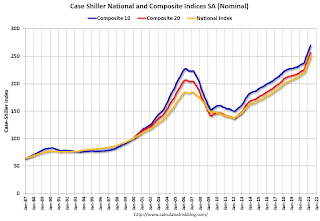

The decline in interest rates in 2020 is a huge factor in explaining the recent surge in home prices.

Population growth, a key driver of housing demand, actually slowed dramatically in the past year.

The current surge in home prices may be a short-term phenomenon.

We’re constantly being told that the housing market is hot, and that the US is facing a housing shortage. There’s no denying that home prices have risen sharply in the past year. The broad-based S&P Core-Logic Case-Shiller index records that the average home price has jumped 14.6 percent in the past year, the fastest increase in three decades (a period that includes the housing bubble of the mid-aughts.

Since most buyers finance their homes with long-term mortgages (plus equity from a current home, if they own one), mortgage interest rates have a profound effect on how much people can afford to pay for housing. When mortgage rates go down, a family can afford to borrow a larger amount of money for any given level of monthly payments they can afford. Since the Covid-19 recession, interest rates, including mortgage interest rates have fallen sharply.

Here’s the typical rate on a 30-year fixed residential mortgage. For the past two years, mortgage rates have been declining, and since the start of the Covid-19 recession, have plummeted to the lowest levels seen in decades.

On January 2, 2020, the average mortgage rate was about 3.7 percent. Just a year later, on January 7 of 2021, the interest rate stood a full percentage point (100 basis points in financial speak) lower, at just about 2.7 percent. That change makes a big difference to how much homes people can afford based on their income.

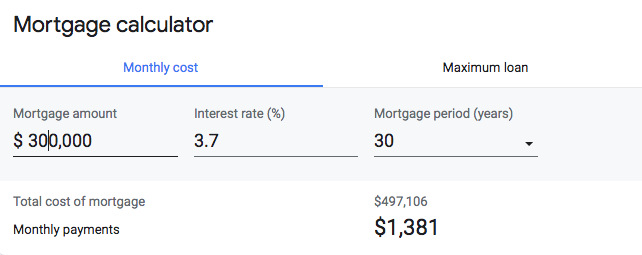

For example, if you were financing a $300,000 mortgage in 2020 at 3.7 percent, your monthly payments would be about 1,380. Here’s a mortgage calculator.

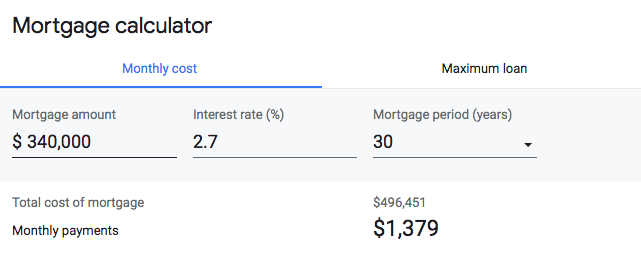

But a year later, in 2021, if you could still afford a $1,380 monthly payment, at the new lower 2.7 percent interest rate, you would now be able to swing a $340,000 mortgage.

That $40,000 increase works out to a 13.3 percent increase in the amount you could borrow, roughly in the same ballpark as the increase in home prices over the past year. (Our simple calculation here overlooks some important details, such as needing a larger down payment for a bigger mortgage, but between government stimulus payments and big reductions in household outlays for travel, entertainment, services caused by Covid restrictions, many households saw big gains in savings during the pandemic).

It’s not population growth

Historically, one of the biggest and most easily predictable drivers of housing markets is population growth. But thanks to direct and indirect effects of the pandemic, national population growth has fallen dramatically. Economist Tom Lawler estimates 2020 population growth fell to 0.22 percent from a 21st Century average of about 0.72 percent. That decline is due both to an increased death rate and subdued international in-migration.

Housing markets are big and complex, and there are many reasons why prices have risen so sharply in the past year. But clearly one of the big factors has been the declining cost of borrowing. Going forward the impetus to home price inflation from the recent decline in interest rates should wane (assuming mortgage interest rates don’t continue to decline at the same pace in the next year or so). If the decline in mortgage rates is largely over, stable or increasing mortgage interest rates should actually help dampen future home price increases.

But as we all learned in the housing bubble, home price movements can become disconnected from fundamentals, and be driven by expectations of future increases. One of the troubles with housing is that homeowners are in many respects speculators, and most buyers are purchasing a new home based in part on the growth in value of a previous home. The current dramatic spike in home prices seems to be propelled by some short term factors, most notably the decline in interest rates. We’ll all want to watch closely to see what happens in the months ahead.