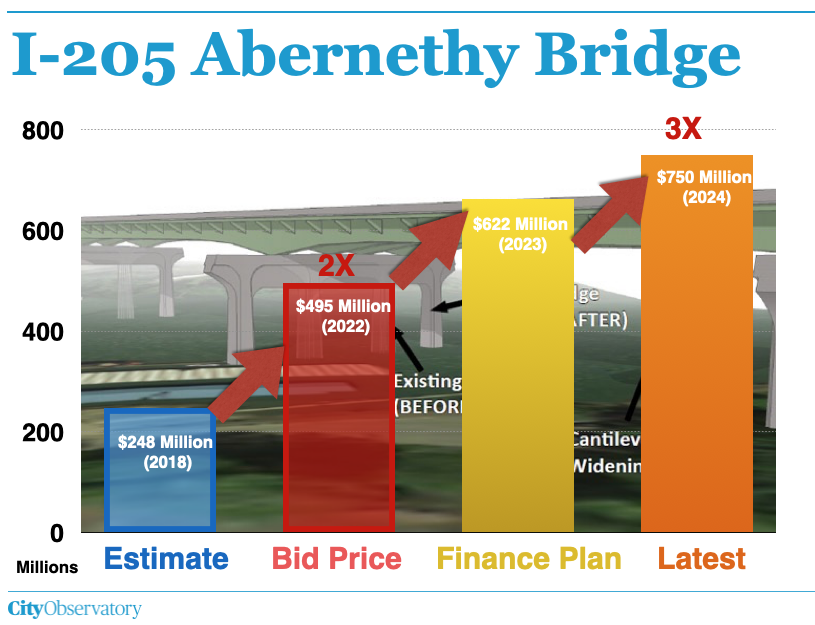

Oregon DOT’s I-205 Abernethy Bridge rebuild, advertised as costing $248 million, will really cost $750 million

The project’s estimated cost has tripled in just over five years, and still has further cost overrun risk

ODOT’s plans to cover these cost overruns would mean cancelling dozens of other projects around the state, and/or a huge statewide gas tax increase

The Oregon DOT has experienced massive cost-overruns on all of its largest construction projects, and has systematically concealed and understated the frequency and scale of cost overruns

The I-205 Abernethy Bridge: Now three times as expensive

This is at least the third cost-overrun for the Abernethy Bridge project. ODOT originally told the Legislature in a 2018 that the project would cost $248 million. When bids were opened in 2022, the cost of the project doubled to $495 million. As soon as ODOT began construction, there were further cost increases, to $662 million. And now, ODOT admits it will cost $750 million to build the project—three times what it told the Legislature when the project was allowed to go forward. The latest cost overruns are revealed in the meeting materials for the May 9th, 2024 Oregon Transportation Commission meeting.

The estimated cost to complete construction of the I-205 Abernethy Bridge Project has increased for a number of reasons, including structural engineering elements, unanticipated project changes, and delay, escalation and risk for a multi-year project.

Who will pay? Robbing money from other projects statewide, or raising everyone’s taxes

Background on the Abernethy Bridge Cost Overruns

For some years, the idea of widening and seismically retrofitting the I-205 Abernethy Bridge across the Willamette River between Oregon City and West Linn (in Portland’s southern suburbs) has been on the wish list of state and local transportation officials. The Legislature didn’t fund the project as part of a major transportation package in 2017, but did direct ODOT to produce a “cost to complete” report so that it would have some idea of how much money would be needed. ODOT produced that report in 2018. It said that retrofitting and widening the bridge would cost $248 million (The bridge project was identified as “Package A” in this cost estimate..

Armed with that figure, highway advocates pushed forward, and in getting the Legislature to direct ODOT to take on the project. But—and we know you won’t be surprised—ODOT’s estimate was wrong—very wrong. In the Fall of 2021, ODOT prepared a “construction phase cost estimate” of $375 million, which represented a 50 percent increase in costs over its “cost to complete” report. When the project went to bid in 2022 bids came back at just a shade under $500 million. As is common practice, the original 2018 estimate was officially forgotten when reporting the further escalation of costs in 2022, with ODOT reporting only the additional cost increase of roughly $125 million, not the full cost increase of $250 million from its original estimate. The key takeaway though, is that, in the space of just over five years, the cost of this project tripled.

Deja vu all over again.

Regular City Observatory readers will no doubt have a sense of deja vu. Cost overruns are endemic to major ODOT projects. The Interstate Bridge Replacement project, advertised as costing $4.8 billion in 2020, has increased to $7.5 billion, and may likely go to $9 billion. The I-5 Rose Quarter freeway project, originally billed as costing $450 million has had a series of cost overruns, first to $795 million, then $1.45 billion and now $1.9 billion—and further increases are likely. The Abernethy Bridge, the Interstate Bridge Replacement Project are all massively expensive, already costing more than $1 billion per mile.

ODOT Cost Overruns: The Reign of Error

To some, a cost increase of this magnitude may seem like an aberration. For anyone who has followed ODOT closely, its apparent this is very, very common. This isn’t a recent phenomenon—it’s a well established pattern. Over the past two decades, ODOT has blown through the budget estimates of virtually every large project they’ve undertaken.

Like other highway agencies, ODOT has consistently underestimated the cost to complete its major highway projects. A review of ODOTs own reports for the largest projects its undertaken in the past 20 years shows a consistent pattern of cost overruns, as summarized here: