more energy consumption, more crashes and greater traffic congestion. There’s an important lesson here, if we pay attention.

US macroeconomic forecasters are usually very upbeat about any decline in gasoline prices.

Because the US is a big importer of petroleum, a decline in oil prices benefits the US economy. Lower oil prices reduce the nation’s balance of trade deficit, and effectively put more income into consumer’s pockets, which helps stimulate the domestic economy. In theory, declining gas prices should have the same stimulative effect as a tax cut. Whether that’s true in practice depends on how consumers respond to changing gas prices. Some of the positive effect of the decline has been muted by consumer disbelief that price reductions are permanent. Earlier this year, surveys by VISA showed that 70% of consumers were still wary that prices could rise.

But cheaper gas has does free up consumer budgets to spend more in other industries. Using data on credit card and debit card purchases of households, and looking at variations in spending among households that spent a little and a lot of their income on gasoline, and observing how spending patterns changed as gas prices fluctuate led the JP Morgan Chase Institute to predict that the bulk of savings from lower gas prices go to restaurant meals, groceries and entertainment.

Locally, the effects can be different. In oil-producing regions, as the saying goes, your mileage may vary. Declines in oil prices have produced a sharp fall off in revenue, drilling activity, and jobs in places like Texas, Oklahoma, North Dakota, and Alaska. Recently, Shell Oil shelved its plans to drill for oil in the Arctic because it couldn’t justify the expenditure based on the current (and expected future) price of oil.

But while the macroeconomic news is mostly good, the microeconomic news is quite different. As we noted earlier, the demand for driving—and therefore gas consumption—is sensitive to the price of gasoline. Declines in gasoline prices encourage increases in driving. And more driving has all kinds of negative consequences that end up imposing costs on all of us: more traffic congestion, more injuries and deaths from crashes, and more pollution.

What’s happening now is the flip-side of the big declines in driving we experienced when gas prices went up. We haven’t tend to overlook the silver-lining associated with higher gas prices. For example, the reduction in vehicle miles traveled (VMT) that followed the advent of $3 and $4 a gallon gas prices was far more effective in reducing congestion than any highway expansion program. In large part, that’s because traffic congestion is highly non-linear, meaning that a small drop in the number of vehicles on the road can produce a proportionately much larger drop in congestion. According to travel tracking firm Inrix, in 2008, the 3 percent decline in VMT traveled led to a 30 percent decline in traffic congestion. As gas prices fall and driving increases, those gains may disappear.

Much more serious is the toll of deaths and injuries from crashes. Traffic fatalities, which had steadily decreased as driving ebbed, have recently been on the uptick as well. In Oregon, traffic fatalities have jumped to levels not seen in seven years—before the big run up in gas prices in 2008. In the first seven months of 2015, Oregon traffic fatalities were up 44 percent over the first seven months of 2014 (the period immediately prior to the decline in gas prices). Nationally, a 14 percent rise in crash-related fatalities has surprised insurers and pushed up car insurance premiums. A detailed study of gas prices and crashes in Mississippi found that a 10 percent increase in gasoline prices was associated with a 1.5 percent decrease in crashes per capita, after a lag of about 9-10 months.

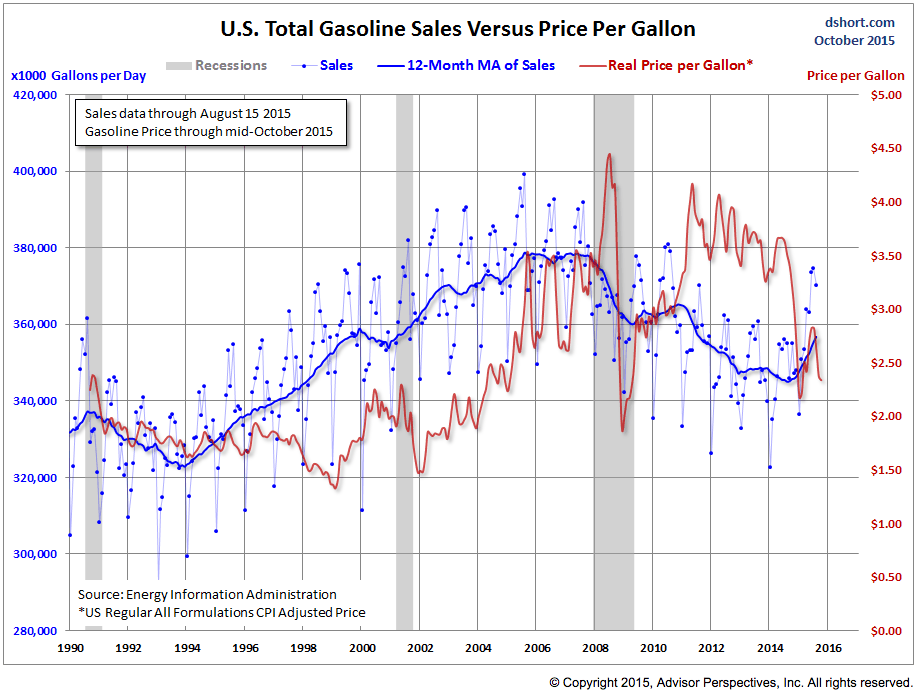

Lower gasoline prices also mean we’re burning more gas and creating more pollution. Overall US gasoline consumption, which had been trending down for years, bounced back up in 2014 just as gas prices collapsed:

Gasoline sales increased by about 10 million gallons per day over the past year, since each gallon contributes about 19.6 pounds of carbon dioxide, that means increased driving has led to about 35 million additional tons of carbon per year emitted into the atmosphere. This surge in driving has contributed to a reversal in the steady declines in total CO2 emissions the nation recorded in the years after 2008.

On top of it all, cheaper gas is prompting drivers to buy less fuel-efficient vehicles. Sales of of light-duty trucks are up sharply, and average fuel economy of new cars, which had been steadily improving, has fallen noticeably in the past year. According to researchers at the University of Michigan, the average new car today is rated at 25.0 miles per gallon, down from a peak of 25.8 miles per gallon in August 2014. Cheap gas today gets “locked in” to higher fuel consumption over the 15 or 20 year life of these less efficient vehicles.

There’s plenty of downside here, but if we pay attention, there’s also something we can learn: gas price fluctuations represent a terrific natural experiment in the efficacy of using pricing to manage traffic and its negative effects.

Of course gas prices are a fairly crude way of reflecting back to drivers the costs of their behavior. Gas prices don’t reflect the time of day traveled or whether the road is congested, and have far less impact on the behavior of owners of high-efficiency vehicles. But as blunt as the incentives are, they show that discouraging just a small amount of travel at the peak hour can result in big reductions in time lost to congestion and in lives lost to crashes.

The uptick in driving—and all its associated costs—resulting from the decline in fuel prices is powerful evidence of the effectiveness of pricing and demand management strategies in addressing the nation’s transportation problems. Our conventional approach to transportation consists almost entirely as “supply-side” measures: we build more roads, expand transit, and so on. But there’s another way to bring supply and demand into balance: to reduce demand.

TDM—travel demand management—is the neglected stepchild of US transportation policy. We have a few, fragmentary efforts, that are tried mostly in the breach: such as HOV (high occupancy vehicle) and HOT (high occupancy toll) lanes on a few congested urban freeways. In practice, they’re overwhelmed by cheap gasoline—and similar policies, like parking subsidies, which encourage more driving and actually make congestion—and pollution and crashes—worse.

Ultimately, there’s an important lesson here: prices matter. We neglect the most powerful and direct ways of managing demand—raising the price of driving, particularly on congested roadways and at the peak hour. Our recent experience with $3 and $4 gallon gas shows that we can reduce the demand for travel in ways that reduce traffic congestion, decrease the number of crashes and improve the air. Maybe it’s time to make that a conscious aim of transportation policy, rather than the by-product of oscillations in the global oil market.

In the meantime, enjoy your cheap gas: you’ll be paying for it in the form of more clogged roads and more crashes and deaths, less efficient cars and more pollution.