There’s a growing body of evidence that economic integration—avoiding the separation of rich and poor into distinct neighborhoods—is an important ingredient in promoting widely shared opportunity. The work of Raj Chetty and his colleagues shows that poor kids who grow up in mixed income communities experience far higher rates of economic success than those who live in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty.

We know that one of the principal channels through which this process works is the quality of local schools. Schools in mixed-income neighborhoods tend to have students from both high-income and low-income strata, and benefit from the generally higher levels of parental involvement and resources that higher-income families are able to lavish on schools. Massey and Rothwell have shown that one’s neighbors educational level is nearly half as powerful as one’s own parent’s level of educational attainment in explaining children’s long term economic success, and they hypothesize that much of this effect is transmitted through the school system.

At the same time, the composition and quality of urban schools has been a critical challenge for cities around the country. For decades, as higher income families decamped cities for the suburbs—in part to get access to what were perceived as better schools—urban school districts have faced a triple whammy of declining enrollments, a growing concentration of students from poor families, and declining fiscal resources. The results are chronicled in a new Government Accountability Office report.

GAO compiled data from the National Center for Educational Statistics, and classified schools as low poverty, high poverty, and all other based on the fraction of students in each school eligible for free and reduced-price school lunches. (Low poverty schools were those where no more than 25 percent of students were eligible; high poverty schools had at least 75 percent of students eligible. The data show that in little more than a decade the number of students enrolled in low poverty schools has fallen by half (from 39 percent to 20 percent), while the number of students in high poverty schools has increased from 14 percent to 25 percent. As the GAO report details, students of color are much more likely to attend high poverty schools; 48 percent of black students and 48 percent of Latino students attend high poverty schools, compared to only 8 percent of white students.

Share of K-12 Students Enrolled by Poverty Status of School

| 2000-01 | 2005-06 | 2010-11 | 2013-14 | Change, 2000-01 to 2013-14 | |

| Low Poverty | 39% | 33% | 24% | 20% | -19% |

| All Other | 47% | 51% | 56% | 54% | 8% |

| High Poverty | 14% | 16% | 20% | 25% | 11% |

Source: GAO, K-12 EDUCATION: Better Use of Information Could Help Agencies Identify Disparities and Address Racial Discrimination, April 2016, GAO-16-345.

In the past couple of decades, as we’ve long noted, there’s been a revival in the fortunes of urban centers. In many cities, population growth has been rekindled, particularly by the movement of well-educated young adults into urban centers. But the long-term resilience of this trend depends on whether young adults will stay in cities once they start having children, a question that hinges directly on the quality of urban schools.

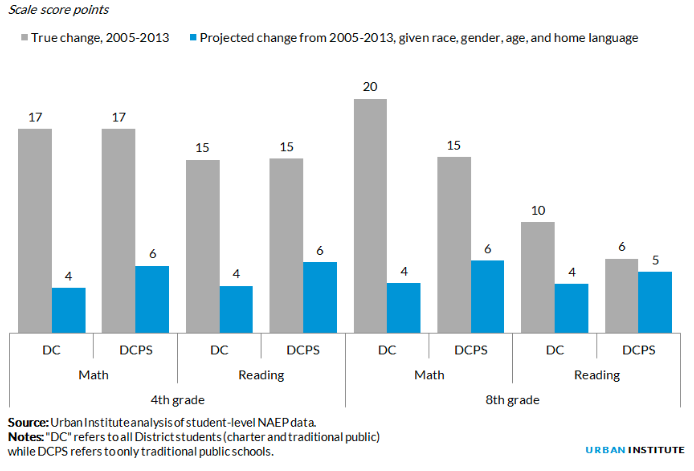

Against this backdrop comes news that test scores in the Washington, DC school system have chalked up some impressive gains in recent years. According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), reading and math scores for fourth and eighth graders have seen significant increases.

As the population of the District of Columbia has changed in recent years, that’s begun to alter the demographic characteristics of the students in DC schools. More kids are from wealthier and whiter families, fewer are from poor families, immigrant households and families of color. But as we’ve written, the growing wealth of urban centers has not yet entirely converted them into the sort of playgrounds for the white and wealthy that is sometimes supposed: it’s still the case that two out of every three school age kids in the District of Columbia are black, and an even higher fraction of public and charter school students. Some have feared that the increase in test scores is solely a result of these demographic changes—that scores are higher simply because different students are taking the tests.

A new analysis from the Urban Institute challenges that view. After controlling for changes in the race and ethnicity of the student body, they find that scores have increased much faster than can be explained by demographic changes. The analysis also concludes that the gains in test scores can’t be explained solely by changes in parental educational levels—one key measure of socioeconomic status. The data show gains in scores in both conventional public schools, and also in charter schools. The Urban Institute findings echo an earlier analysis by District of Columbia’s Office of Revenue Analysis, that shows that adjusting for race and ethnicity does little to change increase in test scores.

While the Urban Institute study confirms that test score increases are real, it doesn’t answer the question of why scores improved. There have been a series of changes enacted in the District in the past decade: new educational management under Michelle Rhee and her successors, a stronger Mayor role in school governance, and increased resources and more widespread adoption of charters.

And while the increase in educational scores isn’t simply a product of the district’s changing population, it could well be that gentrification in the district has a synergistic or interactive effect with these other forces. Education reform measures in the district may be more successful if they’re undertaken with a slightly different mix of students, in schools where a higher fraction of families have the resources to support learning and engage in the schools. They may also be more politically effective in holding the city and schools accountable for results.

While the data gathered so far can’t definitively answer these questions, the noticeable improvement in educational results in the District of Columbia is an encouraging sign for the city’s future growth. It suggests that city schools can improve, and that, in turn, makes the city a more attractive home for young families who might have felt compelled to move to suburbs to get better school quality. And for city students who otherwise might have been isolated in economically segregated, under-performing schools, it means that they have better educational, and in the long run economic opportunities. We’re looking forward to future research that can help measure and sort out these explanations.