Covid-19 now disproportionately affects rural America, and is hitting red states harder than blue ones. Rural counties have 14 percent of US population and 21 percent of new Covid-19 cases.

The nation’s largest, densest urban counties now have Covid-19 rates lower than mid-sized and smaller metros and rural areas.

This shift to a largely rural and red state pandemic undercuts the premise for the “urban flight” narrative that’s dominated media coverage.

Reporters: We’re still waiting for the stories about rural Americans decamping to cities (or suburbs) and from red states to blue ones, where they will be safe from the pandemics.

Last month, we highlighted three different analyses of the data on Covid-19 case counts that showed a striking pattern in the spread of the virus, with the nation’s rural areas and red states having much higher levels of new reported cases than urban areas. Now we have another four weeks of data—and they show that rural areas and red states are now even harder hit than the nation’s urban areas and blue states. Indeed economist Jed Kolko and the team at the Daily Yonder have both updated their analyses of the geography of Covid.

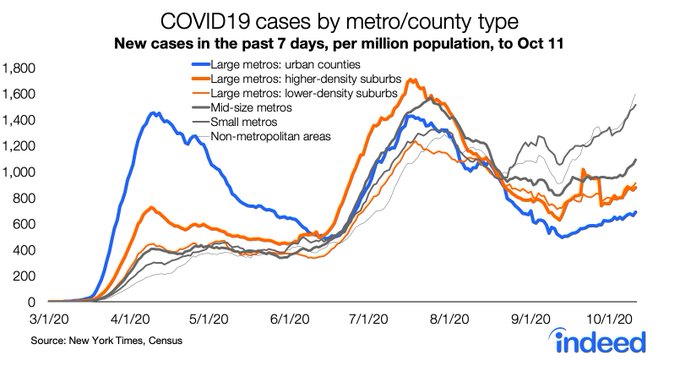

Kolko’s numbers show that the disease continues to worsen in smaller metros and rural areas, and it is the centers of the nation’s most populous metro areas that have been the most successful in suppressing the virus. His chart shows the variation in the number of new cases per million population by metro size.

The lowest rates of new cases are found in the urban counties of large metro areas; meanwhile, the number of new cases in the smallest metro areas and rural towns is far higher, reaching the peaks recorded in April and July. The path of the disease has diverged sharply between urban and rural areas since mid-August, with far worse performance in the most sparsely settled places. Notice the pattern of the blue line, which represents the most urban counties in large metro areas: it’s gone from above average in April, to middle of the pack in July, to the bottom in October, showing that urban areas have made dramatic progress relative to the rest of the nation in managing the pandemic.

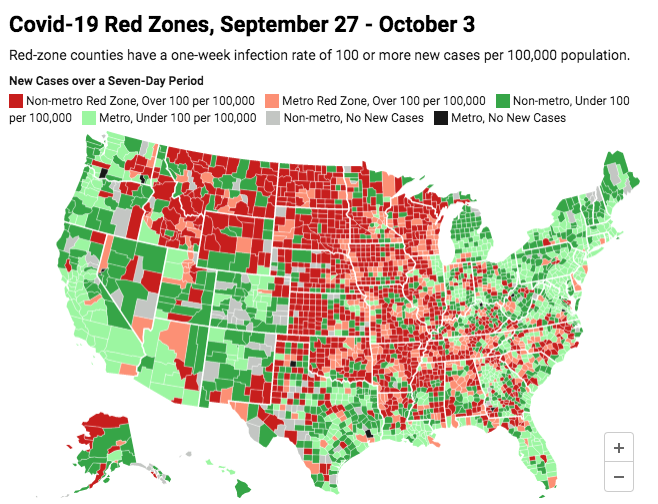

The geographic variation in the pandemic is clearly illustrated by the maps created by our friends at the Daily Yonder. They’ve used the federal government’s red zone classification (a county with more than 100 new cases in a week per 100,000 population) to show where the disease is spreading fastest.

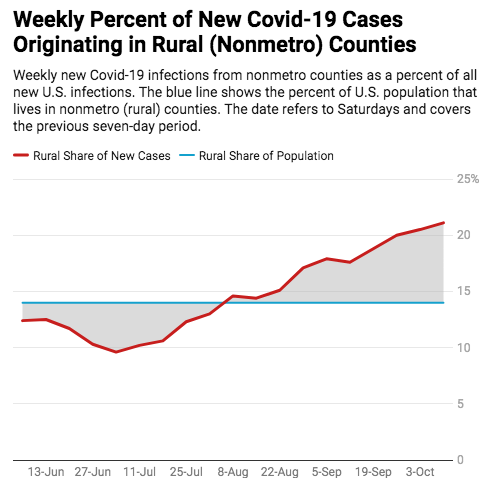

They’ve mapped the places where the current level of new cases is highest: it’s clearly in the heartland of rural America. The worst hit areas stretch in a band of red from the Gulf Coast to the Dakotas. The Covid pandemic is now dramatically worse in rural America: 21 percent of new cases last week were in rural America, compared to just 14 percent of US population; until August, rural areas were under-represented in new cases.

Brookings Institution’s Bill Frey has also been tracking the Coronavirus (again, using a slightly different definition) and comes to very similar conclusions. Frey has also made the obvious connection between red states and red zones. Here’s his chart showing the recent rate of new cases per capita for different sizes of metro areas, split out by whether they’re located in a red state (voted for Trump in 2016), or a blue state (voted for Clinton). In every class of metro and non-metro area, current case rates are higher in red states than blue states.

The implication here seems clear: Places that lean Democratic appear to be much more successful in fighting the spread of the Coronavirus than roughly similar sized places in Republican states. Correlation isn’t causation, of course, but it is striking that more than six months after the seriousness of the pandemic became clear, that some places are doing a far better job of controlling its spread than others.

Where’s the new narrative?

Early on, we saw a veritable journalistic sub-genre of urban flight fiction: everyone was fleeing cities to escape the Coronavirus. Henceforth, the story went, Americans would decamp from crowded, unhealthy cities, to safer suburbs and rural areas. We’ve profiled—and punctured—the median press account several times: some wealthy middle aged professional couple who formerly resided in a big city (usually New York), had tired of the trials of the Coronavirus, and moved to New Jersey, or California. The story was usually punctuated with hand-waving by the local realtor who handled their purchase, crowing over a big uptick in interest from city-dwellers. The trouble of course is that the “urban flight” story isn’t borne out by actual data for real estate markets: in fact, growth in searches for homes and apartments in denser city neighborhoods out-paced those in suburbs and rural areas in the early days of the pandemic, according to Zillow and ApartmentList.

But more to the point, the premise of the “urban flight” story turns out to be flatly wrong: density doesn’t cause or exacerbate the pandemic, and leafy suburbs and bucolic rural communities aren’t immune in any way from the Coronavirus. Now, after more than half a year of experience with the pandemic, and a much clearer understanding of why it spreads, and how to stop it, it’s clear that the disease is dramatically worse in small town and rural America.

So where, we ask, are the journalistic stories about rural residents packing up, Joad-like, and fleeing to cities? We’re just waiting to hear reporters chronicling stories of people moving from rural areas and from Red States to escape the scourge of the Coronavirus. Given the standards of the earlier urban flight stories, this won’t be hard, just find one or two people who are moving from a rural area or red state to a blue city, toss in some quotes from the real estate agent who handled the transaction, and you’ve got your trend. It’s been a month, and we still haven’t seen the stories, which probably tells us more about America’s lingering anti-urban bias than it does about the pandemic or migration trends.