Starting this spring, motorists will pay a $2 toll to drive Oregon’s historical Columbia River Gorge Highway.

Instead of widening the road, ODOT will use pricing to limit demand

This shows Oregon can quickly implement road pricing on existing roads under current law: No EIS, No equity analysis

If you can do it there, why not anywhere? It’s up to you ODOT.

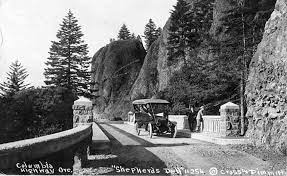

The Columbia River Gorge, just east of Portland, is one of the nation’s scenic wonders. It was formed where the Columbia River cut a path through the volcanic Cascade Mountain Range, and consists of 50 miles of spectacular river views framed by soaring bluffs, green forests and snow-capped peaks. It’s also home to one of the nation’s oldest and most scenic highways, the Columbia Gorge Highway, built in between 1913 and 1922. It was a kind of engineering marvel of its time, crafting and sometimes carving a winding two-lane roadway along the river and into the cliffs of the Gorge.

In the 1960s the old highway was fully replaced by the construction of Interstate 84, but the old road has been maintained and in places restored because of its scenic beauty, and direct access to waterfalls and hiking trails. Less than an hour from Portland, it’s a major tourist and recreational site; Multnomah Falls is the state’s most-visited tourist destination. And that’s become a problem.

On any summer day, or any (somewhat dry) weekend, you’ll find visitors flocking by the thousands to drive the old scenic highway, particularly the stretch between Vista House and Multnomah Falls, which offers a series of postcard views. (This stretch of roadway is also routinely used for filming car commercials).

In recent years, however, traffic has overwhelmed the old highway. The road itself is narrow and winding, and there’s little parking at the parks, waterfalls and trailheads. With great regularity, the highway itself has been jammed, and cars are stopped and idling in front of Multnomah Falls. The traffic is both unsafe and also mars the natural beauty of the location.

Into this fray has stepped the Oregon Department of Transportation. Thankfully, they’re not doing what they usually do, which is proposing to widen the roadway to accommodate even more traffic. Instead, for the first time, they’re implementing a permit system to ration the flow of cars on the old highway to levels that it can accomodate without destroying the experience for those seeking to see one of Oregon’s most beautiful spots.

Starting the week before Memorial Day, and until Labor Day, you’ll need to buy a permit in order to travel on the waterfall-dotted portion of the Columbia River Highway. As Oregon Public Broadcasting reports, this will be a “peak hour” pricing program:

The permit will be required for the approximately 14-mile stretch between Vista House and Ainsworth State Park from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. ODOT is still deciding how many permits to allow per day, as the permits do not guarantee parking.

Let’s be clear: What they’re doing is taking an existing road, and they’re tolling it: imposing limits on how many vehicles can use it so that it works better. This is a huge policy breakthrough for a department that has never seriously done anything to moderate traffic demand. (It’s strongest effort to date has been funding for half-hearted public relations campaigns that gently imply that people might want to drive less).

ODOT is planning to charge $2.00 for these permits. This will mostly just recoup their direct administrative costs. But if they do it right, it won’t take much of a fee to bring traffic levels down. Just requiring a permit will force people to plan ahead, and will keep people from overwhelming the Gorge on a sunny early spring weekend day. And the fees levied for these permits could be used to expand ODOT’s existing bus service “Columbia Gorge Express” which provides rides to key Gorge destinations. Getting more visitors on buses will reduce traffic and pollution in the Gorge.

Crossing the Rubicon: The Gorge Highway toll shows ODOT can implement road pricing quickly if it wants to.

For more than a decade, ODOT has been dragging its bureaucratic feet in implementing road pricing. The 2009 Legislature instructed the agency to run a test of pricing in the Portland area; instead the agency counted a special game-day street parking surcharge near the Timber’s soccer stadium as its “pricing” plan. The 2017 Legislature directed ODOT to implement pricing on Portland’s two major freeways (I-5 and I-205); so far, they’re still just working on the planning.

The agency has argued that it has to undertake extensive environmental reviews, that it must consult widely about the potential equity implications of pricing, and that it would be unprecedented (and somehow unfair) to extend pricing to an existing roadway. All those concerns have gone out the window in its announced plans for the Columbia River Gorge.

In ancient Rome, the Rubicon was the boundary which the Roman legions (and their ambitious commanders) were forbidden to cross. When Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon River it led to the political upheaval that replaced the Republic with his empire. When it comes to road pricing, The Columbia River Gorge could serve as Oregon’s road pricing Rubicon. We could harness the power of pricing to tailor demand for the transportation system to the levels that are compatible with our livability and environmental objectives. Notice how Oregon DOT spokesman Don Hamilton explains the rationale for the Gorge highway tolling project:

“The Gorge is really Oregon’s crown jewel. Everybody in Oregon and in the region is very proud of the Columbia River Gorge,” Hamilton said. “We’re trying to continue to make this accessible and trying to ease the crowds a little bit to make sure that we can still have access to the Gorge and make sure it doesn’t get overrun.”

What ODOT needs to do next is apply this same reasoning to the rest of the overcrowded bits of its transportation system: i.e. urban freeways in Portland. Hamilton’s reasoning applies with even greater force to congested freeways. To paraphrase:

“We’re trying to make this accessible and ease the crowds a little bit so we can still have access to the city and make sure it doesn’t get overrun.”

If roads are jammed to capacity, the solution is not an expensive, disruptive and environmentally damaging expansion, it’s putting in place some kind of pricing or permitting system that limits the volume of cars and trucks on the roadway to levels it can handle without becoming jammed and making the roadway worse for everyone.

There’s an important historical parallel. The construction of the Columbia Gorge Highway a century ago showed the limits of the old horse-and-buggy system of road finance in Oregon, and directly led to Oregon’s first-in-the-nation adoption of a gasoline tax in 1919 to finance a statewide system of roadways. At the time, the gas tax was a huge innovation in public finance. In the 21st Century, it’s time to implement a new way of paying for roads that works better, is fairer, and minimizes congestion and environmental harm. Extending ODOT’s Gorge highway pricing system to the rest of the states roads should be next.