There’s probably no better example of the faddish, “me too” approach to urban economic development than the pursuit by cities of every size for a slice of the convention and trade show business. Cities have built and expanded convention centers for decades, and in the past few years it’s become increasingly popular to publicly subsidize the construction of “headquarters hotels” near convention centers in hopes of drumming up further business.

As Heywood Sanders pointed out in a commentary at City Observatory in April, the consultant reports prepared to justify these convention centers and hotels are brimming with Pollyanna-ish optimism. But occasionally, even upbeat prose and glossy presentation can’t conceal some of the bitter truths about this industry.

The latest report we’ve seen was prepared for a proposed Milwaukee convention center expansion project by the Chicago-based firm of Hunden Strategic Partners (HSP). Copies of the report are available on the website of the Greater Milwaukee Committee, the study’s sponsors. It’s interesting reading–full of data about the convention centers of more than a dozen cities around the country, as well as the economics of the convention business. Here are some of the highlights, from our perspective.

The sales pitch has changed from hope to fear.

Traditionally, the rationale for building convention centers was to tap into the supposed motherlode of the growing convention center business. By getting a larger share of the growing market for conventions, the theory went, a city could create new jobs and generate additional income and tax revenue. Today, however, the message is much more grim: cities have to throw money at convention centers (and accompanying headquarters hotels) to avoid losing businesses to others. As Urban Milwaukee’s Bruce Murphy argues, the rationale for public investment is increasingly reduced to mimicking what other “peer” cities are doing. The sales pitch is now: expand your facilities because other cities are doing the same. There’s no expectation of growing profits or jobs; it’s all about avoiding losses and keeping up with the competition.

The convention market isn’t growing.

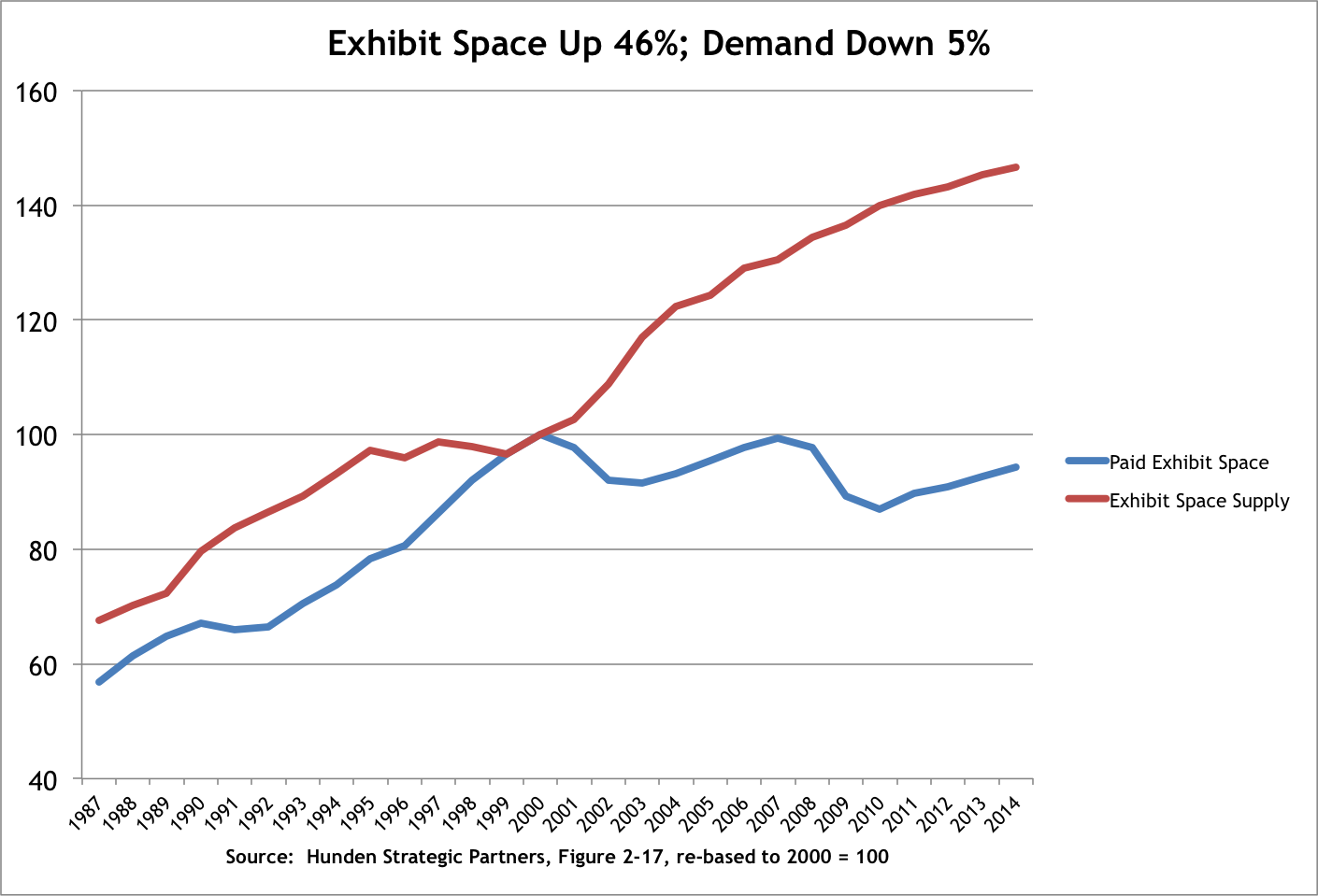

The key reason for the grim outlook in this business is that the overall market for conventions and exhibitions is simply stagnant. The peak year for the US convention business was 2000. Two recessions, and several generations of social media technology later (fifteen years ago, there was no Skype, Facebook, Twitter or Instagram), the market for exhibition space hasn’t grown at all.

The HSP report tries to put a good face on the data, claiming “Exhibit space supply has increased every year since 1999, however paid exhibit space rises and falls with the economy.” Since 2000, however, the “falls” have more than offset the “rises,” and as a result, while the supply of exhibit space has expanded by more than 45 percent, the demand for space in 2014 (blue line on the chart above) was still about 5 percent lower than it was 14 years earlier. As the report dourly concedes “the supply demand gap gives meeting and event planners an edge in negotiations.” Too much space chasing too few conventions is the real reason that so many cities are finding the convention business a consistent money-loser.

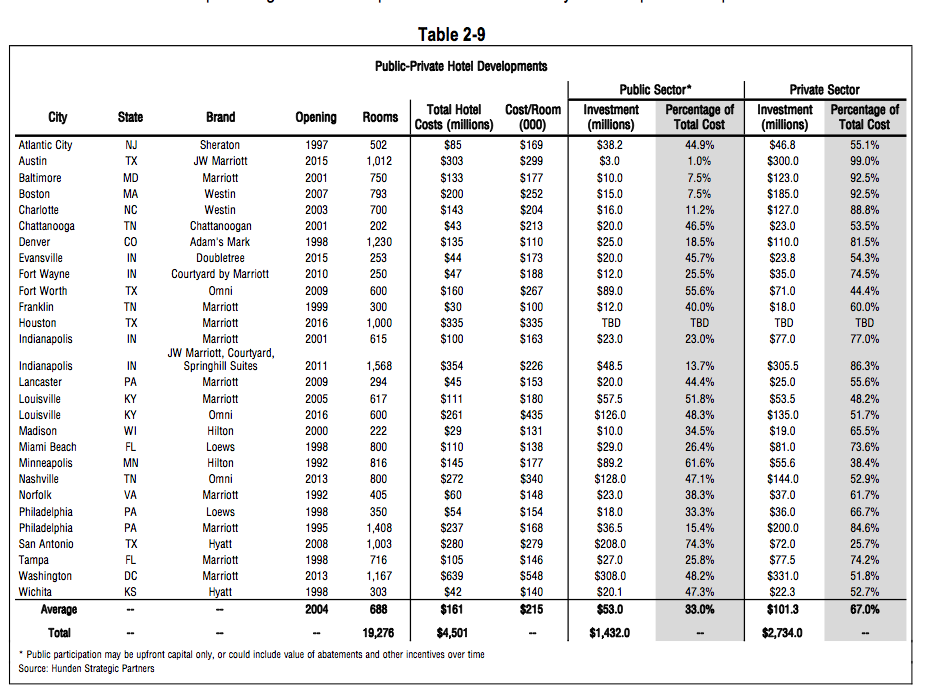

The public cost of the headquarters hotels are now measured in billions.

Cities around the country are throwing scarce public resources into subsidizing headquarters hotels as a way to try and drum up more business for struggling convention centers. According to the report, cities have put more than $1.4 billion in public funds into the construction of almost 20,000 hotel rooms in 28 projects around the country.

Cities are being conned by clearly unrealistic consultant studies into believing that their money-losing convention center, with just a bit more space or a somewhat newer or somewhat larger “headquarters” hotel, can turn things around. But outside of a handful of places like Orlando and Las Vegas — cities that dominate the market for big national conventions — the convention business is, by and large, a municipal money loser. Caveat Emptor!