More evidence that supply and demand are at work in housing markets

In early 2016, Portland experienced some of the highest levels of rent inflation of any market in the US. According to Zillow’s rental price estimates, rents were rising between 15 and 20 percent year over year in late 2015 and early 2016. Portland was attracting lots of new residents, and its housing supply was still in the process of rebounding from the effects of the Great Recession. In response to the big uptick in rents, the city enacted one of the nation’s most stringent inclusionary zoning requirements, which will force developers of new apartment buildings permitted after February 2017 to set aside as much as 20 percent of new units for low and moderate income households.

But in the past year, there are growing signs that the surge in rental inflation has peaked. According to Zillow’s estimates, the average price of a two-bedroom apartment in the Portland area $1495 is almost exactly the same as it was a year ago. Rental price inflation has dropped from nearly 20 percent a year ago to effectively zero in the first few months of 2017.

It’s not easy to accurately estimate the current level of apartment rents. Different sources have their own strengths and limitations, and some services, which just rely on skimming the current crop of apartment listings, with little adjustment for quality or time on market, produce erratic and unreliable results, as we’ve explained. So to try and triangulate our view of the Portland market, we turn to a couple of other sources of information.

Zillow’s estimates of current rent price inflation are largely confirmed by independent figures from ApartmentList.com. ApartmentList.com uses a variant of the “repeat sales” technique employed by the CaseShiller home price index. By comparing the rental price for the same apartment at different periods of time, one can generate estimates of price inflation that are unaffected by shifts in the composition of apartments available for rent at different times (a problem that plagues more simple-minded indices). ApartmentList.com’s estimates suggest that Portland’s rents have fallen to 0.9 percent in the past twelve months.

In its national rankings, ApartmentList.com now ranks Portland one of seven markets with declining rents over the past year, a group that includes Houston, San Francisco, and Miami. The following chart shows 12 month rent inflation estimates for each of the nation’s 52 largest metropolitan areas.

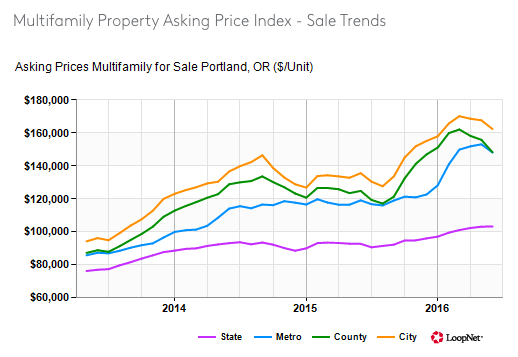

Another bellwether of the multi-family marketplace, asking prices for apartments seems to have peaked and declined slightly in the past few months. LoopNet, which tracks real estate transactions, reports that the asking price for apartments for sale has declined about 4 percent in the past few months. These data suggest that investors, who bid up the typical price of an apartment to almost $170,000 in 2016, have backed off a bit from that level. (The amount that investors are willing to pay for apartments tracks closely with expectations about future rent levels).

The outlook: Higher incomes, more housing supply

Going forward, there are a couple of reasons to expect that Portland’s housing affordability problems will moderate. First, the improving regional economy is starting to drive up incomes. State economist Josh Lehner has an analysis showing that renter incomes are rising, and predicts that rental affordability (as measured by the share of income that people spend on rent) will stop getting worse.

More importantly, there’s a big surge in apartment supply in Portland. One private firm that tracks the construction industry locally–the Barry Apartment Report–estimates that there are roughly 25,000 apartments in the construction pipeline in Portland.

The big uncertainty in the years ahead will be whether the policies the city has enacted (inclusionary zoning) and others that it is considering (rent control) will choke off future investment in local housing supply. Once the current inventory of permitted housing is built (and much of it was permitted just prior to the new inclusionary requirements taking effect), its far from clear that developers will find Portland as attractive a marketplace for new apartments as it has been in the past few years.