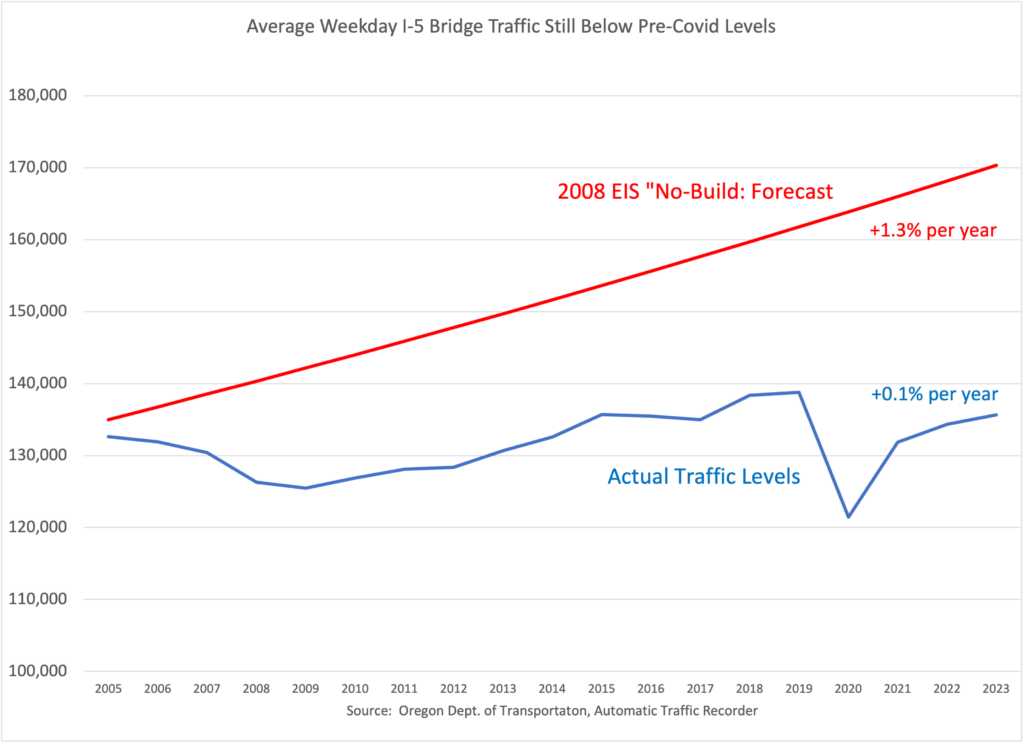

The Interstate Bridge Project’s traffic projections pretend that the massive shift to “work-from-home” never happened

The IBR traffic projections rely almost entirely on pre-Covid-pandemic data, and ignore the dramatic change in travel patterns.

Traffic on I-5 is still 7 percent below pre-pandemic levels, according to Oregon DOT data

Traffic on the I-5 bridge is lower today that the purported 2005 baseline for the Columbia River Crossing project (135,000 vehicles per day).

Post-covid travel analyses have shown a permanent shift toward lower growth in vehicle miles traveled.

It’s a violation of NEPA to ignore scientific evidence that travel patterns have shifted and spend $7.5 billion on a project for a world that no longer exists.

The Interstate Bridge Replacement project’s traffic and revenue forecasts appear to be built on increasingly shaky ground. New data from multiple transportation agencies shows that post-pandemic travel patterns have dramatically diverged from pre-pandemic trends, calling into question the fundamental assumptions underlying the multi-billion dollar project. Traffic is now lower, and growing more slowly than prior to the pandemic, contrary to the assumptions built into IBR traffic projections.

The Covid Pandemic and work-from-home fundamentally changed traffic patterns, and there’s no evidence that growth has reverted to even its very weak, pre-pandemic trend. ODOT statistics show bridge traffic in 2023 was no higher than in 2015.

Recent analyses from both Oregon and Washington state transportation departments reveal that systemwide traffic volumes have not only failed to return to pre-pandemic levels but show signs of a persistent structural shift in travel behavior. The Oregon Department of Transportation reports that I-5 traffic in Portland remains 7 percent below 2019 levels in 2023 – an even larger decline than the 6 percent reduction observed two years earlier. This suggests that rather than recovering, the post-pandemic traffic reduction is becoming more pronounced over time. A 2023 report, authored by ODOT traffic counting expert Becky Knudsen reports that traffic volumes on I-5 are lower now than in 2019, and have not increased following the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic.

Becky Knudsen, “Pandemic Impacts on Future Transportation Planning: Implications for Long Range Travel Forecasts”, ODOT, July 2023.

The picture in Washington State is even more striking. WSDOT’s mobility dashboard shows that congestion-related delays on Clark County’s three main roadways have plummeted by over 75 percent compared to pre-Covid levels. This dramatic reduction in congestion suggests that the “traffic crisis” used to justify the massive bridge project may be largely resolving itself through changed travel patterns.

The Interstate Bridge Replacement project’s own data confirms this trend. Their Level 2 analysis reveals that average weekday traffic in October 2022 was still 4.8 percent below 2019 levels, with just 136,500 daily crossings compared to 143,400 before the pandemic. At the historical pre-pandemic growth rate of 0.3% per year, it would take until 2039 – a full 15 years after the projected bridge opening – just to return to 2019 traffic levels.

These local trends reflect broader national shifts in travel behavior. The Federal Highway Administration has dramatically scaled back its projections for future driving growth. While their 2019 forecast predicted light vehicle travel would grow by 1.1 percent annually over 20 years, their 2023 update slashed that projection nearly in half to just 0.6 percent per year. This reduced growth trajectory acknowledges the pandemic’s acceleration of trends like remote work and e-commerce that have fundamentally altered travel patterns.

Research from other states reinforces these findings. The Maryland Department of Transportation estimates that pandemic-induced behavioral changes have permanently changed driving trends. They conclude:

VMT under all scenarios is estimated to be less than VMT under “Old normal” (Pre-pandemic conditions) scenario. It is estimated that 2045 total VMT reduction because of COVID-19 ranges between 3 % and 12 % with an average of 7 % across all scenarios.

Shemer, L., Shayanfar, E., Avner, J., Miquel, R., Mishra, S., & Radovic, M. (2022). COVID-19 impacts on mobility and travel demand. Case studies on transport policy, 10(4), 2519–2529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2022.11.011

Even Stantec, the consulting firm preparing traffic and revenue forecasts for the Interstate Bridge project, acknowledges these risks. Their Level 2 report—not included in the DSEIS— explicitly warns that “potential risks and uncertainties may be magnified by the transitory or permanent effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mobility, travel, and the economy.”

Yet despite this warning, the IBR project continues to rely on pre-pandemic assumptions that appear increasingly divorced from reality. The Draft Supplemental Environmental Impact statement makes a vague claim that traffic levels are “similar” to pre-covid levels, and claims that it is following “industry standard” practices to simply ignore everything that happened after 2019:

Transportation analyses generally incorporate the most recently available data. However, due to the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on travel patterns between 2020 and 2023 as explained above, the most recently available data is not representative of standard conditions. Therefore, the IBR Program is following industry standards and using 2019 as the baseline year for the existing conditions instead since it most closely resembles standard conditions.

DSEIS, Transportation Technical Report, page 3-2.

The DSEIS also claims that it can continue to rely on the pre-covid Metro “Kate” travel demand model, even though this model doesn’t incorporate any post-2019 data, and also over-predicts current traffic levels on I-5 by nearly 20 percent. The DSEIS offers no documentation regarding “industry standards” or explanation for why it simply ignored work-from-home and the impact of the Covid pandemic on travel patterns, and its own data.

This disconnect between projections and reality has serious implications. If traffic volumes remain substantially below forecast levels, toll revenues will fall short of expectations, potentially leaving taxpayers on the hook for billions in additional costs. The project’s financial plans assume robust traffic growth to generate toll revenues needed to repay construction bonds. But if post-pandemic travel patterns persist, those revenue projections will prove wildly optimistic.

Before committing billions in public funds to a massive infrastructure project predicated on continued traffic growth, project leaders need to squarely address this new reality. The evidence increasingly suggests we’re not experiencing a temporary pandemic dip, but rather a fundamental shift in how people travel. Proceeding with plans based on outdated pre-pandemic assumptions risks building – and paying for – infrastructure sized for a future that may never materialize.

A prudent approach would be to pause and reassess the project’s scope and assumptions in light of these documented changes in travel patterns. The pandemic has given us an unexpected opportunity to rethink our transportation needs. We should take advantage of this moment to ensure our infrastructure investments align with actual trends rather than outdated projections.