Just a few months ago we were being told—erroneously, in our view–that the McMansion was making a big comeback. Then, last week, there were a wave of stories lamenting the declining value of McMansions. Bloomberg published: “McMansions define ugly in a new way: They’re a bad investment –Shoddy construction, ostentatious design—and low resale values.” The Chicago Tribune chimed in “The McMansion’s day has come and gone.” Whither are these monster homes headed?

First, as we’ve noted, its problematic to draw conclusions about the state of the McMansion business by looking at the share of newly built homes 4,000 feet or larger (one of the standard definitions of a McMansion). The problem is that in weak housing markets (such as what we’ve been experiencing for the better part of a decade in the wake of the collapse of the housing bubble) the demand for small homes falls far more than the demand for large, expensive ones. So the share of big homes increases (as does the measured median size of new homes). And indeed, that’s exactly what happened post–2007: the number of new smaller homes fell by 60 percent, while the number of new McMansions fell by only 43 percent, so the big homes were a bigger share (of a much smaller housing market). Several otherwise quite numerate reports gullibly treated this increased market share as evidence of a rebound in the McMansion market; it isn’t.

We proposed a McMansion-per-millionaire measure as a better way of gauging the demand for these structures, and showed that the ratio of big new houses to multi-millionaire households did indeed peak in 2002, and has failed to recover since. We built about 16 McMansion per 1,000 multi-millionaires in 2002, and only about 5 in 2014.

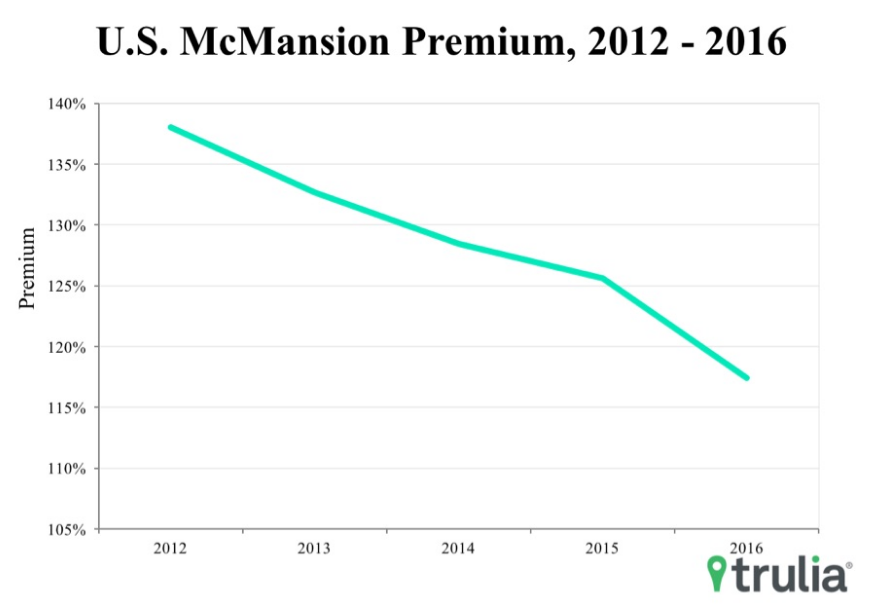

Another way of assessing the market demand for behemoth homes is by looking at the prices they command in the market. What triggered these recent downbeat stories about McMansions was an analysis entitled “Are McMansions Falling out of favor” by Trulia’s Ralph McLaughlin, looking at the comparative price trajectories of 3,000 to 5,000 square foot homes built between 2001 and 2007 and all other homes in each metropolitan area. McLaughlin found that since 2012, the premium that buyers paid for these big houses fell pretty sharply in most major metropolitan markets around the country. Overall, the big house premium fell from about 137 percent in 2012 to 118 percent this year.

In a way, this shouldn’t be too surprising. Part of the luster of a McMansion is not just its size, but its newness. Like new cars, McMansions may have their highest value when they leave the showroom (or the “Street of Dreams” moves on). According to the Chicago Tribune’s reporting on this story, apparently today’s McMansion buyer wants dark floors, gray walls, and white kitchen cabinets, very different materials and color schemes than last decade’s big houses. As they age, we would expect all vintage 2005 houses to depreciate, relative to the market. This gradual decline in value is essential to the process of filtering–housing becomes more affordable as it ages. (And at some point, usually many decades later, when the surviving old homes acquire the cachet of “historical” — they may begin appreciating again, relative to the rest of the housing stock).

There’s another factor working against the McMansion, in our view. In general, these large homes have generally been built on the periphery of the metropolitan area, in suburban or exurban greenfields. As we’ve shown, the growing demand for walkability and urban amenities has meant an increase in prices for more central housing relative to more distant locations. Its likely that this trend is also hastening the erosion of the big house premium.

Finally, there is a financial angle here, too. McMansions were at the apex of the housing price appreciation frenzy of the bubble years. You took the sizable appreciation in your previous house, and rolled it over into an even larger house–hoping to reap further gains when it appreciated. The move-up and trade-up demand that fueled McMansion demand has mostly evaporated. Despite gains in recent months, nominal home values in most markets haven’t recovered to pre-recession levels, and adjusted for inflation, many home owners have yet to see a gain on their real estate investment. According to Zillow, the effective negative equity rate (homeowners who have less than 20 percent equity in their homes) was 35 percent.

There will always be people with more money than taste, so there will always be a market for McMansions (or whatever fashion they might evolve into next). But many of the market factors that combined to boost their fortunes a decade ago have changed. Consumers now know that home prices won’t increase without fail and the interest in ex-urban living has waned. Homeownership overall is down, and much of the growth in homeownership will be among older adults (who probably won’t be up-sizing).