The Transportation Research Board, nominally an arm of the National Academy of Sciences, is engaged in technocratic climate arson with its call for further highway expansion and more car travel.

- The planet is in imminent peril from global warming, with much of the recent increase in emissions in the US coming from increased driving.

- In the face of this monumental crisis, the Transportation Research Board, which should represent science, is calling for tripling spending on highway construction to as much as $70 billion annually, to accomodate and another 1.25 trillion miles of driving each year.

- They’re ignoring global warming (except as an excuse to flood-proof highways), and hoping that somebody else electrifies cars, so that carbon emissions go down.

- No consideration is being given to how we might reduce driving to reduce pollution, and make our cities–which were devastated by the construction of the interstate highways—more livable, green and just.

At City Observatory, we think climate change is the challenge of our time. One of the biggest opportunities to meet this crisis is to dramatically rethink the way we get around and the way we build our cities. The interstate highway system and the car-centric transportation system and land use patterns it fostered have undermined our cities, torn our civic fabric, segregated our citizens and threaten our environment. Much of what is happening today in urbanism is a wave of experiments aimed at reversing the damage done by cars and highways. It’s a project of collective remembering that great urban places are walkable, bikeable and well-served by transit, bringing us closer together and freeing us from our dependence on cars and their substantial costs, pecuniary, social and environmental.

If we’re serious about tackling climate change, reversing the damage done by the Interstate Highway system should be at the top of our list. A new congressionally mandated review of the system provides, in theory, an opportunity to think hard about how we might invest for the kind of future we’re going to live in. Sadly, the report we’ve been provided by the Transportation Research Board is a kind of stilted amnesia, which calls for us to repeat the today just what we did 70 years ago. Now is no time for indulging nostalgia for the Eisenhower era. But that’s exactly what we’re being offered.

The new report looks at the future of the Interstate Highway System, and calls for spending hundreds of billions of dollars expanding interstates and to facilitate more than a trillion miles of additional driving every year. The report comes from the Transportation Research Board, which is part of the National Academies of Engineering and is affiliated with the National Academy of Sciences. The report was overseen by the “Committee on the Future Interstate Highway System,” and written by TRB staff and consultants.

While much of its work is prosaic and uncontroversial (coming up with standards for paving materials and road markings, and figuring out how to optimize traffic signals), some of the Transportation Research Board’s work has a profound and subtle bias that is at the root of our urban transportation problems.

In the past we’ve written about how engineering “rules of thumb“–minimum parking requirements for buildings, minimum lane widths for roads, “level of service” traffic standards, and hierarchical, dendritic street systems–systematically lead to less livable, more car-dependent communities. While its ostensibly a technocratic exercise, the new report titled “Renewing the National Commitment to the Interstate Highway System: A Foundation for the Future” is really a strongly political statement in favor of more and more road building. The title clearly signals the messaging: this is a backward looking plea for funds, asking us to repeat what we did in the past.

And even if you didn’t read the title, The cover illustration pretty much gives away the game: This is all about rationalizing building more highway capacity.

Climate Change: That’s someone else’s problem

There’s an overwhelming consensus in the scientific world that anthropogenic climate change is rapidly reaching irreversible and catastrophic proportions. The International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has issued a dire warning that we have just a little over a decade to save the planet.

If you wade through the first 118 pages of the TRB report, you’ll finally reach a mention of climate change. A short sidebar (Box 4.2) concedes that by stimulating vehicle use and car-dependent travel problems the Interstate Highway System contributed to the problem. And the solution is to . . . wait for somebody else to develop low-carbon and no-carbon transport technologies:

. . . a transformation to a low- and no-carbon transportation system will increasingly mean that [freeway] planning is integrated with the planning of low-carbon mobility options, from public transit to zero-emission trucks. Many states, counties, and cities are investing in low-carbon transportation solutions, seeking to create new opportunities for both low-carbon mobility and economic development.

The report acknowledges the reality of climate change, but largely ignores and minimizes the contribution of vehicle travel to carbon emissions. Instead, the report is chiefly concerned about using climate change as yet another excuse to spend more money on rebuilding highways (to harden them against flooding, storms and other climate-related disruptions). In essence the report paints highways (and highway department’s distressed budgets) as victims of climate change, rather than one of its principal causes.

We’re told that the Interstate Highway System accounts for a mere 7 percent of US greenhouse gas emissions. That of course misses the fact that in many states, highway travel accounts for 40 percent of greenhouse gas emissions, and unlike other sources of carbon pollution, it is increasing—for example, causing both Oregon and California to lose ground on their climate change objectives.

More importantly, the Interstate Highways make all of us more car dependent, whether we travel on the Interstate or not. As the report acknowledges–grudgingly, and in passing–the toll the Interstate system wreaked on cities.

It is generally understood that urban Interstates and other freeways contributed to suburbanization and the depopulation of many major U.S. cities, which accelerated after World War II in concert with an expanding middle class and the fast-growing personal motor vehicle fleet. Although many other factors were at work, the Interstate System facilitated greater dependence on the automobile for commuting to work and other household and social activities.

However, the effects of urban Interstates were not entirely beneficial for center cities and their neighborhoods. The postwar mass movement of people and employers to the suburbs led to the loss of center city population, a declining housing stock, and impoverished urban neighborhoods (TRB 1998).

“Not entirely beneficial” is perhaps the most banal way of conceding the fact that highways devastated cities and amplified segregation, problems that plague us today. Nathan Baum-Snow has estimated that each additional radial freeway constructed in a metropolitan area reduced the central city’s population by 18 percent.

One has to be very resolute in overlooking all of the negative consequences of increased car dependence wrought by the interstate highway system, in the form of sprawl, the deaths and injuries (especially to vulnerable non-car road users) pollution, and the destruction of urban neighborhoods. Allusions to the supposed economic benefits of the original interstate highway system in the 1950s and 1960s (which benefitted the trucking industry and suburban land developers to be sure), are not something that would be repeated by additions to the system in the 2020s and beyond. The careful scholarship on road investments has shown that the economic return on investment from additional highway capacity has fallen to almost zero in the past several decades. And that doesn’t allow for full accounting of the social, environmental and health effects of car dependence.

TRB’s Vision: One and a quarter trillion more miles of driving annually by 2040

The case for “renewing” our commitment to expanding the Interstate Highway System is predicated on forecasts of increased driving activity. While the report is careful to couch its findings in technical terms and talk about the smallest possible numeric increments (1.5 percent per year), the implications of their traffic projections are for a huge increase in the volume of driving. At their mid-range figure 1.5 percent per year of 1.5 percent annual growth, vehicle miles traveled in the US will increase by about one and a quarter trillion miles annually by 2040, up from about 3.2 trillion today to nearly 4.5 trillion in 2040.

The climate implications of all that driving? Not TRB’s problem. Automakers or somebody might electrify vehicles, and reduce carbon emissions, but that’s not something that highway engineers are going to worry about–at all.

It’s worth questioning whether that 1.5 percent annual increase makes any sense. The report and its technical appendix is careful to hedge its forecasts with all kinds of qualifications about the economic and technological uncertainty of predicting future travel patterns, but when it comes down to it, they conclude that come hell or high water (and what with global warming, it’s likely to be both), traffic will only go up, somewhere between .75 percent annually and 2 percent annually.

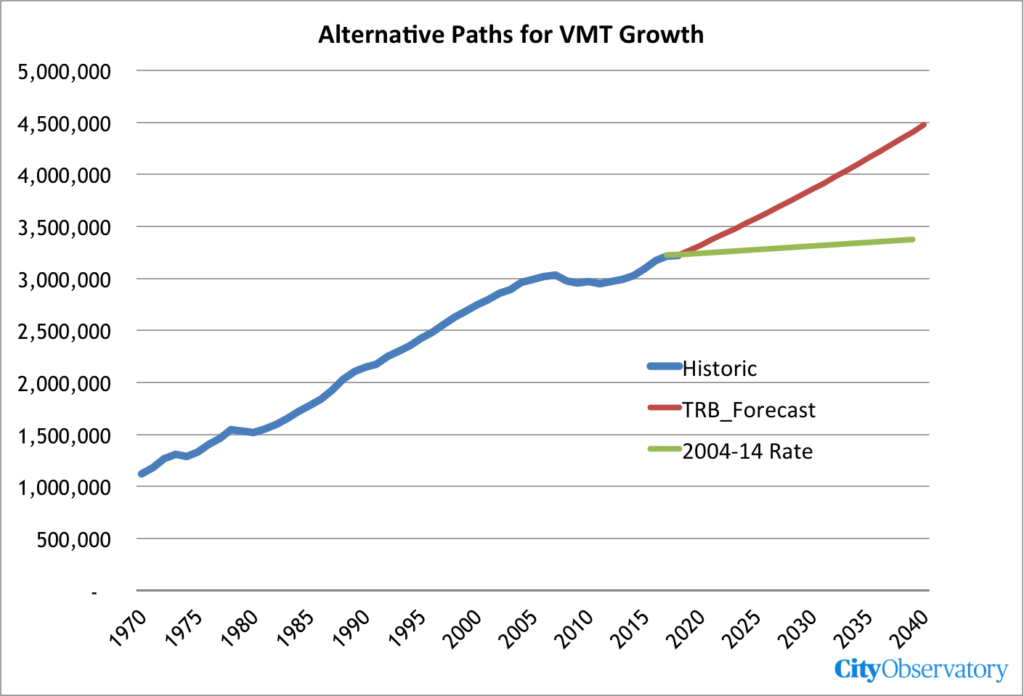

A quick review of recent trends in driving is in order. The key metric here is “vehicle miles traveled. Last year Americans drove about 3.2 trillion miles, according to the US Department of Transportation. The following chart shows the trend in VMT since 1970, with actual values in blue, the TRB’s baseline forecast in red, and an alternative lower forecast (which we’ll explain in a moment, in green). The long term trend, particularly from the 1970s until the turn of the millennium was for a steady increase in driving year over year, but after 2000 things began to change.

At first the rate of increase slowed and then declined; from 2004 through 2014 per capita vehicle miles traveled actually declined. For economists, this was hardly a surprise: real fuel prices increased dramatically after 2004, and remained high through 2014; it was only after the oil market bust that year that driving started going up. Interestingly the growth rate for the four years 2014 to 2018 was slightly more than 1.5 percent, the exact figure that TRB forecasts to continue for the next two decades. Implicitly, TRB is assuming that driving will grow for the next 20 years or so at the same pace that it managed (a) after a decade of stagnation, and (b) over a period of time in which real fuel prices fell by more than 40 percent.

The experience of 2004 to 2014 suggests that a very different future is entirely possible. Somewhat higher gas prices—high enough to reflect the social and environmental cost of carbon—are likely to depress if not entirely eliminate the growth in VMT. If we changed gas prices to resemble the 2004-14 period, we would expect driving to increase only very slowly, as shown in the green line. The experience of the past decade shows that its extremely possible for the US to have a much slower rate of increase in driving. All it takes are the right policies.

And increasingly, policies that discourage driving will be essential to saving the planet. As economists of every political stripe have stressed, some sort of carbon tax is essential to lowering carbon emissions—plus they’ll have the side benefit of lowering the need to build extremely expensive highway infrastructure. An intelligent report would consider how the US could, building on the experience of leading cities and other countries, work to build communities that simply require less driving, thereby reducing carbon pollution, lowering road costs, and not incidentally, mitigating some of the historic damage done to cities by the construction of the interstate highway system.

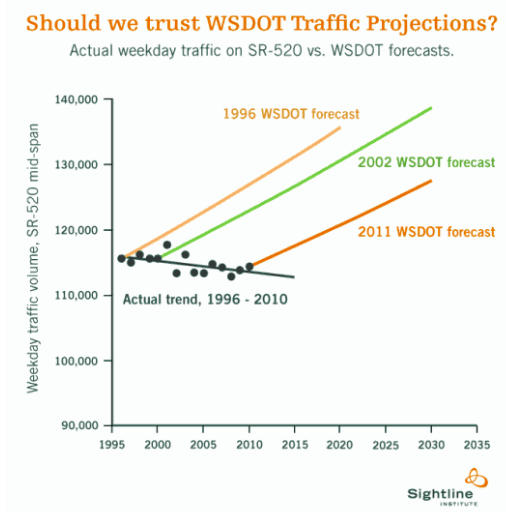

The upward slope of that red line and the added trillion miles we’re assumed to drive each year is the oldest trick in the highway engineer’s book. “More cars are coming! It’s an inexorable, immutable force that we must respond to. We must expand capacity.” But these forecasts have been repeatedly shown to be wrong. For example, Clark Williams-Derry exposed the serial misrepresentation by the Washington Department of Transportation:

The engineers routinely ignore or grossly downplay the effects of induced demand—that the principal reason that driving is increasing is that we’re building vastly more un-priced road capacity. More road capacity, generates more sprawl, longer trips and more VMT, in a never-ending, self-reinforcing cycle, one which is now so well established as to be called the “fundamental law of road congestion.”

If we build highways for another trillion miles of vehicle travel we’re actively making the carbon pollution problem worse, not, as engineers would have it, passively responding to some unchanging natural trend. If Americans drive a trillion more miles each year by 2040, it’s going to make it vastly more difficult to reduce greenhouse gases. Failing to acknowledge that fundamental fact, and suggesting a casual mention of vehicle electrification absolves them of any responsibility for thinking further about this question is simply irresponsible.

Same old punchline: Give us billions more

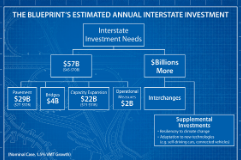

As Chuck Marohn of StrongTowns has pointed out, reports by engineering groups are almost invariably self-serving demands for more money thinly disguised as impartial technical advice. Not surprisingly, the TRB report’s primary recommendation is that we give more money to highway builders—lots more money. The report calls for doubling to tripling the amount of money spent on Interstate highways:

Recent combined state and federal capital spending on the Interstates has been about $20–$25 billion per year. The estimates in this study suggest this level of spending is too low and that $45–$70 billion annually over the next 20 years will be needed

And a big chunk of this funding would be for explicitly earmarked for capacity expansion. The report is vague, but its “blueprint” says $22 billion of a $57 billion pot would be set for capacity expansion, with the remainder for pavement, operations and bridges (categories that are often used to fund wider roadways—bridges that are “rebuilt” are almost invariably widened).

While the report talks a good game about aging bridges and multiplying potholes, there’s abundant evidence that when additional revenue is available, maintenance is still deferred in favor of marquee capacity expansions. State Departments of Transportation (who are allocated the bulk of money for the interstate system) have repeatedly engaged in bait and switch tactics; marketing potholes and spending on wider roads.

This is a report that looks backward, learns nothing, and is destined to repeat the mistakes of the past, while remaining obstinately blind to the manifest threat that climate change poses to our collective global future. Now is not the time to be squandering precious billions on more and wider roads, and stimulating trillions of additional miles of vehicle travel. This report tragically evades the most serious problem we face and avoids shouldering any responsibility for meaningful action. It’s difficult to imagine that anything so willfully narrow-minded and self-serving could be allowed to masquerade as the product of scientific endeavor.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2019. Renewing the National Commitment to the Interstate Highway System: A Foundation for the Future. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25334.