After a long, slow recovery, wages are finally rising for the lowest-paid workers, but we’re no where close to rectifying our inequality problem; in fact, it’s going to get worse.

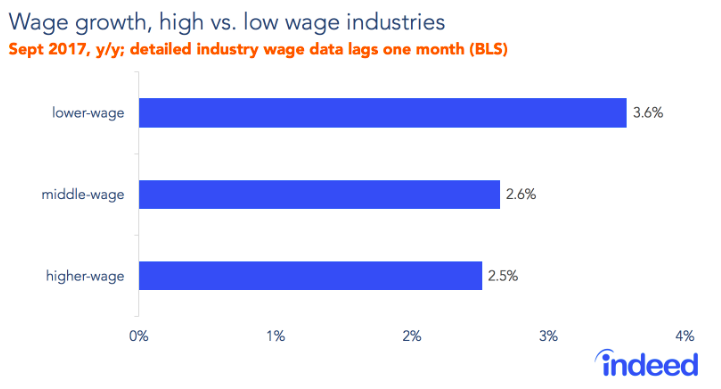

The very smart Jed Kolko, who now writes for labor market website Indeed, offers some keen insights from the latest Bureau of Labor Statistics data. According to Kolko, “The labor market made impressive gains this past year. October 2017 was the 85th consecutive month of job growth. So far in 2017, monthly job growth has averaged 169,000—down modestly from previous years, but more than we’d expect after so many years of recovery and expansion.” The highlight of Kolko’s latest report is the impressive wage gains in the last four quarters for the lowest income workers. Whether measured by educational attainment or wage level, those at the bottom recorded higher wage increases than those at the top.

In a bout of premature triumphalism, Steve LeVine at Axios, is ready to call the whole inequality issue over and done with.

Income inequality — the stubborn curse of the current era and, many think, a key factor in the global uprising against establishment powers — appears to be on a solid decline in the U.S., according to a new report.

While the recent gain in wages for the lowest paid workers is definitely good news, it is hardly the reversal of America’s yawning income gap. Far from it. Not only does a single sparrow not make a spring, there’s plenty of evidence that the inequality problem is not only not going away, but that it’s likely to get worse. There are four reasons why:

First, the wage gains for low income workers so far are small

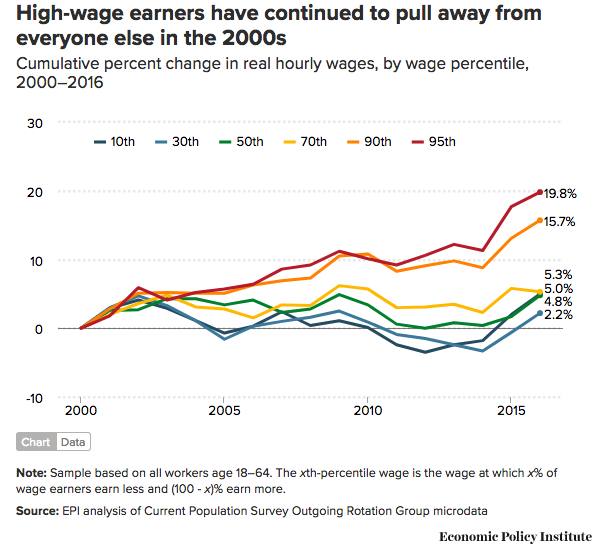

it would take a decade or more of such performances to offset the widening in wage inequality that’s happened in just the last decade or so. The tale of the tape comes from the Economic Policy Institute, which uses Census data to track cumulative changes in real hourly wages since 2000 by income group. Those in the 90th percentile have seen a nearly 16 percent increase in real wages, while those in the bottom 10 percent have seen just a 2 percent increase in real wages. In the past year, real wages for the least skilled (per Kolko’s analysis of BLS data) have outpaced those of higher skilled workers by about 1 percent. So we’d have to see these gains, year-in and year-out, between now and about 2030, just to get back to the level of wage inequality we had in 2000.

EPI‘s headline finding has it exactly right: “More broadly shared wage growth from 2015 to 2016 does little to reverse decades of rising inequality.”

Second: Wages aren’t all income

Inequality is actually a much bigger issue that the variation in wages between high skill and low skill workers. Wages are just one component of income. Other forms of income (dividends, interest, rent, business profits) are all much more unequally distributed than wages, and it’s been these latter forms of income, per Thomas Piketty and others, that have fueled much of the growth in inequality. Aggregated across all forms of income, the gains over the last third of a century have been heavily skewed to those at the top, as we reported at City Observatory a few months back.

Third, The Fed is likely to break up the game

In a macroeconomic sense, the gains that the lowest income workers are seeing is the long-awaited result of more than eight years of economic growth. The recovery from the Great Recession (which actually began exactly 10 years ago, in December 2007, according to the NBER), has been slow. Higher skilled and higher income workers have seen the best employment and wage gains throughout the recovery. It’s only as the national unemployment rate has finally fallen below five percent that lower income workers are starting to see similar results. But its very much an open question as to whether a skittish Federal Reserve Board–the one that sees incipient inflation around every corner–is willing to continue to allow the economy to grow. It’s already started raising interest rates, and promises to raise them further in the coming year. That will likely slow the economy, and with it, curb the gains that the least well-off workers have enjoyed in the past couple of years.

Fourth, The new tax bill is about to make inequality far worse.

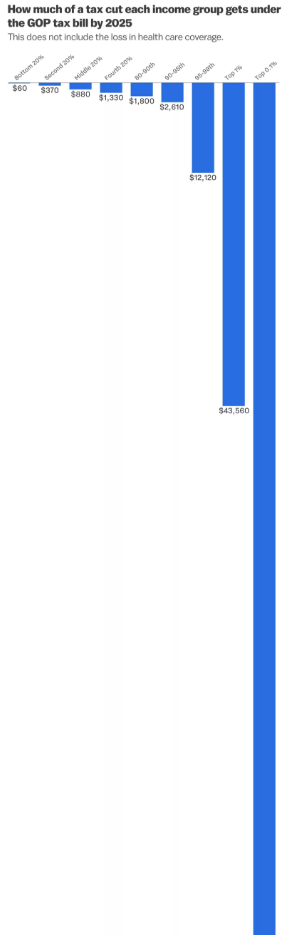

You can’t talk about inequality without talking about the tax system. One major source of the growth in inequality has been the differential taxation of high income households and non-wage income. Since 1980, in the US effective tax rates have been slashed for the highest income households and for the kinds of income and wealth they hold, including property, stocks, bonds and estates. (That’s why the difference between the red line “pre-tax” line and the blue “post tax” line in the chart above is so small). And if the tax plan currently before Congress moves forward, that’s going to get dramatically worse. The trillion dollar plus tax cut goes overwhelmingly to those at the top of the income spectrum. Vox has an analysis showing the average tax cut by income group in 2025:

Moreover, the tax cuts will undoubtedly trigger a big increase in the deficit, which will likely be used as an excuse for shredding of the social safety net, with cuts to Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, and other programs that ameliorate the effects of income and wealth inequality.

In sum, it’s a very good thing that the labor market has finally recovered to the point where the lowest income workers are enjoying a small increase in their wages. But that’s hardly a justification for calling America’s decades-in-the-making income inequality chasm closed. It’s still dauntingly large and promises to get even worse.