Portland’s Albina neighborhood was devastated by the I-5 freeway; Widening it repeats that mistake

Freeways and the traffic they generate are toxic to vibrant urban spaces. The great lesson of the urban freeway building boom of the 1960s was that it served chiefly to destroy, devalue and depopulate city neighborhoods throughout the nation. Freeways accomplished that in a variety of ways, first by demolishing homes and businesses for their right of way, then by flooding neighborhoods with traffic, and then further by facilitating flight to the suburbs. In essence, freeways re-prioritized urban spaces, not for the people who lived in them, but for the people who were traveling through them in automobiles. We now understand that facilitating car traffic degrades the urban environment, with predictable consequences for the health of city neighborhoods.

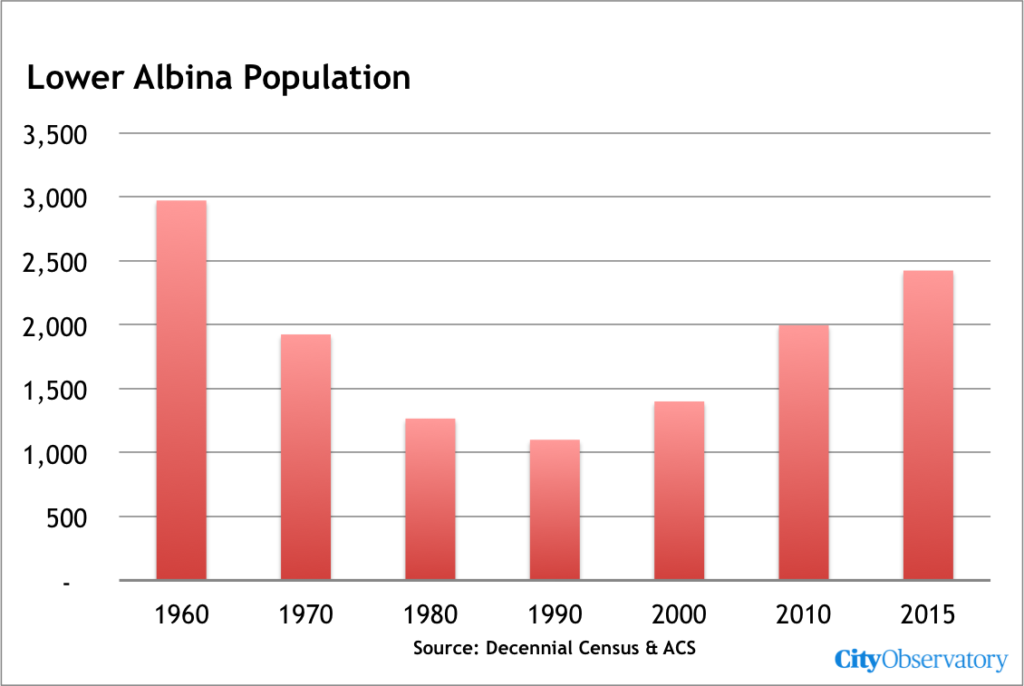

Nowhere was that process more apparent in Portland than in the Lower Albina neighborhood, which at the time was, thanks to racial segregation, the most significant concentration of African Americans in the state. In 1960, the Lower Albina neighborhood had a population of about 3,000 persons, about two-thirds of whom were black. In 1962, the Oregon State Highway Department carved Interstate 5 through the heart of this neighborhood and through North Portland, and directly demolished more than 300 homes, which it did not replace. But the indirect effects of the freeway, and its attendant traffic were equally, if not more devastating. By injecting a flood of cars into the area, the freeway led to the collapse of the local neighborhood.

Just as elsewhere, freeway expansion and increased car traffic killed neighborhoods and crippled cities. In the aftermath of freeway construction, I-5 turned the Albina neighborhood from houses and shops to a collection of car dealers, gas stations and parking lots. Humans were replaced as the dominant life form by metal boxes. This was obvious even at the time, as James Marston Fitch wrote in The New York Times in 1960:

The automobile has not merely taken over the street, it has dissolved the living tissue of the city. Its appetite for space is absolutely insatiable; moving and parked, it devours urban land, leaving buildings as mere islands of habitable space in a sea of dangerous and ugly traffic.

The impact of freeway construction here is similar to what has been found across the United States: freeway construction kills urban neighborhoods. In a detailed study of the effect of freeway construction on city population, Professor Nathan Baum-Snow found that each additional radial freeway constructed through a city reduced the city’s population by 18 percent. As Jeff Speck put it in a recent speech in Houston, “Highway investment is the quickest path to devaluing the inner city.”

Wholly Moses: Taking a Meat Axe to the City

This, as the saying goes, was no accident. The original route of the Interstate 5, which at the time was called the “Eastbank Freeway” was recommended by none other than Robert Moses, who came to Portland in 1943 with a group of his “Moses Men,” to recommend a public works program for the region, which consisted at its core, of recommendations that the city be carved up by a series of freeways, beginning with one on the east bank of the Willamette River. Freeways, Moses said “. . . must go right through cities, and not around them, . . . When you’re operating in an overbuilt metropolis you have to hack your way with a meat axe.” (Moses, 1954, quoted in Mohl, 2002).

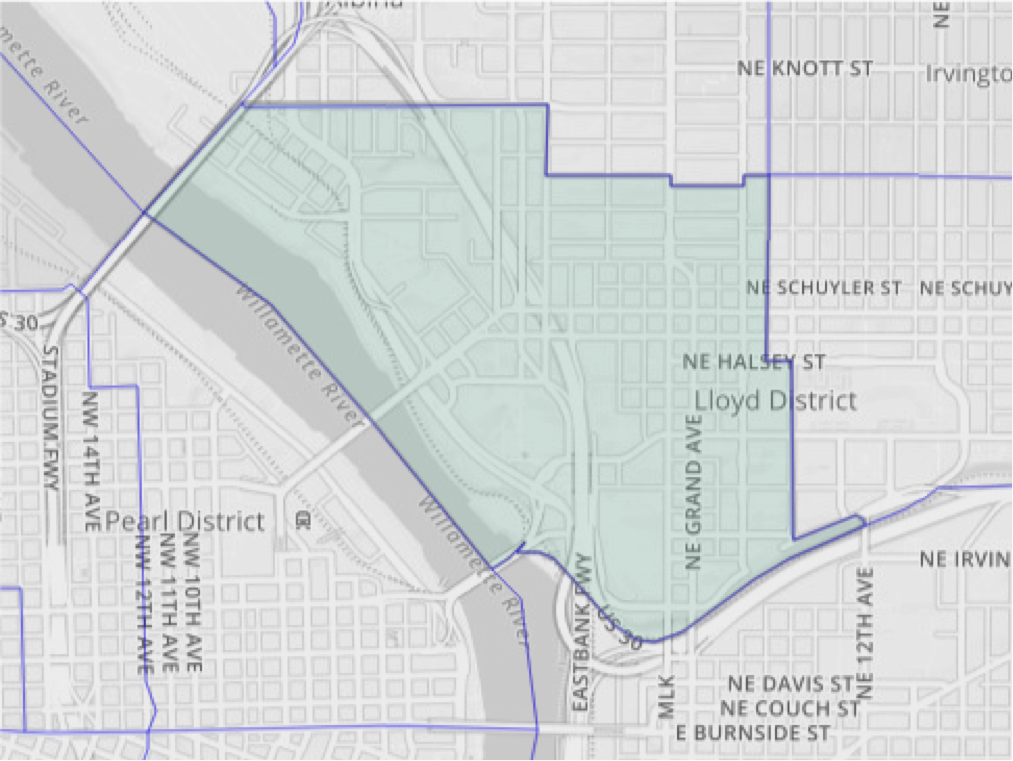

Building the freeway clearly privileged the interests of those driving through the area, especially suburban commuters, over the people who actually lived here. The onslaught of demolitions led to a decline in business, a loss of the community’s economic and social critical mass, and triggered a long period of decline in Lower Albina. That’s clear when we look at what happened to the Albina neighborhood in the years after the freeway was completed. Here we focus on Census Tract 23.03, an area that closely corresponds to the project impact area of the proposed Rose Quarter Freeway widening project. Tract 23.03 runs from the southernmost ramps of Interstate 5 as it connects to the Fremont Bridge on the North to Interstate 84 on the South, and includes the area lying between the Willamette River and Williams Avenue.

In the 1960s and earlier, this area was classified by the Census Bureau as two different Census Tracts, 22.02 and 23.02. Tellingly, the two tracts were subsequently consolidated due to sustained population losses. We’ve created a harmonized set of population estimates for the period 1960 to 2015 by linking these two different definitions. Notice that the Census Bureau’s map still refers to I-5 in this area as the “Eastbank Freeway”–an anachronistic appellation that dates back to Moses’ 1940s freeway plan for Portland.

In 1960, which was actually after the completion of the Memorial Coliseum, this area still had a population of almost 3,000. By 1970, just eight years after freeway construction, population declined by a third. Over the next decade, population declined even further, and by 1980 population had declined by another third. In the two decades following construction of the I-5 freeway through lower Albina, more than 1,700 persons were displaced from this neighborhood.

Neighborhood decline continued through 1990, when population in tract 23.03 bottomed out at 1,100 persons–barely one-third of its 1960 level. Since then, population has begun to rebound, and has grown.

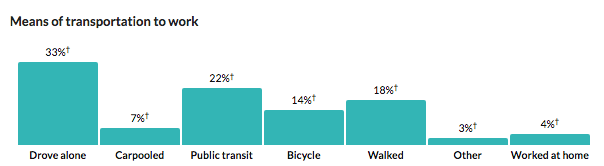

What’s remarkable about the growth of the neighborhood is that it has attracted people who have chosen to live in a much more sustainable fashion than the average Portland resident. Census Tract 23.03 is one of handful of neighborhoods in the Portland metropolitan area in which a majority of residents commute to their jobs by transit, walking and cycling. Only about a third of residents drive alone to work. Just as was the case with the initial construction of Interstate 5, the freeway widening project again privileges the interests of those passing through the neighborhood (providing more travel lanes and rearranging local streets to more quickly move cars on and off the freeway), over the interests of local residents.

Source: Census Bureau, American Community Survey, via CensusReporter

Source: Census Bureau, American Community Survey, via CensusReporter

It has taken four decades to begin to reverse the decline, and now ODOT is planning to delivery a fresh dose of cars. Public relations messaging to the contrary notwithstanding, the Rose Quarter “Improvement” Plan, plainly prioritizes cars and disadvantages people walking, biking, taking transit, or just hanging out on the streets of this neighborhood.

Take just one detail–the radius of curvature at major intersections. All over the city, were spending public dollars to “bump out” the corners of intersections, to shorten crossing distances for people on foot, and to slow turning cars, and make pedestrians more visible. Here, we’re doing just the opposite, carving away walking space to create shorter, faster turns for those in automobiles. That decision speaks volumes about the true priorities this project has. Car movement trumps people. We’re building an environment that privileges the vehicles of those moving through it over the people who are choosing to be in it.

People and investors are hardly blind to the pecking order in these places. A streetscape dominated by lots of fast moving cars is not one where people will linger, or the kinds of businesses–like restaurants, cafes and interesting shops–will set up shop.

Just as this neighborhood is getting back on its feet, ODOT is once again proposing a massive freeway project that will remake the neighborhood, chiefly to the benefit of car travelers. The freeway will be physically widened, it is virtually certain to induce more traffic. In addition, as we’ve pointed out at City Observatory, the footprint of the project allows ODOT to have eight full-sized travel lanes on the freeway, just by striping it to the same standards it already uses in urban interstate freeways in Portland. That, combined with pedestrian-hostile high speed corners and a miniature diverging-diamond interchange–which puts fast moving car traffic on the wrong (left) side of two way streets, it’s just a kind of passive-aggressive 21st century way to mold urban space in a way that prioritizes cars over people. This effort may have slicker PR, but the message is the same: this place is for cars. History has taught us what that kind of priority means for city neighobrhoods.