Single-family zoning, a policy that bans apartments, is widespread in Los Angeles County. The median city bans apartments on 80% of its land for housing.

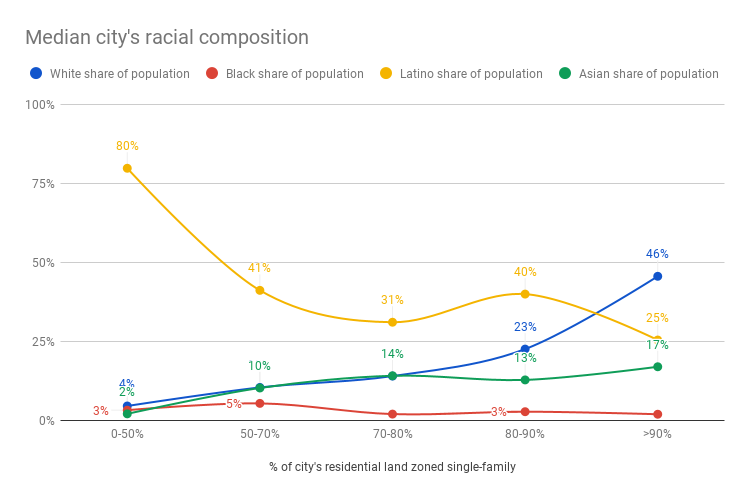

Cities with more widespread single-family zoning have higher white and Asian population shares, and lower Black and Latino population shares.

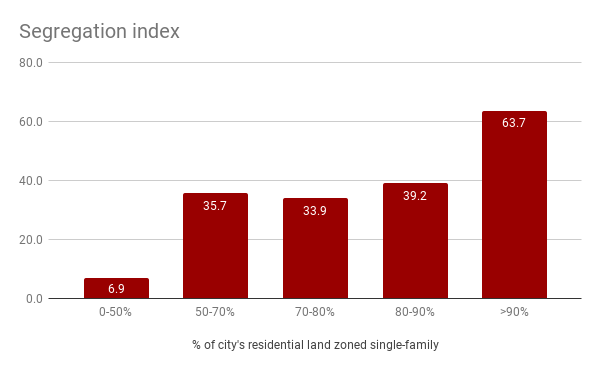

Cities with more widespread single-family zoning are more segregated relative to Los Angeles County as a whole.

Single-family zoning acts as a significant barrier to Black and Latino Americans accessing affordable housing in affluent, high-opportunity cities.

Editor’s Note: City Observatory is pleased to publish this guest commentary by Anthony Dedousis of Abundant Housing LA.

In Part 1 of this series, I examined single-family zoning in the cities of Los Angeles County, and found that cities with more restrictive zoning tend to have higher median incomes, housing costs, and homeownership rates. In Part 2, I dive into the link between zoning and cities’ racial composition, and found that cities with more pervasive single-family zoning tend to have lower Black and Latino population shares, and are more racially segregated relative to Los Angeles County as a whole.

Sadly, this was not a surprising finding: in the United States, income and race are closely linked, and racial discrimination helps to explain much of the wealth gap between white and nonwhite Americans. Also, in many cities, single-family zoning was often introduced as a way to maintain race-based barriers to housing opportunities without violating civil rights laws.

In 1916, Berkeley, California became the first American city to implement single-family zoning; one motivating factor was a desire to exclude Black-owned businesses and families from a white neighborhood. After a 1917 Supreme Court case overturned local laws forbidding Black Americans from purchasing homes in white neighborhoods, many cities used exclusionary zoning as a way around the ruling.

Even after redlining and restrictive covenants were banned in the 1960s, single-family zoning offered an ostensibly race-neutral way to maintain patterns of segregation into the present. Studies have linked more restrictive zoning to lower Black and Latino population shares in Boston-area neighborhoods and in New York’s suburbs. A Berkeley analysis of Bay Area zoning found that cities with more pervasive single-family zoning were likelier to have a higher white population share, higher median incomes, more expensive homes, better access to top schools, and superior access to economic opportunity.

Present-day L.A. County is both incredibly diverse and also highly segregated. While the county overall is 48% Latino, 26% white, 14% Asian, and 8% Black, the racial composition of individual cities varies dramatically. Cities with more widespread single-family zoning tend to be more white, more Asian, less Latino, and less Black. Cities with the least single-family zoning tend to be majority-Latino.

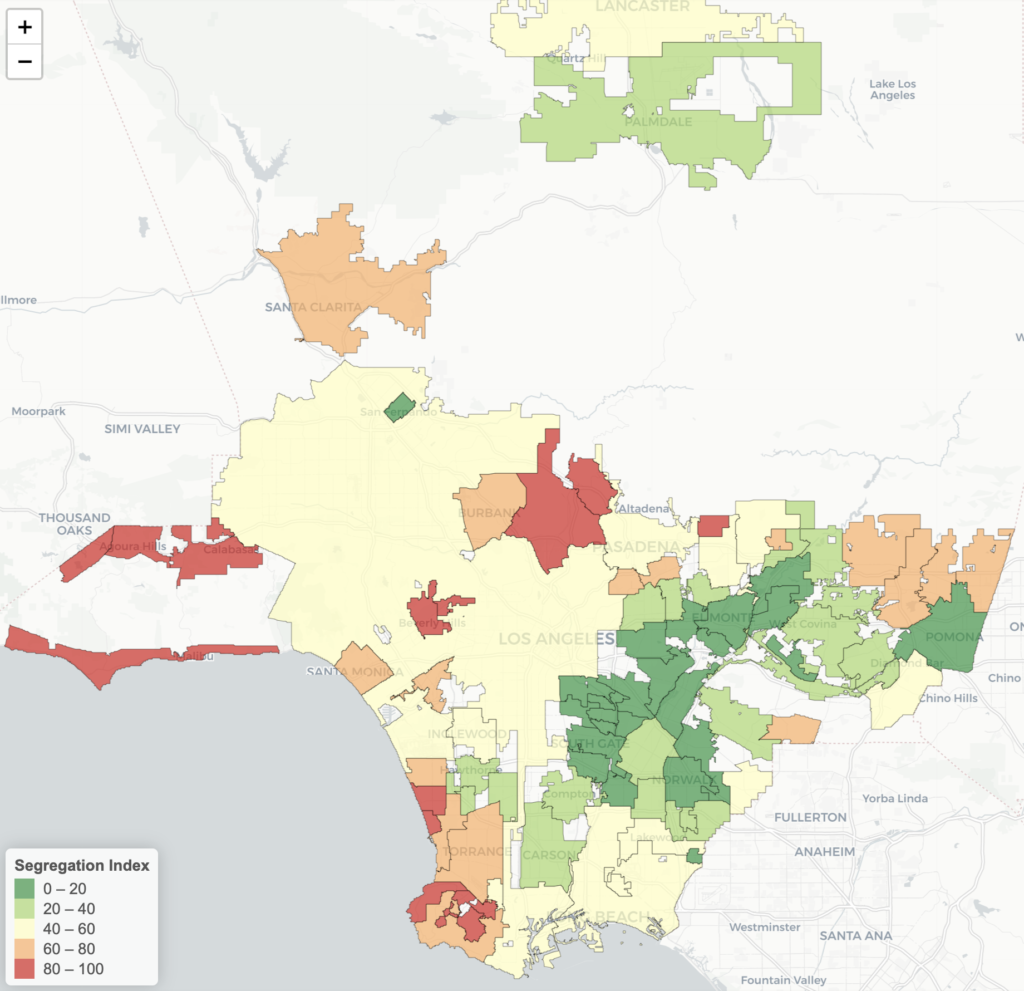

To explore further, I calculated a “Segregation Index” score, which compares each city’s racial composition to the county’s overall demographics. (This is similar to the Divergence Index used as the UC Berkeley team’s preferred metric of segregation, scaled so that 100 would represent the most segregated city in the county.)

In Los Angeles County, cities with higher Segregation Index scores tend to have larger white and Asian populations and smaller Latino and Black communities, relative to the county average. High-income cities in the South Bay and western San Fernando Valley, as well as Beverly Hills, Glendale, and Burbank, have high Segregation Index scores and high prevalence of single-family zoning.

Segregation index by city (100 = most segregated)

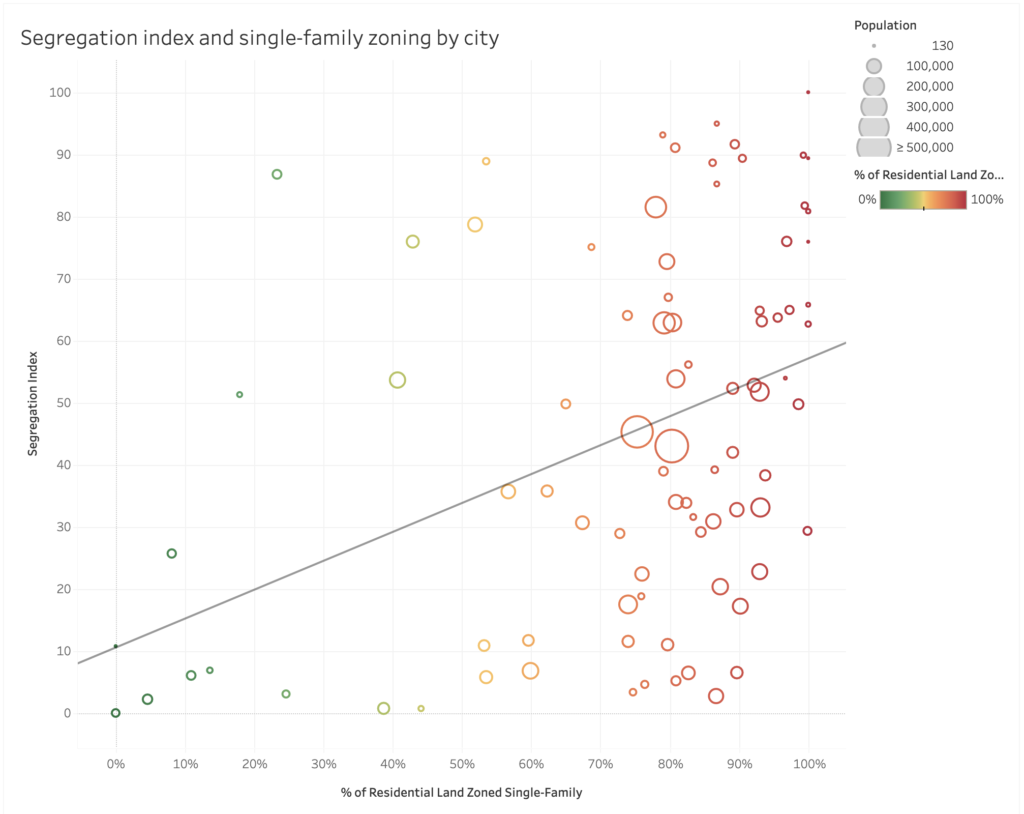

Again, grouping cities into five buckets, based on the prevalence of single-family zoning, shows that cities with more widespread single-family zoning tend to have higher Segregation Index scores. Cities with the most restrictive zoning have Segregation Index scores that are nearly ten times higher than cities with the least restrictive zoning.

Additionally, while not every city with heavy single-family zoning is highly segregated, the most segregated cities generally have widespread single-family zoning.

As with income, this shows how single-family zoning can create or maintain patterns of ethnic exclusion. Single-family homes are more expensive to buy or rent than apartments, and given America’s significant racial income and wealth gap, regulations that mandate more expensive types of housing in a city effectively make that city less affordable to Black and Latino Americans. Barriers to apartment production therefore block many Black and Latino Americans from moving to higher-income areas that offer upward economic mobility, and reinforce the concentration of lower-income families in low-opportunity neighborhoods.

Single-family zoning has a heavy social and economic cost: it makes it harder for families with low or moderate incomes, who are disproportionately Black and Latino, to move to prosperous cities with good schools and jobs. And by raising the cost of housing, it excludes these households from homeownership opportunities. This is profoundly unfair and unnecessary; simply legalizing apartments in these affluent cities would do much to create more affordable housing and homeownership opportunities for people of all backgrounds.

Building a society where opportunity and prosperity are widely enjoyed, regardless of one’s income, skin color, or place of birth, requires us to end single-family zoning. Ending single-family zoning does not mean banning single-family homes. It would simply make single-family houses one of several types of housing that are permissible. Single-family houses would continue to exist alongside duplexes, bungalow courts, and larger apartment buildings, as they already do in neighborhoods throughout California.

Fortunately, a growing number of cities are embracing zoning reform. Minneapolis and Portland were first to legalize small apartment buildings citywide. In 2019, California legalized accessory dwelling units and has seen strong ADU production as a result. Sacramento recently voted to allow up to four homes on any residential parcel, and Berkeley is poised to do the same. Even Santa Monica, no stranger to NIMBY politics, may allow modestly higher housing density in single-family zoned areas.

Legalizing apartments will make these cities more affordable and welcoming to people of all walks of life. It’s time for every city across America to do the same.