The $7.5 billion Interstate Bridge Replacement Project’s two-decade old “Purpose and Need” statement is simply wrong, and provides an invalid basis for the project’s required Environmental Impact Statement.

Contrary to claims by project proponents, the “Purpose and Need” statement isn’t chiseled in stone, rather it is required to be evolve to reflect reality and better information. Yet IBR is relying on a 2005 purpose and need statement that rests on exaggerated traffic forecasts that have been proven wrong.

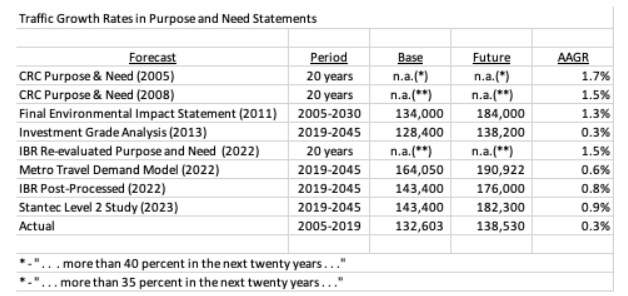

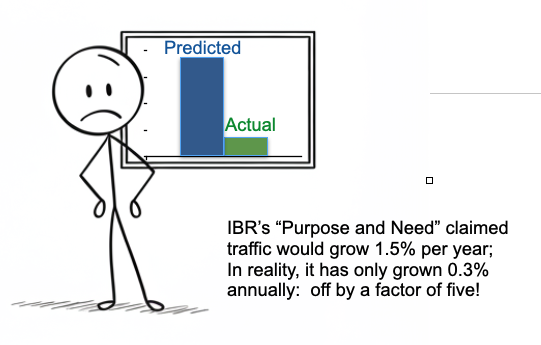

The IBR’s 2005 Purpose and Need Statement (still forms the basis for the 2024 SDEIS) claimed the I-5 needed to accommodate 1.7 percent more vehicles each year. In reality, traffic growth has been less than a fifth of that amount, 0.3 percent from 2005 to 2019.

For decades, highway builders have been pushing a “predict and provide” paradigm, pretending that we needed to plan for an ever-increasing flood of vehicle traffic, and threatening gridlock if highways weren’t expanded. But these self-serving predictions have consistently proven wrong.

Law and policy require that the “Purpose and Need” statement be reasonable, and not drawn so narrowly as to exclude alternatives, and that the statement evolve over time as conditions change. But IBR is using, nearly unchanged, a two-decade old statement that falsely claims that I-5 must accommodate ever greater traffic.

IBR officials are clinging to an out-dated and simply incorrect purpose and need statement to inflate the size of the project, and to rule out lower cost alternatives with fewer environmental impacts, in violation of NEPA.

In the world of mega-infrastructure projects, few things are more important than accurately defining the problem you’re trying to solve. For Portland’s proposed Interstate Bridge Replacement project, that definition comes in the form of a “Purpose and Need” statement – a crucial document required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). This statement isn’t just bureaucratic paperwork – it’s the legal foundation that shapes the entire environmental review process. Under NEPA, the Purpose and Need statement determines which alternatives must be studied and which can be eliminated from consideration. It essentially sets the parameters for what counts as a potential solution.

The current Interstate Bridge Replacement (IBR) project is recycling, wholesale, a Purpose and Need statement originally drafted in 2006 for its predecessor, the Columbia River Crossing. That document’s central claim – that daily traffic demand would grow by more than 35 percent over 20 years – has proven wildly inaccurate. Rather than growing at the predicted rate of 1.7 percent annually (later revised to 1.5 percent), actual traffic on the I-5 bridge has grown at just 0.3 percent per year from 2005 through 2019, and an even lower 0.1 percent rate from 2005 to 2023.

This isn’t just a technical detail – it’s fundamental to the entire environmental review process. Under NEPA, agencies must rigorously explore and objectively evaluate all reasonable alternatives that could meet the project’s purpose and need. By vastly overstating future traffic growth in its “Purpose and Need” statement, the project artificially constrains the range of possible solutions, effectively mandating an oversized project while eliminating potentially more modest and less environmentally damaging alternatives from consideration. In essence, the exaggerated traffic projections become a self-fulfilling prophecy – by claiming we need infrastructure sized for phantom traffic growth, the project excludes more modest solutions from even being studied.

The Purpose and Need Statement must reasonable, not narrow

This matters because federal environmental law requires that projects consider a reasonable range of alternatives. As the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals noted in a key decision, it is “contrary to NEPA for agencies to contrive a purpose so slender as to define competing ‘reasonable alternatives’ out of consideration (and even out of existence).” Yet that’s exactly what appears to be happening here – by defining the project’s “need” as accommodating 35 percent more vehicles in twenty years, when all evidence suggests we won’t see anywhere near that growth, the IBR effectively eliminates smaller-scale alternatives from consideration.

The Purpose and Need Statement should evolve—but hasn’t

The federal Department of Transportation’s own guidance recognizes that Purpose and Need statements should evolve as new information becomes available. Their NEPA implementation guidelines explicitly state that “the purpose and need section of the project may, and probably should, evolve as information is developed and more is learned about the project and the corridor.” Yet despite having nearly two decades of actual traffic data that contradicts their original assumptions, the IBR team has chosen to simply copy and paste the old statement rather than update it to reflect reality.

And the old purpose and need statement has been proven hopelessly wrong. In 2005, the Purpose and Need Statement claimed traffic would increase “more than 40 percent in the next twenty years” implying an annual growth rate of traffic of 1.7 percent per year. The 2008 Purpose and Need Statement downgraded that to 1.5 percent per year, and the “Re-evaluated” purpose and need statement adopted in 2022 made exactly the same claim. Now, with the passage of time, we know that actual traffic growth, even in the “normal” times prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, was less than one-fifth as fast–about 0.3 percent per year. And none of the forecasts that have been done since the original purpose and need statement confirm its extremely high growth rate.

This isn’t just about traffic forecasts – it’s about fiscal responsibility and environmental stewardship. Building infrastructure based on phantom traffic growth risks saddling the region with excessive debt for oversized facilities we don’t need, while potentially causing unnecessary environmental damage. The Purpose and Need statement’s exaggerated growth projections are being used to justify a massive project when more modest alternatives might better serve the region’s actual needs.

The implications are serious. If the Purpose and Need statement artificially eliminates reasonable alternatives from consideration by overstating future traffic growth, the entire environmental review process is legally suspect. Courts have consistently held that agencies cannot define project purposes so narrowly that they eliminate reasonable alternatives from consideration. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which covers Oregon and Washington, has explicitly stated that “an agency cannot define its objectives in unreasonably narrow terms.” But that’s exactly what the IBR project has done: called for a project that accommodates 1.5 percent annual traffic growth, even though traffic is growing one-fifth as fast.

The solution is straightforward: update the Purpose and Need statement to reflect actual traffic trends and realistic projections. This would allow for consideration of a broader range of alternatives, potentially including more modest solutions that might better match the region’s real needs while reducing environmental impacts and costs. Instead of being locked into a massive project designed for phantom traffic, the region could explore solutions scaled to actual demand.

The Interstate Bridge Replacement project is potentially the region’s largest-ever infrastructure investment. Getting it right matters. But you can’t get the right answer if you start with the wrong question. By clinging to demonstrably incorrect traffic projections in its Purpose and Need statement, the project risks building tomorrow’s infrastructure based on yesterday’s flawed assumptions. Before proceeding further, project leaders should revise their Purpose and Need statement to reflect reality, not highway engineer fantasy.