If you’re serious about dealing with climate change, the last thing you should do is spend billions widening freeways.

April 22 is Earth Day, and to celebrate, Oregon is moving forward with plans to drop more than a billion dollars into three Portland area freeway widening projects. It isn’t so much Earth Day as a three-weeks late “April Fools Day.”

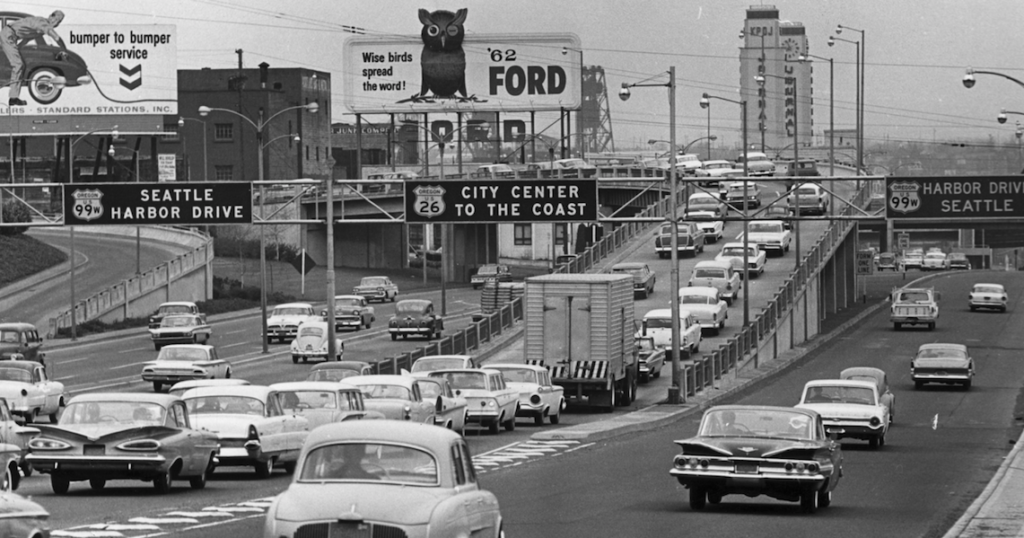

Four decades after the city earned national recognition for tearing out a downtown freeway, it gets ready to build more. Back in the day, Portland built its environmental cred by tearing out one downtown freeway, and cancelling another–and then taking the money it saved to build the first leg of its light rail system. In place of pavement and pollution, it put up parks. Downtown Portland’s Willamette riverfront used to look like this:

Now the riverfront looks like this:

But as part of a transportation package enacted by the 2017 Oregon Legislature, higher gas taxes and vehicle registration fees will be used partly to shore up the state’s multi-billion dollar maintenance backlog, but prominently to build three big freeway widening projects in the Portland metropolitan area. One project would spend $450 million to add lanes to Interstate 5 near downtown Portland, two others would widen freeways in the area’s principal suburbs. The estimated cost of the projects would be around a billion dollars, but when it comes to large projects, the Oregon Department of Transportation is notorious for grossly underestimating costs. Its largest recent project, widening US Highway 20 between Corvallis and Newport was supposed to cost a little over $100 million but has ended up costing almost $400 million.

The plan flies in the face of the state’s legally adopted requirement to reduce greenhouse gases. Just last year, the state’s Greenhouse Gas Commission (of course, Oregon has one) reported that the state is way off track in achieving its statutorily mandate to reduce greenhouse gases by 10 percent from their 1990 levels by 2020. The commission’s finding:

Key Takeaway: Rising transportation emissions are driving increases in statewide emissions.

As the updated greenhouse gas inventory data clearly indicate, Oregon’s emissions had been declining or holding relatively steady through 2014 but recorded a non-trivial increase between 2014 and 2015. The majority of this increase (60%) was due to increased emissions from the transportation sector, specifically the use of gasoline and diesel. The reversal of the recent trend in emissions declines, both in the transportation sector and statewide, likely means that Oregon will not meet its 2020 emission reduction goal. More action is needed, particularly in the transportation sector, if the state is to meet our longer-term GHG reduction goals.

In Oregon, as in many states, transportation is now the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, and cheaper gas is now prompting more travel. The decline in gasoline prices in mid-2014 prompted an increasing in driving and with it, an increase in crashes and carbon pollution. Oregon’s vehicle miles traveled, which had been declining steadily, ticked up in 2015, as did its fatality rate. Building more freeway capacity–which will trigger more traffic–flies in the face of the state’s stated and legislated commitment to reducing greenhouse gases.

Building more capacity doesn’t solve congestion, it just increases traffic (and emissions)

The new word of the day is bottleneck: Supposedly, adding a lane or two in a few key locations will magically remedy traffic congestion. But the evidence is always that when you “fix” one bottleneck, the road simply gets jammed up at the next one. As the Frontier Group has chronicled, the nation is replete with examples of billion dollar boondoggle highways that have been sold on overstated traffic projections, and which have done little or nothing to reduce congestion.

As we all know, widening freeways to reduce traffic congestion has been a spectacular failure everywhere its been tried. From the epic 23-lanes of the Katy Freeway, to the billion dollar Sepulveda Pass in Los Angeles, adding more capacity simply generates more traffic, which quickly produces the same or even longer of delays. The case for what is called induced demand is now so well established that its now referred to as “The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion.” Each incremental expansion of freeway capacity produces a proportionate increase in traffic. And not only does more capacity induce more demand, it leads to more vehicle emissions–which is why claims that reducing vehicle idling in congestion will somehow lower carbon emissions is a delusional rationalization.

If you’re a highway engineer or a construction company, induced demand is the gift that keeps on giving: No matter how much we spend adding capacity to “reduce congestion,” we’ll always need to spend even more to cope with the added traffic that our last congestion-fighting project triggered. While that keeps engineers and highway builders happy, motorists and taxpayers should start getting wise to this scam.

A Faustian bargain for transit and active transportation

Portland’s freeway widening proposal was part of a convoluted political bargain to justify spending for a proposed light rail line. Supposedly, voters won’t approve funding for new transit expansion in Portland unless its somehow “bundled” with funding for freeway expansion projects. That flies in the face of experience of other progressive metropolitan areas, including Denver, Los Angeles and San Francisco. Urban transit finance measures have a remarkable 71 percent record of ballot box success. Just last November, voters in Seattle approved a $54 billion (that’s with a “B”) Sound Transit3 tax measure to fund a massive, region-wide expansion of bus and rail transit. To argue that you can’t get public support to fund transit with out also subsidizing freeways is an argument that’s at least 50 years out of date.

The good news is that there’s some pushback from folks who think more freeways isn’t a solution to anything. But a lot of the energy seems to be directed to a “me too” package of investments in token improvements to biking and walking infrastructure. As Strong Town’s Chuck Marohn warns, that’s a dead end for communities, the environment and a sensible transportation system; while he’s writing about Minnesota, the same case applies in Oregon:

Oh, they’ll pander to you. They’ll promise you all kinds of things….fancy new trains (to park and rides), bike trails (in the ditch, but not safe streets)….but this system isn’t representing you at all. It’s on autopilot. It’s got a long line of Rice interchanges and St. Croix bridge projects just ready to go when you give them the money. Don’t do it.

And as a final word, for those of you hoping to fund transit, pedestrian and cycling improvements out of increased state and federal dollars, I offer two observations. First, you are advocating for high-return investments in a financing system that does not currently value return-on-investment. You are going to finish way behind on every race, at least until we no longer have the funds to even run a race. Stop selling out for a drop in the bucket and start demanding high ROI spending.

Second, the cost of getting anything you want is going to be expansive funding to prop up the systems that hurt the viability of transit, biking and walking improvements. Every dollar you get is going to be bought with dozens of dollars for suburban commuters, their parking lots and drive throughs and their mindset continuing to oppose your efforts at every turn. You win more by defunding them than by eating their table scraps.

So when it comes to 21st Century transportation and Earth Day, maybe we should start with an environmental variation on the Hippocratic Oath: “First, do no harm.” We were smart enough to stop building freeways when environmentalism was in its infancy, and the prospects of climate change were not nearly so evident. Why aren’t we smart enough to do the same today?