The myth of a freight dependent economy: debunked by a thriving reality

Imagine a port city, whose port went away. It’s economy would surely wither and die, right? That’s what you might expect if you believed decades of civic shibboleths about the Portland having a freight dependent economy.

The symbol of is the marine crane. The icon is the shipping container.

The city’s official creation myth usually began with the sonorous incanantation “A the confluence of two mighty rivers”–the widespread belief that Portland’s destiny was pre-determined by geography and navigable waterways. When “port” is your city’s first name, it hard to escape the idea that moving stuff is what drives your economy. And to be fair, in the 19th century, shipping grain and lumber to markets around the world, and building ships did account for a fair amount of the city’s economy. But that’s changed dramatically. The port’s importance faded, first with the shift from wood and sails, to steam and steel, and then for the past half century, with the advent of larger and more centralized container ports.

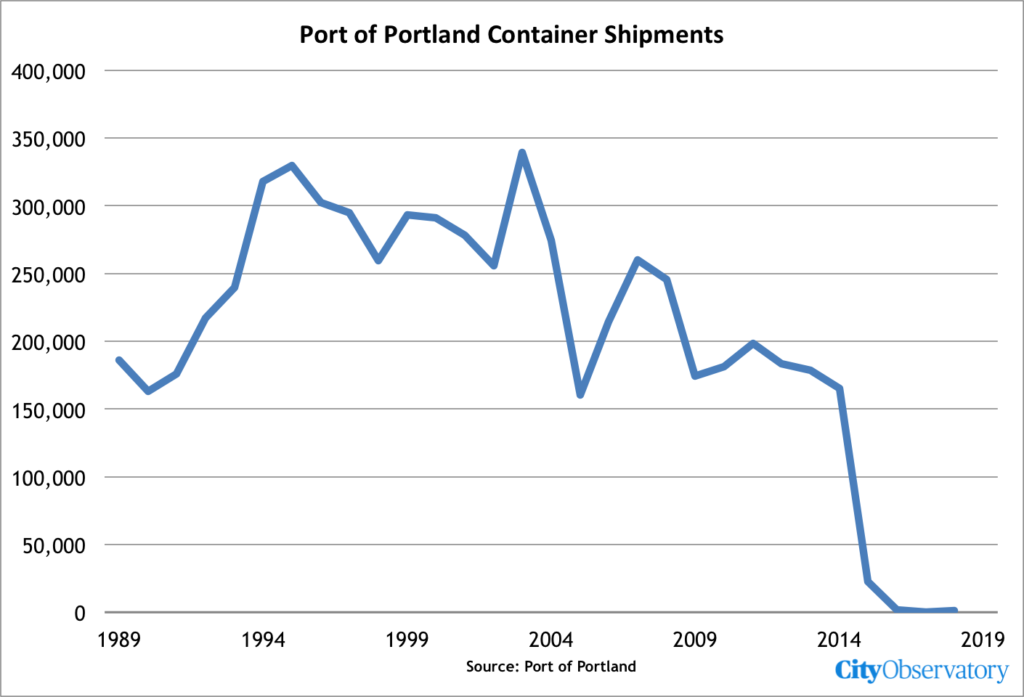

Portland was pretty much always a bit-player in the container business–in a good year, it barely handled 1 percent of West Coast container traffic. And in an industry increasingly dominated by large scale–both in port operations and giant post-Panamax container ships–Portland was decidedly uneconomical. In desperation, the Port of Portland subsidized container service for a time, but in 2015, the last two shipping firms pulled out, and in 2017, not a single container was loaded or unloaded from a ship in Portland. Portland which once handled 300,000 containers, now handles barely a thousand in the past year. (Los Angeles and Long Beach can load and unload more than that in a few hours).

And did the city’s or the region’s or the state’s economy collapse? Hardly–the region continues to grow more rapidly, and is larger than ever. The loss of container service had no discernible effect on Portland employment or income growth.

And while local container service disappeared, that had virtually no impact on exports. In fact, the state reported that its exports were a record $18 billion in 2018–chiefly because high value products like transportation equipment, semiconductor machinery, and electronics don’t get shipped by container. Over the past ten years, according to the Brookings Institution, metropolitan Portland has racked up the fifth best performance in terms of economic prosperity of the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas, even though its container port essentially disappeared.

Employment data show that since the end of the great recession, Portland’s economy has dramatically outperformed the nation. And unlike the previous economic expansion, which ended in 2007, Portland’s economy has done well through the recovery and pulled progressively further ahead as the expansion matured. Thus, despite losing container service, the economy has flourished.

In truth the city and its principal industries have since long outgrown their dependence on marine traffic. The port hasn’t entirely gone away: while containers and break-bulk traffic have disappeared, there are the trappings of maritime commerce. The marine activities at the Port now consist of moving cars (chiefly unloading imported cars from Asia), and exporting bulk wheat and potash. The city’s marine operations look like those of a resource-dependent third-world country: exporting raw materials, importing finished goods. While that sounds grim, it’s essentially irrelevant to regional economic health because Portland has excelled at growing and creating new knowledge-based industries that are utterly independent of marine commerce.

For example, the region’s two iconic industrial powerhouses–Intel and Nike–ship essentially nothing over the region’s docks. Intel never did–it’s chips move to world markets by air. Nike closed its local warehouses almost two decades ago–it moves its products through the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach and and a national distribution center in Memphis. The high value work of designing shoes and apparel, and running a global branding and marketing machine is in Portland.

And what of the Port of Portland, the municipality charged with running the region’s marine terminals? While it used to think its business was centered on the movement and storage of metal boxes–the containers that moved on and off ocean liners–it’s business has changed, but in important respects is the same: Perhaps the Port’s biggest money maker is the still the movement and storage of metal boxes–but instead of shipping containers, they are the travelers’ cars moving through and parked at Portland International Airport–where the port collects more than $80 million in revenue annually from its parking garages, and fees in charges rental car operators, taxis and ride-hailing firms.

It’s easy to be mesmerized by the icons of an earlier industrial age, whether its massive factories, or belching smokestacks or container cranes. But the health of metropolitan economies today is really about building great urban spaces that attract and retain smart people, and create an environment where they can easily connect with one another to generate new ideas. Perhaps one day we’ll have a mythological description of that process that is as captivating as the iconography of marine commerce. Until then Portland will have to satisfy itself with having built a thriving economy based on a narrative it hasn’t fully written or embraced.

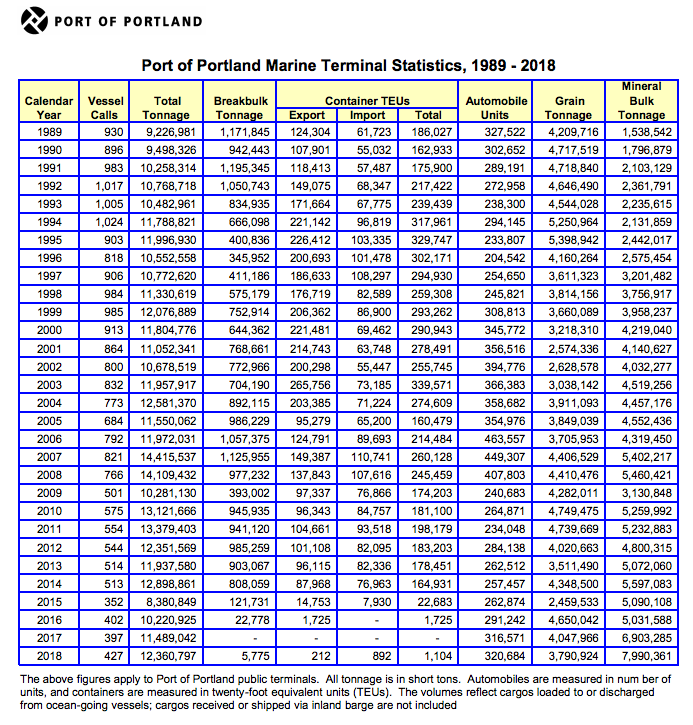

Appendix

For reference, we’ve reproduced the Port of Portland’s 30-year summary of maritime activity below.