About 2 percent of all car commuters travel 90 minutes to work, same as a decade ago.

We’ve always been clear about our views on mega commuters, those traveling an hour and a half or more to work daily. As we said last year, mega commuting is a non-big, non-growing non-problem. But the loneliness of the long distance commuter is an evergreen topic for journalists: these poor victims of modern life, consigned to spend long periods of times in their cars, isolated from family and friends.

The latest installment in this long-running saga comes courtesy of Curbed. In an article entitled “Supercommuters, skyrocketing commutes, and America’s affordable housing crisis,” Patrick Sisson various scary sounding data points about the increase in the number of people traveling more than 90 minutes to work each day. (Never mind that the increases reported since 2010 largely reflect the effects of a growing economy; the number of people commuting increased by 11 million between 2010 and 2015. There are obligatory quotes from the Texas Transportation Institute’s researchers–who are always good for a statistic laced lamentation of traffic problems (never mind that the numbers are wildly exaggerated). Sisson’s story draws heavily on a recent data analysis by the Pew Charitable Trusts Stateline in a story titled: “In Most States, a Spike in ‘Super Commuting.‘”

Don’t get us wrong: there’s nothing pleasant about long commutes. Quite the opposite, we (and most people) recognize that they’re toxic. But let’s put a few facts in order.

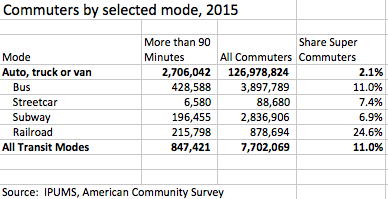

Very few people have long commutes. Among car commuters in the US, only about 2 percent of all commuters have a commute of ninety minutes or more. Ninety-eight percent of us manage to get to work in less time.

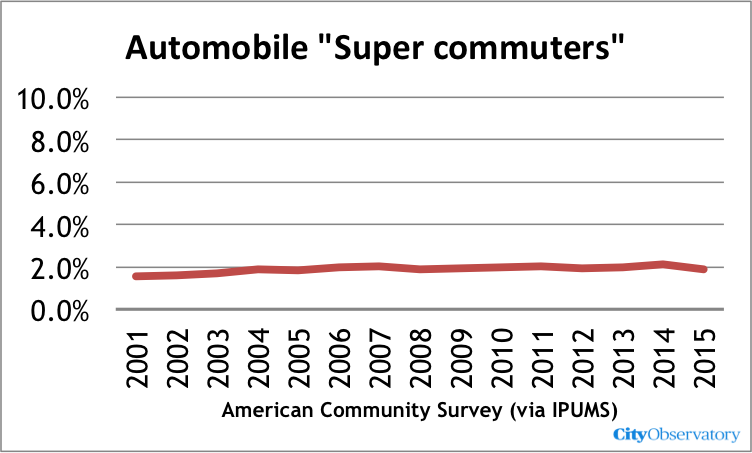

Contrary to what you may have heard, long duration commutes are not growing as a share of all commuting. We’ve dug up 15 years worth of Census surveys on car commuting behavior from the data compiled by the Integrated Public Use MicroSample Project (IPUMS). These data let us slice and dice commuting patterns by mode and by year. Here’s a chart showing the share of automobile commuters who reported traveling 90 minutes or more each year between 2001 and 2015 (the latest year for the American Community Survey).

There was a brief period of growth of commutes, from about 1.6 percent in 2001-02 to about 2.0 percent in 2006. Then a slight decline, and then an uptick back to 2.1 percent in 2014. The record of the last decade or so hardly qualifies as “skyrocketing.” It’s pretty much flat.

If we are concerned about super commuters, there’s a good argument to be made that our attention ought to be directed to those folks who travel via public transit. The American Community Survey reports on usual mode of travel to work, so we’ve estimated separately the number (and share) of super commuters among those who travel to work by bus, streetcar, subway or railroad. While just 2 percent of car commuters endure long commutes, more than 10 percent of all these transit commuters have long commutes. Statistically, transit riders are five times as likely to have super commutes than car drivers. So, if we view this “problem” from a transportation perspective, maybe we should be talking about improving the speed and coverage of transit systems.

But its a fair question to ask whether those with long commutes are really the helpless victims they’re portrayed to be in these stories. We know from abundant anecdotes–usually related in the article about the plight of the super commuter–that they’ve chosen to live in some neighborhood far removed from their place of work because it offered them a bigger house, a larger yard, better schools, or simply lower prices than housing that is less than ninety minutes to work. In a very real sense, those who choose longer commutes are rewarded in terms of these amenities. A long commute is essentially “sweat equity,” buying more real estate not with cash received in a paycheck, but by putting in more time behind the wheel to get what you want. Sisson acknowledges as much in his article, quoting Texas Transportation Institute’s Phil Lasley:

Homeowners are now being priced out of many U.S. markets, he says, and are willing to sacrifice transportation time for the neighborhood or lifestyle they want. When it comes down to making a decision, most sacrifice a shorter drive for a lawn, marble countertops, and a good school district.

The recent blip in super commuting in 2015 tends to confirm this sweat equity story. In mid-2014, gas prices fell by about 40 percent, effectively lowering the cost of commuting. The number of car super commuters jumped about 8.9 percent in 2015 over 2014, compared to just an 4.1 percent increase in the previous year.

In the end, the super commuting story tells us more about housing and personal preferences than it does about transportation and public policy. Some people, maybe as many as 2 percent of us, will want to live some place that requires a 90 minute commute to a job (at least for a while in our lifetime). For those people who truly can’t afford any housing closer to their jobs (as opposed to those who are willing to trade off a longer commute for better amenities), its a message that we need to build a range of housing types in all parts of a metro area, and be sure that housing supply expands in line with housing demand.