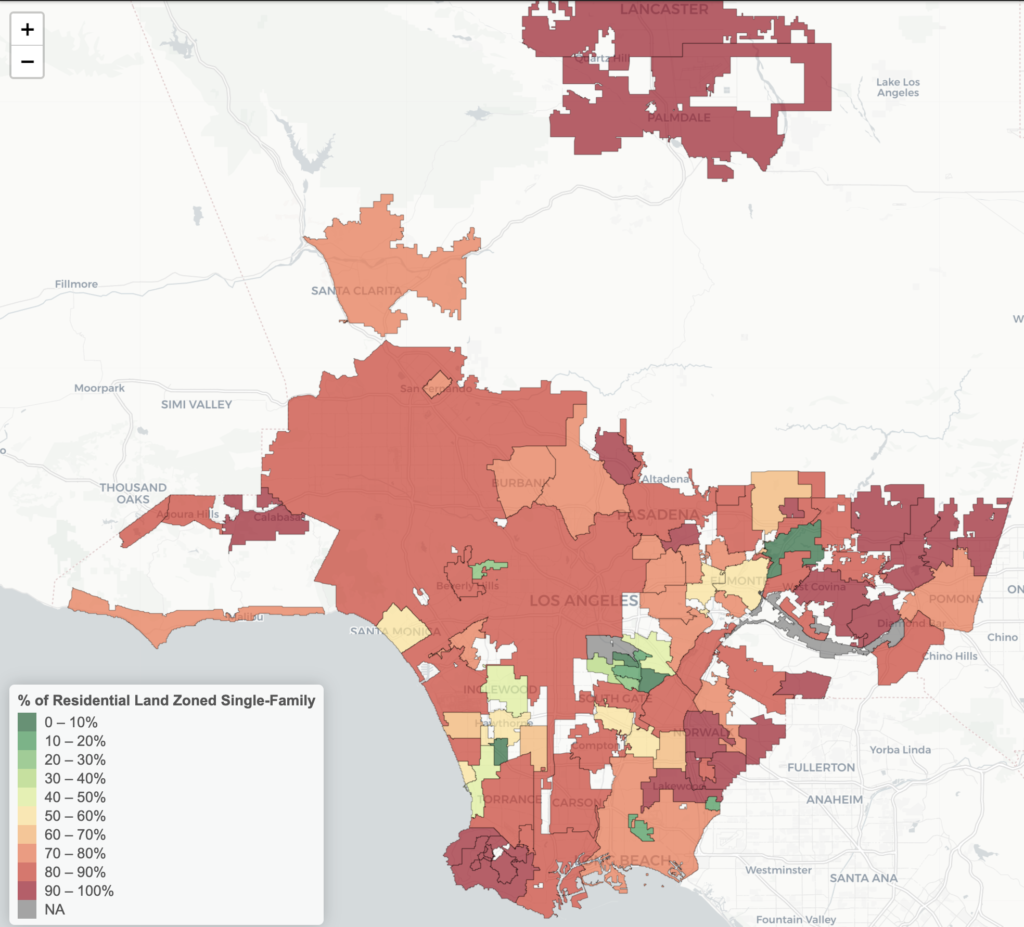

Single-family zoning, a policy that bans apartments, is widespread in Los Angeles County. The median city bans apartments on 80% of its land for housing.

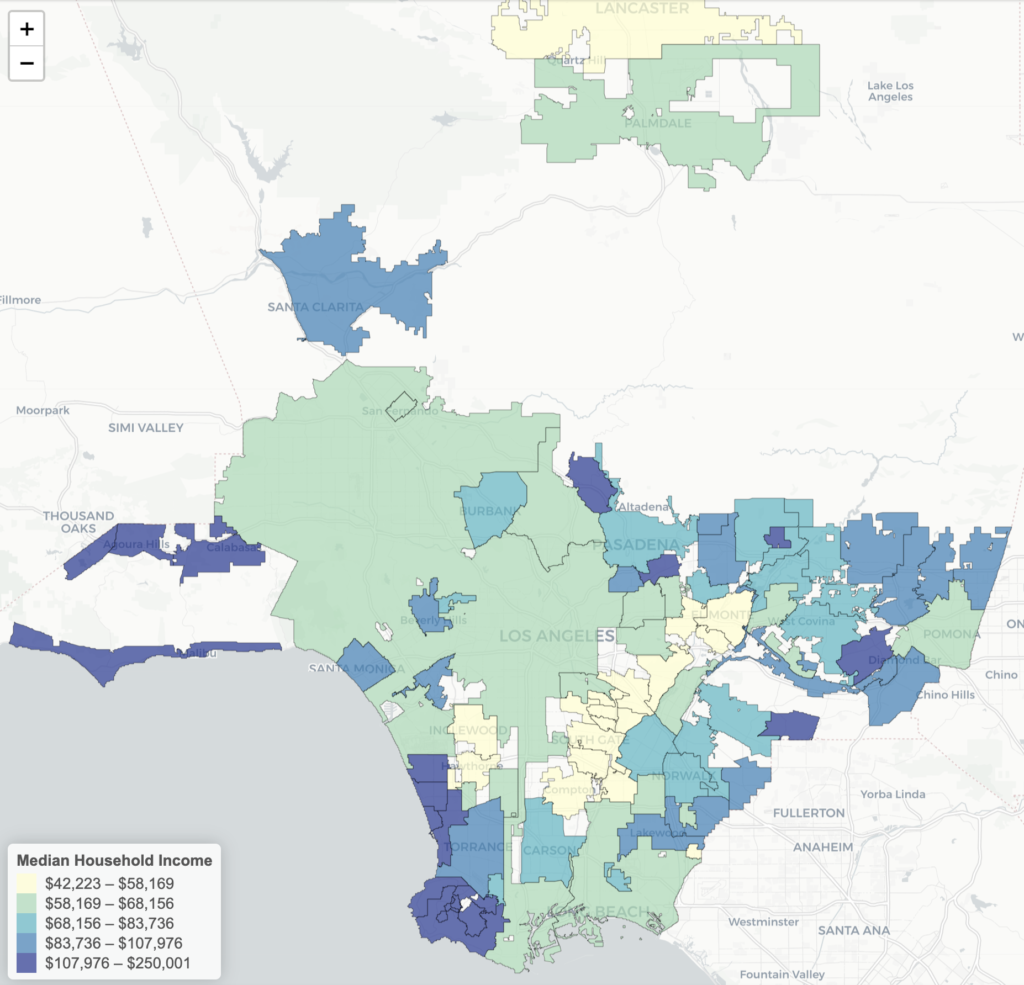

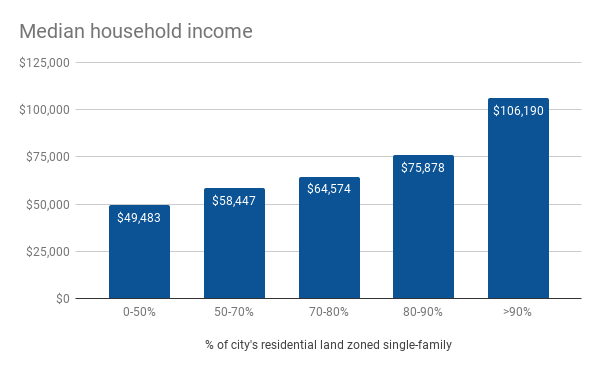

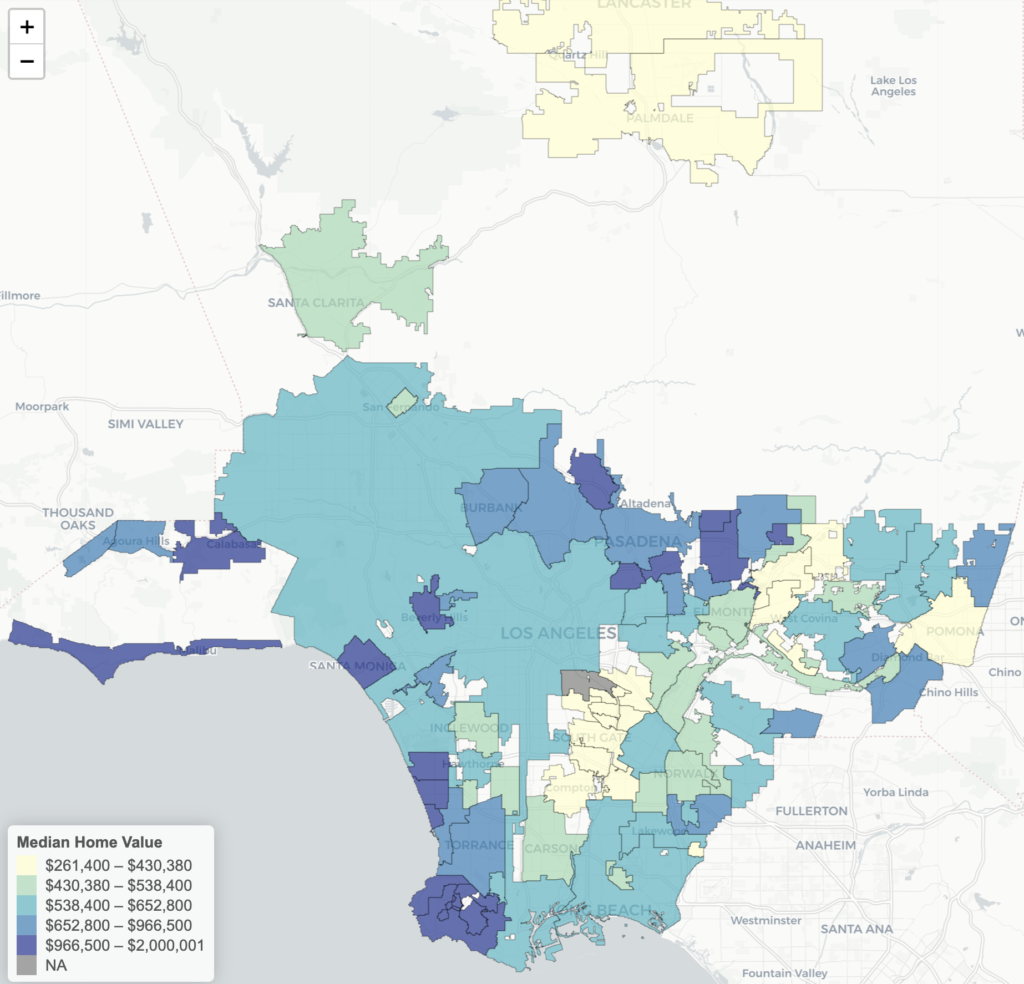

Cities with more widespread single-family zoning have higher median incomes, more expensive housing, and higher rates of homeownership.

Single-family zoning blocks renter households and low- and moderate-income households from accessing affordable housing in affluent, high-opportunity cities.

Editor’s Note: City Observatory is pleased to publish this guest commentary by Anthony Dedousis of Abundant Housing LA.

For over a century, single-family zoning has defined the landscape of American cities. Single-family zoning, which prohibits the construction of apartments, including modest townhouses and duplexes, essentially mandates single-family detached houses as the only legal housing option. While single-family zoning predominates in suburbs, it is surprisingly common even in large cities, where apartments are often banned on over 75% of the land zoned for housing.

When a city limits housing types, it limits who can live in that city. Single-family homes are more expensive than apartments; limiting the housing stock to standalone homes thus raises the cost of living. Single-family zoning fits into a constellation of land use restrictions, including minimum lot sizes and on-site parking requirements, which raise housing costs and create barriers based on income and race.

Here in California, efforts to reform exclusionary zoning and promote denser housing have met with fierce opposition from wealthy homeowners and anti-gentrification activists. Even modest reform proposals like Senate Bill 9, which would legalize duplexes, have attracted hostility from similar corners. As policy and research director at Abundant Housing LA, a “Yes In My Back Yard” organization that advocates for more housing, I sought to better understand the interplay between zoning, income, and race in the Los Angeles area. The outstanding examination of single-family zoning in the Bay Area by the UC Berkeley Othering and Belonging Institute inspired my methodology and interest in this topic.

By analyzing zoning data from the Southern California Association of Governments and demographic data from the American Community Survey, I determined how widespread single-family zoning is in each of L.A. County’s 88 cities. I found that cities with more pervasive single-family zoning tend to have higher median household incomes, higher median home values, higher homeownership rates, and are often more racially segregated.

This two-part series will dive deep into the connection between these variables: Part 1 explores income, housing costs, and homeownership, while Part 2 will focus on race and segregation.

Single-Family Zoning, Income, and Housing Costs

Apartment bans are widespread in L.A. County; the median city zones over 80% of the land for housing as single-family. Even in the City of Los Angeles, America’s second-largest city, apartments are banned on 80% of the residentially-zoned land.

Cities with widespread apartment bans are often high-income enclaves, like Calabasas in the western San Fernando Valley, Palos Verdes Estates in the South Bay, and La Canada Flintridge in the San Gabriel Valley. However, single-family zoning is common even in some lower-income cities, like Compton, South Gate, and Lancaster.

Some pairs of neighboring cities hint at a link between single-family zoning and cities’ socioeconomic makeup. In Lawndale, a lower-income city in the South Bay with a Latino majority, just 8% of the land for housing is zoned single-family. Its neighbor, Torrance, bans apartments on 80% of the land zoned for housing. Torrance’s median household income is $34,000 higher than Lawndale’s, and just 17% of the city’s population is Latino. Other city pairs, like Claremont/Pomona and Cerritos/Hawaiian Gardens, have similar dynamics.

To explore this link, I grouped cities into five buckets, based on their prevalence of single-family zoning:

- 0-50% of residential land zoned single-family (13 cities)

- 50-70% of residential land zoned single-family (11 cities)

- 70-80% of residential land zoned single-family (16 cities)

- 80-90% of residential land zoned single-family (23 cities)

- 90+% of residential land zoned single-family (23 cities)

For those who want more information about individual cities, a here is a spreadsheet showing which zoning bucket each city falls into, as well as other key statistics.

There’s a clear link between more single-family zoning and higher household incomes. In cities with the most single-family zoning, median incomes are more than twice as high as in cities with the least single-family zoning.

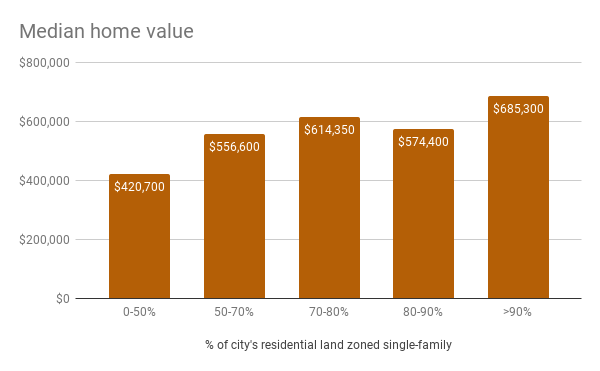

Cities with more single-family zoning also tend to have more expensive homes.

The median home value in the most restrictive cities is nearly $700,000, 63% higher than in the least restrictive cities.

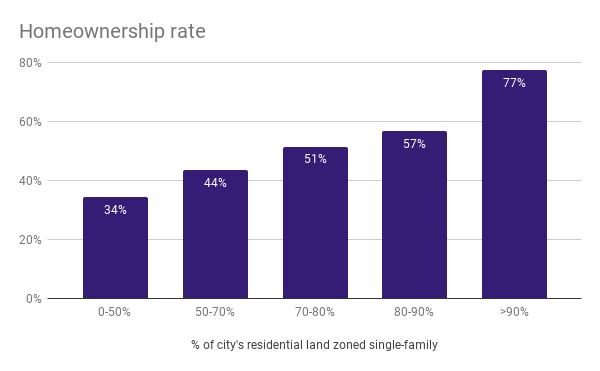

Cities with more single-family zoning also have much higher rates of homeownership, especially in very restrictive cities. This stands to reason: apartment-dwellers tend to be renters, so a widespread ban on apartments acts as a backdoor ban on renter households.

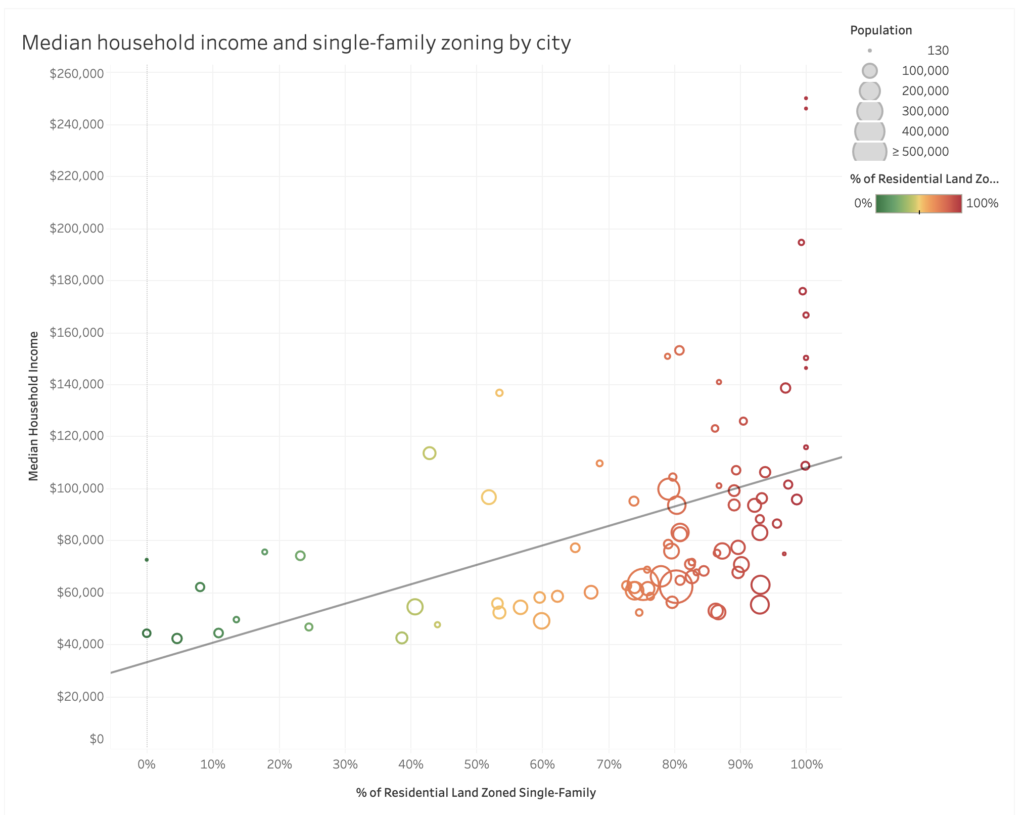

Next, I looked at the relationship between single-family zoning and income for individual cities. Here, it’s important to remember that many suburbs were incorporated explicitly to maintain income and racial barriers; for example, suburban Lakewood incorporated in the mid-1950s to avoid annexation by larger, more urban Long Beach. It’s also worth noting that the City of Los Angeles is by far the largest city in L.A. County by population and area, and that zoning, income, and housing costs vary hugely between the city’s neighborhoods.

With these caveats aside, we can see that nearly every city with a high median household income also has a high prevalence of single-family zoning. There are almost no cities with high incomes and low single-family zoning prevalence, though 20 cities have both high single-family zoning (above 75%) and below-average median household incomes.

Similar patterns emerge when we compare single-family to median home values and to homeownership rates.

Taken together, we can see that cities with wealthier populations, more expensive homes, and higher rates of homeownership are likelier to have widespread apartment bans. Single-family zoning thus acts as a barrier preventing renter households and low- and moderate-income households from accessing affordable housing in affluent, high-opportunity cities, a point that the Berkeley team made convincingly in its Bay Area analysis.

Analyzing housing policy, income, wealth, and exclusion in cities also requires us to analyze race and segregation. In Part 2, I will dig into the relationship between cities’ zoning, racial composition, and prevalence of segregation.