The Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) has proposed a $1.9 billion freeway widening project for Portland’s Rose Quarter. The agency proposes to cover a portion of the freeway in what it calls “restorative justice” for the Albina neighborhood, that was decimated by decades of earlier ODOT highway building.

But ODOT claims it can’t spend highway money to repair the damage its projects have done—and continue to do—to the historically Black Albina neighborhood. That’s a clear misreading of federal law and policy, which imposes a substantial burden on ODOT to identify and mitigate the damage—past, present and future—from its highway projects.

Rhetorical contrition isn’t enough. Simply acknowledging the damage that its previous projects have done to the Albina neighborhood doesn’t comply with the law: the Oregon Department of Transportation has a legal obligation to mitigate the effect of its past discriminatory practices.

Federal regulations both allow and require the mitigation of negative impacts caused by highway projects, including impacts on neighborhoods and housing losses. Several federal laws and policies mandate identifying and mitigating adverse effects on communities, including social and economic impacts on communities, not just impacts on the natural environment:

- The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) requires assessing adverse impacts and mitigating them, including impacts on the community environment through restoration or providing substitute resources.

- The U.S. Department of Transportation’s Environmental Justice policy requires addressing and mitigating the cumulative negative impacts of transportation projects on community cohesion and economic vitality.

- Title VI of the Civil Rights Act requires recipients of federal funds like ODOT to take affirmative action to overcome the discriminatory effects of previous highway projects.

- The new Reconnecting Communities program allows funds to be used for mitigating impacts identified through the NEPA process.

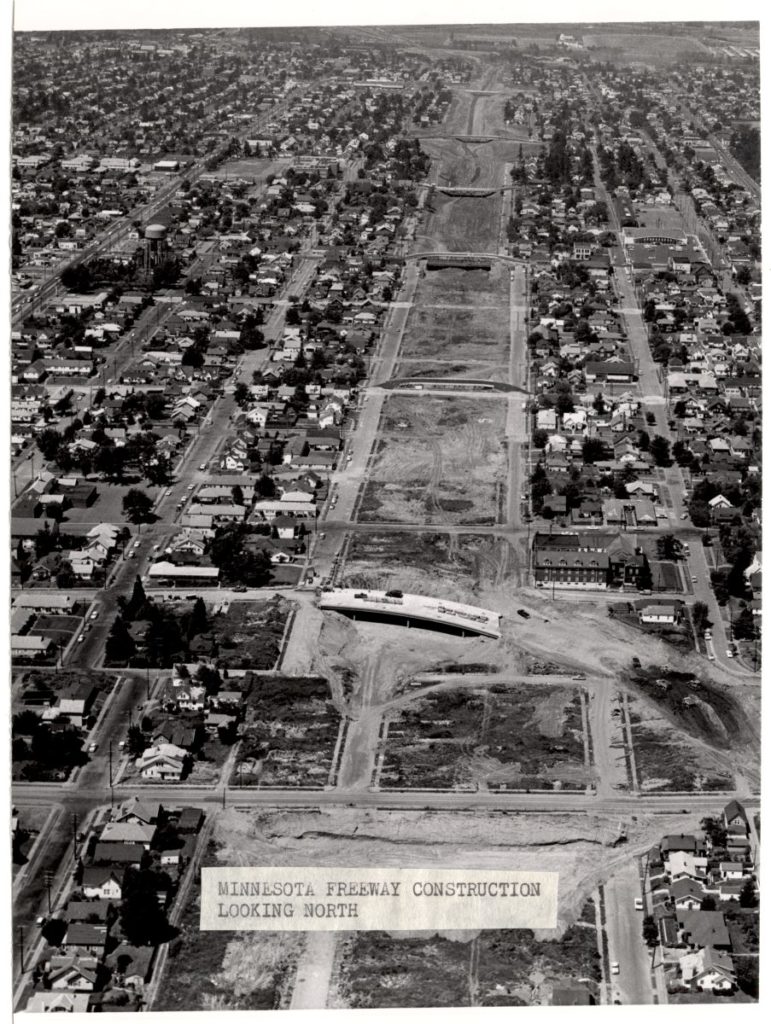

These regulations authorize and require the Oregon Department of Transportation to spend funds repairing the damage its past highway projects have done to the Albina neighborhood in Portland. ODOT’s own Environmental Assessment acknowledges demolishing 450 homes in Albina for highways like I-5, leading to a population decline from over 14,000 in 1950 to around 4,000 in 1980.

However, ODOT has falsely claimed it cannot spend highway funds on mitigation efforts, whether they involve building housing to replace demolished units, or even the added cost of strengthening proposed highway covers to support anything other than streets. There are many examples of how federal highway funds are routinely used for mitigating a wide range of impacts, including:

- Restoring wetlands, fish habitats, and building sound walls to reduce highway noise pollution

- Off-site improvements like paying for a new jail when the I-205 route impacted the existing facility

- Funding community development projects in the historically white Northwest Portland neighborhood impacted by I-405, while not doing so for Albina

Nationally, there are many examples of state DOTs using federal highway funds specifically to build new affordable housing to mitigate the impacts of highway projects:

- Kentucky used funds to establish a community land trust for up to 100 homes impacted by a highway widening project through a Black neighborhood.

- The Texas DOT allocated $27 million for building affordable housing impacted by the I-45 expansion in Houston.

- Nevada DOT provided funds and land for affordable housing replacement due to impacts from highway work in Reno.

using highway funds to restore housing lost to highways in Albina would achieve the “restorative justice” that ODOT claims to support. The I-5 Rose Quarter’s own public involvement efforts have found that the community has identified affordable housing as the top priority based on ODOT’s own public outreach.

Federal regulations give ODOT the ability and responsibility to use highway funds to mitigate past harms to Albina through efforts like rebuilding demolished housing units. It provides examples of how this approach has been implemented elsewhere as evidence that ODOT can and should take similar measures.

City Observatory has prepared a detailed memorandum documenting each of these laws and policies, and illustrating examples of how highway funds have been used to pay to mitigate the social and enviornmental effects of present and past freeway construction. It is available here:

[pdf-embedder url=”https://cityobservatory.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Mitigation_Memo.pdf”]