One factor trumps all others in determining economic success: Educational attainment

Brookings researchers pile on more evidence of this key fact, and outline strategies for increasing skills.

But remember: talented workers are mobile, so you also have to have a great urban environment to attract and retain smart workers.

Our friends at the Brookings Institution have a new report advising cities on economic development policy. Entitled Talent-Driven Economic Development: A new vision and agenda for regional and state economies, and written by Joseph Parilla and Sifan Liu, the report details a series of strategies that cities can pursue to adapt to the knowledge based economy. As the title suggest, the key to economic success in the 21st century is talent.

This strategic direction will come as no surprise to reader’s of City Observatory, When we first launched our think tank five years ago, we published this commentary, highlighting the role of educational attainment.

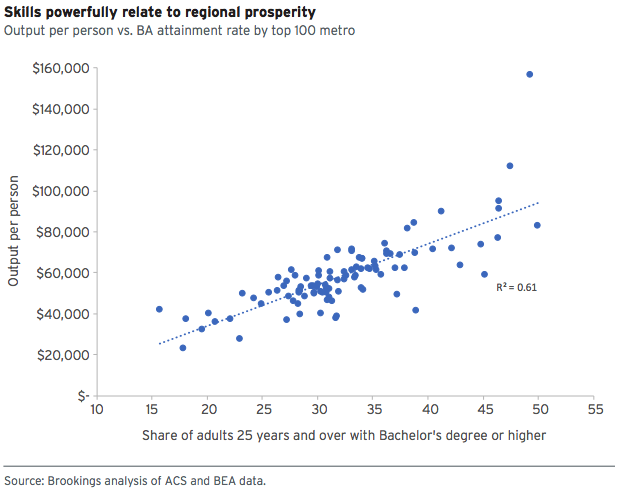

The single most important factor driving urban economic success is the educational attainment of a city’s population. Statistically, educational attainment–summarized by the fraction of the adult population with a four-year college degree–explains roughly 60 percent of the variation in per capita incomes among large U.S. metropolitan areas. No other single factor comes close.

This chart is the first, most important thing to remember about urban economic development in the 21st century: if you want high incomes, you need to have a high level of skills. Cities with poorly educated populations will find it difficult to raise living standards in a world where productivity and pay depend increasingly on knowledge.

The new Brookings report features a strikingly similar chart — although it looks at the connection between a measure of economic productivity (Gross Domestic Product per capita) rather than our preferred measure of income per capita and provides data for the 100 largest metro areas, rather than just those with a million or more population. The data shows that regions with high levels of educational attainment generate more economic output per person: better educated workers are more productive.

The results and the implications are almost exactly the same: Statistically, one can explain about 60 percent of the variation in economic performance amount cities simply by knowing what fraction of the adult population has a four-year degree. That relationship holds regardless of whether we measure economic success in the form of per capita personal income, or the value of output.

As we stressed in our explanation of this relationship, the four-year college attainment rate is a proxy for the overall skill level of the population, the data on college degree attainment are relatively easy to get, even if they are an imperfect and inexact representation of the talent and skills of a local population. And clearly, it isn’t just a four-year degree that matters; cities with highly levels of four-year degree attainment also tend to have fewer high school dropouts, more people with associates degrees and more with graduate degrees. The point is that progress along this educational continuum fuels economic success.

And that’s chiefly where the Brookings report’s recommendations fall: How to move local students further along that continuum. Some of that revolves around continuing formal education (helping high school students reach college, and succeed once they’re there), and also helping and encouraging employers to provide additional training to their entire workforce (and not just those with the highest levels of skill, which tends to be the pattern). These are all plausible elements of a human capital based economic strategy. Parillia and Liu also make the critically important point that there are social spillovers from education: your personal economic prospects are better if you live in a community or region with a high level of educational attainment, regardless of how much education you personally have completed.

Cities have to compete for talented workers by offering great urbanism

The one thing that is conspicuously missing, in our view, is the acknowledgement that people, especially those with high levels of education and skills are highly mobile. It may be necessary and helpful for a city to do a better job of educating its population and promoting lifelong learning, but that will be of little value to the local or regional economy if, once equipped with higher skills, they move elsewhere. As we’ve demonstrated in our studies on the Young and Restless, well-educated young adults are extremely likely to move, and are tending to move to cities with great urban neighborhoods. The upshot is that in addition to fostering more education, cities also need to build the kinds of urban places that will attract and retain talented people.

Increased educational attainment and steadily improving talent should be the centerpiece of any local economic strategy. That will require cities to improve formal learning, buttress lifelong learning and, importantly, build great places.