At City Observatory, we’re big believers that many of our transportation problems come from the fact that our prices are wrong – and solving those problems will require us to get prices right. While we desperately need a way to pay for roads that better reflects the value of the space we use, just moving to a new model isn’t enough. If we don’t get the new pricing system right, it could make many of our transportation problems worse. As the old adage goes, the devil is in the details.

In short, American cities have too much traffic today for the same reason that the old Soviet Union always had bread lines: we charge too little for a scarce and valuable commodity. As a result, people consume too much, and we end up rationing access by making people wait.

The main way we price road travel today is the gas tax, but it doesn’t send the right signals to travelers about how much different kinds of travel, in different places, at different times, actually cost. In contrast, the proposal to replace the gas tax with a vehicle miles traveled (VMT) tax – directly charging people by how much they drive – is clearly a step in the right direction.

With great fanfare, the State of Oregon announced its road pricing demonstration program, OReGO, on July first. Under this voluntary program, up to 5,000 motorists will sign up to pay a per mile fee of 1.5 cents rather than the current 30 cent state gas tax. Motorists will have two different options for monitoring their mileage: one that periodically reads the vehicle’s diagnostic data port, and another that uses GPS technology.

Over at CityLab, our friend Eric Jaffe is enthusiastic about this kind of mileage-based road fee, listing 18 reasons why they’re a good idea. While the concept of charging more for the roads, and charging in a way that reflects the cost of use – including contributing to congestion, road damage, and pollution – is essential, Oregon’s proposed road use system does exactly none of these things. The crux of the problem is that 1) it raises no more money than the current gas tax, and 2) it ends up subsidizing heavier, more polluting vehicles while actually punishing lighter, more fuel-efficient ones.

For many, the primary reason to favor a VMT tax is, as Eric Jaffe puts it, to “raise a gargantuan amount of money.” That would replace the gas tax, which, according to accepted political wisdom, is a dying revenue source. But VMT may not be a revenue panacea.

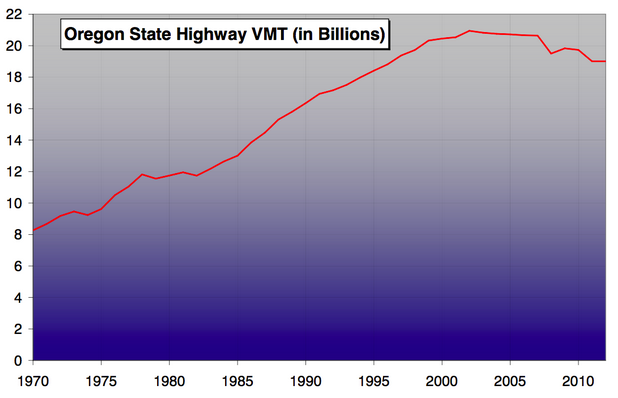

For one thing, total driving in the US is declining. Moreover, if we tied the tax to VMT—and set the tax at a high enough level to produce the “buckets” of revenue that proponents want–we’d expect that people would do what they normally do when something gets more expensive: do less of it. From a transportation perspective, this is a feature, not a bug. In Oregon, for example, even with increasing population, people are driving less now than they did a decade ago. As a result, a VMT tax would also have stagnant revenue growth–one of the same problems that plagues the gas tax. The data come from the Oregon Department of Transportation:

It also turns out that the gas tax is more proportional to the physical damage vehicles cause to the roadway and to the environment. A gas tax functions very much as a carbon tax (albeit a very low one): the more you pollute, the more you pay. But shifting to a tax based solely on mileage, without regard to how much pollution a vehicle creates, would essentially tax hybrids to subsidize hummers.

The flat, undifferentiated VMT fee would be like a butcher that charged a single price per pound for every cut of meat in the shop. You’d quickly find that you would have long lines of people lining up to buy steak and you’d end up throwing out over-priced hamburger that no one would buy. A key part of a VMT fee should be its ability to signal to users how much travel costs to society as a whole, depending on when, where and how they do it. A flat fee per mile, whether it’s in Manhattan, New York or Manhattan, Kansas, or at 5am or 5pm, will do nothing to encourage people to use cars at more efficient times or places, or to choose to take transit, bike, or walk instead.

Getting a VMT fee right is going to become increasingly important, because the problem of mis-pricing and under-pricing road use is going to become much worse in the years ahead. The business models of Uber and other “ride-sharing” services are predicated on very low-cost access to the public right of way.

Already, there is evidence that the growth of Uber and other for-hire vehicles is putting further strains on the very limited street capacity of New York. The number of for-hire vehicles in the city has grown 63 percent since 2011, and traffic speeds on Manhattan streets have fallen 9 percent since 2010. Slower traffic has resulted in slower rush hour bus service, and contributed to declining Manhattan bus ridership, which fell 5.8 percent last year.

The problem will mushroom if, as many expect, someone figures out how to build and deploy fully autonomous vehicles. If they aren’t charged for their use of the public right of way – both when carrying paying passengers, or when hovering in high volume locations – we’ll likely see even greater congestion of the roadway. Under-priced roads signal to road users–and innovative transportation companies–to over-use them, with potentially negative effects for the entire system.

We had a preview of this problem with the short-lived parking App, Monkey Park, which set up a way for people to auction off public, on-street parking spaces as they drove away. Unlike with Uber and Air BNB, San Francisco successfully imposed a cease-and-desist order, based on the premise that it’s illegal to sell public space. Monkey Park’s business model was predicated on extracting profit from an under-priced public resource—which is exactly what is at work with Uber and other businesses providing traffic in public streets.

It’s tempting to treat road pricing as just a way to raise more money for construction and maintenance. But that would be a huge mistake. If we get the prices right, we can make a significant dent in congestion by signalling to travelers how to make more efficient use of the roads we have, avoiding the need for expensive new capacity.

Already, we have good models of how this works with congestion pricing systems that vary by place and time of day in London, Stockholm and Singapore. San Francisco has implemented variable pricing for parking and has explored proposals to charge for vehicle miles traveled–based on time of day. And the evidence from earlier experiments in Oregon is clear, while a flat VMT fee has very little impact on peak hour travel, a fee that ranges from .4 cents a mile (off peak) to 10 cents per mile during peak hours in the central city would reduce vehicle miles traveled by more than 20 percent.

Our transportation problems are–at their root–a product of getting the prices wrong. If we adopt some kind of VMT fee, we have a once in several generations chance to get the prices right. Let’s not blow it by failing to make sure that the way we price roads and travel sends the right signals to everyone about how, and when to use the roads. The devil is in the details here.