- Gentrification is a big issue in a few places, and not an issue at all elsewhere.

- Big cities with expensive housing are the flashpoint for gentrification.

The city-policy-sphere is rife with debate on gentrification. Just in the past weeks, we have a French sociologist’s indictment of bourgeois movement to the central city, the Mayor of Washington and the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development pointing to 300 new units of affordable rental housing as a bulwark against gentrification in DC’s fast-changing Shaw neighborhood, and continued debate over the merits of a moratorium on new housing development as a means of stemming change in San Francisco’s Mission District.

Most of the stated concern about gentrification revolves around the belief that neighborhood improvement automatically produces widespread displacement of the existing population. But how widespread is the problem?

Outside a big cities with tight housing markets, the effects of gentrification may be much more benign. In an essay entitled “Is gentrification different in legacy cities?” Todd Swanstrom argues that in most of the nation’s metros, the effects of gentrification are more muted, and on balance positive. Because housing prices are low and there is a lot of slack in the housing market, the movement of better educated and higher income people into cities is far less likely to result in the displacement of the existing population.

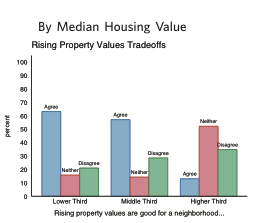

The variety of opinions about the effects of gentrification are apparent when one talks to mayors. Consider the results of a 2014 survey of the nation’s mayors undertaken by Boston University. The survey explored mayoral attitudes about gentrification, asking them whether they agreed, disagreed or neither agreed nor disagreed with the proposition that “rising property values are good for a neighborhood.” Overall, of the 70 mayors surveyed, 45 percent agreed and 30 percent disagreed with this statement. The pattern of responses is highly correlated with property values: mayors of cities with median home values in the bottom and middle third of the national distribution agreed by a more than two to one margin that rising values are good, compared to only about 20 percent of the mayors of cities with the most expensive homes.

Mayoral Opinion on “Rising Property Values”

Source: Boston University Initiative on Cities, Mayor’s Leadership Survey

Another way of tracking public awareness of the issue is through data on Internet searches. Google data confirm that public interest in gentrification is increasing. The increase has mostly been strong and steady, with a very strong spike coinciding with Spike Lee’s famous anti-gentrification rant at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn in February, 2014.

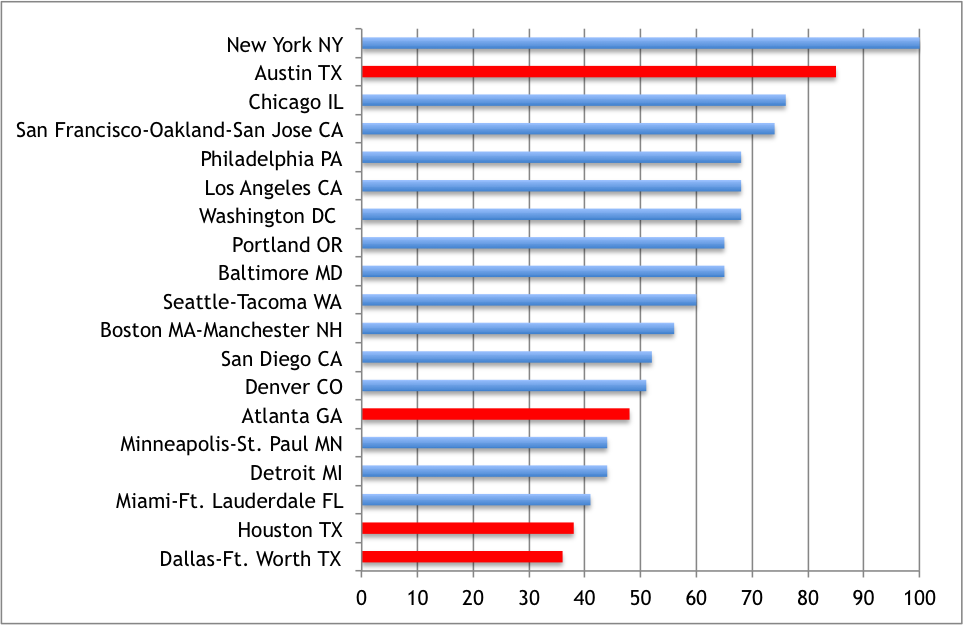

The Google data also show a distinctive geographic pattern to the interest in gentrification. Google Trends reports the metropolitan areas with the greatest relative propensity to search for specific terms, including gentrification. Searches for gentrification come disproportionately from a handful of large metropolitan areas, corresponding to some the nation’s largest and most liberal cities: New York, Austin, Chicago, San Francisco, and Washington head the list. And 32 of the 51 largest US metropolitan areas have reported values of zero for searches related to gentrification.

Top Metropolitan Areas for Gentrification Searches

Source: Google Trends, Page Rank Index for “Gentrification” Relative to Top Metro (New York). Metros color-coded based on statewide presidential vote in 2012, blue-democratic, red-republican.

All of the other metropolitan areas in the country have an index value of zero in Google Trends, indicating almost no interest in the subject.

Fifteen of the nineteen metropolitan areas on this list, including 12 of the top 13 are located in blue states (based on statewide vote for president in 2012). It’s been argued elsewhere that liberals have done a lousy job of fighting gentrification, and these data at least superficially support this argument.

A common factor in gentrification is a surging demand for urban living in the face of a limited supply of urban housing. We haven’t undertaken a detailed analysis of the housing markets in the cities where gentrification interest is strongest, but they map to largest cities with robust housing markets (with the exception of Detroit). In smaller markets, and where housing is relatively inexpensive, gentrification doesn’t seem to register as an issue, as measured either by Google Trends or mayoral opinion.

Its instructive to look at the relationship between metro area population, housing prices and interest in gentrification. The following table stratifies the nation’s 51 largest metropolitan areas – all those with a population of one million or more – by population size, and looks at average home prices (reported by Zillow) in metros with, and without, a reported interest in gentrification (as indicated by the Google Trends data discussed above).

Several findings stand out. First, interest in gentrification is universal among the 12 largest metropolitan areas, but decreases rapidly as metro area population falls: half of the second quartile of large metros, two the next quartile and none of the last quartile had a measurable interest in gentrification, according to the Google search results. Second, home values tend to be much higher in metros with an interest in gentrification: average prices are about 50 percent higher in the second quartile, and about three times higher in the third quartile. As the final column suggests, home prices tend to be higher in larger metros, but the smaller metros that have an interest in gentrification have average home prices that are higher than in the largest 12 markets. Interest in gentrification is strongly related to market size and to high home prices. As John Buntin speculated in Slate, the high interest in gentrification in pricey coastal real estate markets may have more to do with middle class concerns about affording real estate than about the displacement of the poor.

| Average Home Value in Markets by Interest in Gentrification | ||||

| Average Home Value | ||||

| Market Size | Number Interested | Interested | Not Interested | Value All Markets |

| 12 Largest | 12 | 297,267 | NA | 297,267 |

| 13th-24th | 6 | 308,850 | 205,467 | 257,158 |

| 25th-36th | 2 | 550,600 | 154,720 | 220,700 |

| 37th-51st | 0 | NA | 164,513 | 164,513 |

Source: Google (Gentrification Interest), Zillow (Home Prices)

Most cities have strong limitations on dense development, particularly in the most desirable neighborhoods, so when housing demand surges, it leads to price increases and development pressure that is felt in lower income neighborhoods. In sprawling markets where the housing supply is relatively elastic (Atlanta, Houston, Dallas) gentrification is far less of an issue; and as noted above, it seems to be a non-issue in most Sunbelt cities (for example Phoenix, Jacksonville, Tampa, Nashville, Charlotte).

These data show that interest in gentrification, while growing is still a highly localized issue: it tends to be a concern in large cities, not small; in expensive housing markets, not affordable ones, and is disproportionately of interest in common in blue states, and relatively rare in red ones.