Fundamentally, the nation’s housing affordability problems are due to demand outpacing supply: there’s more demand to live in some cities–and especially in great urban neighborhoods–than can be met from the current supply of housing, especially apartments. As demand surges ahead of supply, rents get bid up, which is the most visible manifestation of the affordability problem. But higher rents are also a signal to developers that they ought to build more housing, and when and where local zoning allows it, they do. Over the past two years, rising rents have produced a surge of new apartment construction, and there’s growing evidence–in some markets, and at least for the short-term–these increments to supply are moderating the rate of rent hikes.

There’s no denying that rents in the US have escalated over the past several years. Overall rents are up 4.6 percent in the past year, and the national rental vacancy rate has plunged from more than 10 percent to about 7 percent, signaling that their are relatively more tenants bidding for every available apartment. As a result the share of households spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing has increased.

Nothing, it seems, is more infuriating to those caught in a market of steady rent hikes that being lectured by some economist that what is needed to resolve the problem is an increase in supply. Nice to know, but that’s not going to pay the rent any time soon. But just as after a long winter there are some early signs of spring, there are a few hopeful indicators from housing markets that the long promised relief from increased supply is starting to show up, at least in a small way. Today we look at recent market reports, national and local, that provide some evidence that the predicted market forces are at work.

First, in New York, home to some of the most expensive real estate in the nation, there’s growing evidence that rent inflation is easing, at least at the high end of the rental market. According to Bloomberg, the inventory of vacant, for-rent apartments in New York has increased by between 20 and 30 percent in the past year. As a result, nearly a quarter of all apartments listed for rent in Manhattan in October included landlord-offered incentives or concessions, the highest level recorded in the past decade. Figuring in the value of these concessions, brokers estimate that median rents in Manhattan fell by about one percent, year-over-year. Even in Brooklyn, where rents have been rising rapidly, the number of for-rent units with landlord concessions increased from 8 percent to 12 percent in the past few months.

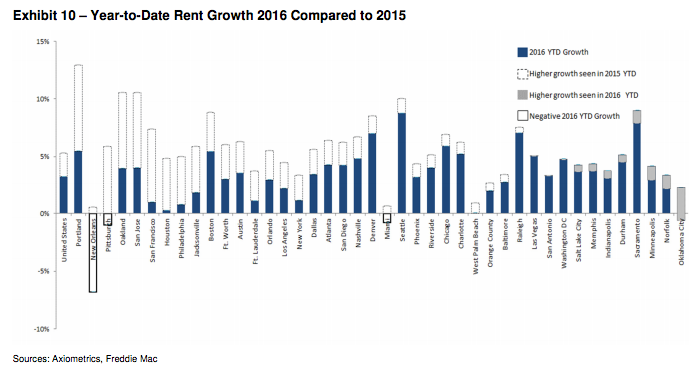

The same pattern observed in New York is starting to play out around the country. Market analyses by Freddie Mac (the federal mortgage agency) and by real estate analytics firm Axiometrics suggest that in most metro areas around the country, rent increases are moderating, and that this trend is likely to continue in the near future. Comparing first half 2016 rent growth with the same period in 2015, the data show that rent increases are slowing in most markets. In 28 of the markets shown below, rent increases are slower now than in the previous year; in three markets they are about the same, and in eight markets, rents are accelerating. (In the chart, white outlined bars indicate 2015 rent growth, and blue bars represent 2016 rent growth). Rent increases are significantly lower in 2016 than the previous year in Portland, Oakland, San Jose, Boston, Austin, Houston and Philadelphia, to name a few.

Looking forward, Axiometrics predicts that for the next couple of years, rent increases will moderate. Rents increased about 4.6 percent nationally in 2015, and are expected to rise a further 3.4 percent in 2016. But the outlook for 2017 is for an increase of 2.1 percent.

While national trends provide a helpful background, like politics, all housing is local. In an important sense, there really is no “national” apartment marketplace: apartments built in Cheyenne Wyoming really aren’t good substitutes for apartments in New York. While there are broad national trends, the trajectory of supply and demand can play out differently in different local markets. But even in San Francisco, where rental inflation has been severe, and where its famously difficult to build new housing, there’s an indication that added supply is also moderating rent increases: according to Freddie Mac, rents there have increased only about 0.9 percent over the past year, just a fraction of the increases being recorded a year ago. And while much of this is attributable to rising supply, at least some of the problem is what the analysts call “renter fatigue”–renters simply can’t afford higher rates than now being charged.

Nobody’s predicting a glut of unoccupied apartments that will push rents down. But slowly, and inexorably, the supply of housing is catching up to the demand, both in the aggregate and in the specific places where demand has grown most rapidly. It’s a reminder that if policy enables housing supply to expand, relief from higher rents can be delivered through the market.