Overall, America is becoming more diverse, but in many places the neighborhoods we live in remain quite segregated. The population of the typical US metropolitan area has a much more ethnically and racially mixed composition than it did just a few decades ago. Overall, measured levels of segregation between racial and ethnic groups are declining. But change at the neighborhood level, particularly in the neighborhoods that are home to the “typical” white family, have changed more in some places than others.

Our interest in this subject was kindled last month with an analysis of the latest American Community Survey data, released last month, prepared by the Brookings Institution’s venerable demographer, Bill Frey. In a post entitled, “White neighborhoods get modestly more diverse, new census data show,” Frey looked at the racial and ethnic composition of the nation’s largest metropolitan areas, and gave us his first blush analysis of the unfolding trends of growing diversity and gradually receding racial and ethnic segregation.

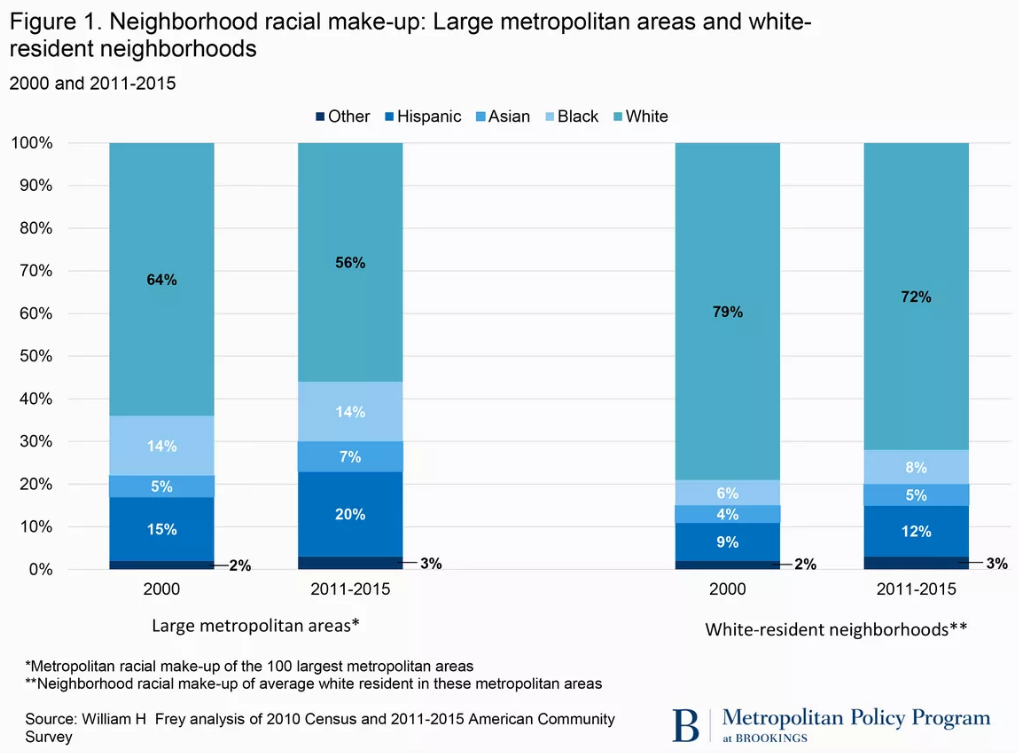

The big picture is that American metro areas are becoming more diverse. In the 100 largest metro areas, the share of the population that is white and non-Hispanic has declined from 64 percent in 2000 to 56 percent in 2011-15. And conversely the share that is Latino, Black, Asian or some other racial-ethnic category has increased from 36 percent to 44 percent. But while metro areas are becoming more diverse, the neighborhood in which the typical white resident lives is much less diverse than the overall metro area. In 2011-15, the typical white resident in a metro area lived in a neighborhood than was 72 percent white, down slightly from a level of 79 percent in 2000. In 2000, the average white resident lived in a neighborhood that has 15 percentage points (79% – 64%) more “white” than the metro area, in 2011-15, the typical white resident lived in a neighborhood than was 16 percentage points (72% – 56%) more white than the overall metro area.

Frey’s key point is that while America’s metro population is becoming increasingly diverse, especially with the growth of the Latino and Asian populations, most white Americans still live in neighborhoods that are disproportionately white, especially when compared to the overall racial and ethnic composition of the metropolitan area in which they are located. The best way to neatly summarize the complex relationship between neighborhood and metropolitan racial ethnic composition for this purpose is to look at the share of the population categorized as white at the metropolitan level, and then compare it the the share of the population that is white in the neighborhood in which the typical white resident in a particular metropolitan area lives. Statistically, by “typical” we mean median. Frey computes the share of the white population in the census tract in each metropolitan area which includes the population-weighted median white resident, with tracts sorted by white share of the population. Essentially, this means that half of the metro area’s white population lives in a tract with a white share of population higher than this “typical” number and half lives in a tract that has a white share of population lower than this number.

Of course, at City Observatory, we wanted to dig deeper. And Brookings and Frey have publicly posted their tabulation of the ACS data (you can download the spreadsheets here).

Metro versus neighborhood

A major factor influencing the demographic composition of the typical white neighborhood is the metropolitan area in which it is located. In more diverse metro areas, the typical white resident tends to live in a neighborhood with a smaller share of white population. We’ve plotted the relationship between the white share of the metropolitan area population (shown on the horizontal axis of the chart) against the share of the white population in which the typical white resident lives. The upward sloping line and strong correlation confirms that metro diversity influences neighborhood diversity.

You can think of the line as showing the typical relationship between the share of the population in a metropolitan area that is white and the average share of the population in a typical white neighborhood that is white. Metropolitan areas above that line have a higher fraction of whites in the typical white neighborhood than you would expect given their demographics, while metropolitan areas below the line are ones where the typical white resident lives in a neighborhood with a smaller share of white residents than you would expect, given the national pattern. So, for example, consider the difference between Portland and St. Louis. The two metro areas have a nearly identical share of white population (74 percent in St. Louis, 75 percent in Portland). But the average white St. Louis resident lives in a neighborhood that is 85 percent white, while the average Portland resident lives in a neighborhood that is 77 percent white. A second example: Memphis and Las Vegas have a similar share of white population (45 percent and 46 percent respectively). Yet the average white Memphis resident lives in a neighborhood that is 66 percent white, while the average Las Vegas white resident lives in a neighborhood that is 54 percent white.

Measuring the neighborhood effect

The difference between the overall share of the metro area population that is white and the white population’s share of the typical white neighborhood is a good indicator of the neighborhood effect: the extent to which the white population is segregated into neighborhoods that are whiter than the metro area itself. In effect, the difference between these two neighborhoods is an indicator of how segregated whites are from non-whites in the metropolitan area. If every census tract had the same white/non-white shares as the metropolitan area as a whole, there would be zero white/non-white segregation. (Notice that mathematically, the median share white in white census tracts cannot exceed the share white in the entire metropolitan area). In the following table, we rank metropolitan areas according to the difference in share white in the typical white neighborhood minus the metro area share that is white.

In the median large metropolitan area (for example Hartford, St. Louis or Charlotte), the typical white resident lives in a neighborhood that is about ten percentage points whiter than the metropolitan area as a whole. The places with the largest difference between the white share of the metro population and the white share of the typical white neighborhood include Miami, New York and Los Angeles, where white residents live in neighborhoods that are about 22 percent more white than the metropolitan area. The places with the smallest difference between the typical white neighborhood and the metro area average include Portland (2 percentage points), Pittsburgh and Salt Lake City (both about 4 percentage points).

The upshot is that when it comes to the lived experience of diversity, some factors are global, but important ones are still local. Its possible to live in a very diverse metropolitan area, with a high fraction of non-Hispanic white residents, and still have a high level of segregation, so that white residents live in places where they have very high levels of white neighbors. And the converse is also true, in some

Note

Throughout this commentary, we follow Bill Frey’s condensed version of Census Bureau racial and ethnic categories. By white, we mean persons who report to Census that they have a single race (white) and who report they are not of Hispanic origin. Frey’s report includes data for African-Americans and Asian-Americans who report a single race, persons of Hispanic origin, regardless of race, and a final category including all other persons. As we do regularly here at City Observatory, Frey reports data for metropolitan areas with a population of 1 million or more.