When we talk about gentrification, we often focus on housing. But another major concern is the effects of rising prices on retail—both because of what it means about the accessibility of goods and services for local residents, and because of questions of “community character.”

The Philadelphia Federal Reserve Bank’s recent symposium on gentrification included a paper from Rachel Meltzer of The New School on just this subject. Meltzer begins by indicating two ways that gentrification might affect small businesses: changing the kinds of goods and services that local residents demand, and changing the cost of doing business, making some lower-margin businesses no longer profitable.

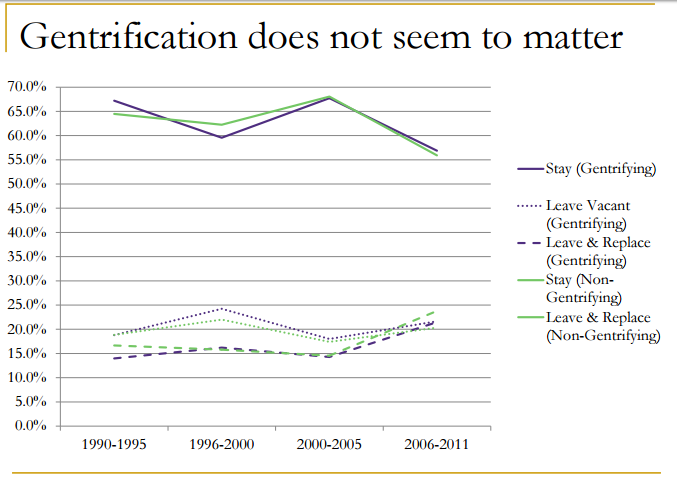

Meltzer then explores data from New York City between 1990 and 2011 to look at how small business retention rates vary between neighborhoods that are gentrifying, and those that aren’t. The overall results, perhaps counterintuitively, show virtually no difference. In fact, the percentage of small businesses that leave their storefront and are replaced by another business—the kind of scenario you’d expect to see in a gentrifying neighborhood, with (say) bodegas getting replaced by artisanal coffee shops—is very slightly higher in non-gentrifying neighborhoods than in gentrifying ones.

The essential fact here is that local storefront businesses have a high rate of turnover generally. So while there are lots of examples of businesses going out of existence in gentrifying neighborhoods, there are lots of examples in other kinds of neighborhoods as well.

At a closer-to-the-ground level, looking at differences in business retention between Census tracts in the same neighborhoods, Meltzer does find some distinctions: Businesses are less likely to leave without a replacement—that is, create a vacancy—but somewhat more likely to leave with a replacement in gentrifying areas.

The takeaway is not necessarily that business displacement never happens in gentrifying neighborhoods—plenty of people in high-cost cities can cite a favorite old business that relocated or disappeared because of rising lease costs.

Rather, the results of this study on retail displacement are strikingly similar in some ways to the results of studies about residential displacement: while there are certainly examples of it happening, systematic studies that compare gentrifying and non-gentrifying neighborhoods repeatedly fail to find that there’s significantly less displacement in non-gentrifying neighborhoods. And just as rising apartment rents may sometimes be offset by an increased willingness to pay because of better neighborhood amenities, rising retail lease prices might be offset by more and higher-income customers who are willing to pay more or buy more high-margin products. More customers with more disposable income translates into higher sales, which can enable businesses to still profit while paying a higher rent. On the other side, just as non-gentrifying low-income neighborhoods usually see a kind of “displacement,” with rapidly declining populations as people leave for areas with stronger neighborhood amenities, local businesses in these neighborhoods may also struggle to remain in a place with a declining customer base. In these struggling neighborhoods, low or stagnant incomes mean relatively lower sales for local merchants, making it hard for them to be profitable, even if rents are low.

In other words, with business displacement as with residential displacement, the reality of gentrification appears to be much more complicated than prevailing narratives. It is not clear that gentrification leads to higher levels of small business turnover.