Ah, Paris! Perhaps one of the world’s most beautiful cities, a capital of European culture, and prosperous economic hub. What’s its secret? Zoning, of course!

Just kidding. Actually, Paris went for the better part of a millennium (until 1967) with nothing that an American might recognize as district-based zoning, a prospect that would surely horrify the planners who have been one-upping not just Paris, but pre-zoning American neighborhoods from brownstone Brooklyn to Midtown Memphis, with postwar sprawl for the last several generations.

Today, we live in cities and neighborhoods where zoning has made the kinds of places we used to take for granted, and that still make up some of our most prized communities, illegal to build. These laws are so pervasive that even relatively small changes are considered radical, experimental, and potentially dangerous methods of social engineering. Partly, that’s because we ignore the lessons in our own cities about what works in neighborhoods built before modern zoning. But it also may have something to do with the fact that our conversations about urban planning tend to be hyper-local: we might try to take cues from other neighborhoods, or another city in our region—or maybe another American city several states away. But even many big-time urban wonks would be hard pressed to tell you much about how cities in other countries do it.

Which is just one reason why Zoned in the USA, a book published by Virginia Tech’s Sonia Hirt last year, is so valuable. An entire section is dedicated to describing the zoning and planning processes of countries from Sweden to Australia, and contrasting them to the American system. It’s absolutely worth reading the entire book—including for her arguments about the origins of American zoning, which seek to modify the property-value-based ideas put forward by writers like William Fischel in The Homevoter Hypothesis—but in the meantime, here are some big conclusions about how foreign zoning is different from our own.

1. The single-family-only district is not king

Hirt’s major claim is that what really sets American zoning apart is its orientation, explicit or implicit, to putting the single-family residential zone at the top of the hierarchy of urban land uses. Not only are single-family zones listed first in many zoning codes, but they make up significant pluralities, or even majorities, of total land area in most American cities. Interestingly, Hirt points out that this wasn’t necessarily true when zoning was first introduced: New York’s famous first zoning law didn’t even have a single-family zone at all.

Cities in other countries remain closer to our origins, then. In Great Britain, for example, local development plans generally set limits on residential density by the number of housing units per given land area, rather than dictate the form that those housing units must take. In the Paris area, too, land use intensity is determined by something like FAR, or the ratio of total floor area to lot area, rather than prescribing apartments or detached homes. The German zoning system, which in some ways appears very similar to ours, does not even have a single-family category.

As Hirt points out, Americans appear to be unique in believing that there is something so special about single-family homes that they must be protected from all other kinds of buildings and uses—even other homes, if those homes happen to share a wall. The recent revolt in Seattle over a proposal to soften that city’s single-family districts, in other words, would not be possible anywhere else in the world, not least because very few people live in single-family districts to begin with.

2. “Residential” doesn’t mean what we think it means

Not only do other countries lack single-family zones, or at least use them much, much more rarely, but the separation of residential from other uses is much softer. Whereas placing a shop in the middle of a residential block would be counter to the very purpose of an American “residential” zone, it’s considered an essential part of neighborhood planning elsewhere.

The “residential protection sector” zone in Paris, for example, allows a certain percentage of buildings to be used for non-residential uses, as long as they don’t create “nuisance.” In Germany, the “small-scale residential” and “exclusively residential” zones—the lowest-density residential designations possible—actually allow a range of retail and other uses as of right. The general principle is that businesses that serve everyday neighborhood needs, like small bank branches, corner stores, or medical offices, ought to be allowed within walking distance of people’s homes. Bigger uses that might attract more regional traffic are separated out. And in Sweden, although amendments (or what we might call “variances”) are needed to place a shop or other commercial use in a residential district, such amendments are regularly granted.

3. State and national law is as important as local

In the U.S., states generally have something called a zoning enabling act, which gives municipalities the legal authority to regulate land use through zoning. But these enabling acts tend to be extremely loose in terms of dictating what that land use should look like: the principle here is that planning ought to be done as locally as possible.

In many other rich countries, however, national and state or provincial governments play a much stronger role in urban planning. In Great Britain, the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act sets land use guidelines nationally; local communities are required to create their own land use plans, but using a pre-determined set of categories. Unlike American cities, then, British ones cannot invent their own ultra-exclusionary zones. Even next door, Canada gives its provinces significant power to set the framework of local zoning, resulting in very different systems from one province to the next.

That may offend American ideals about local autonomy. But it also helps prevent some of the problems with hyper-local decision-making, including the tendency for neighbors to use zoning to exclude the kinds of people they don’t want: most often the low-income, or people of color. How to combat that tendency has become one of the central challenges for American housing policy, as evidenced by the recent high-profile Supreme Court case on the Fair Housing Act and the Obama Administration’s new, more aggressive rules around affirmatively furthering fair housing.

4. There are other ways to plan

So zoning laws abroad tend to more flexible and permissive than their American counterparts, which means that many of the things we’ve outlawed here—like a mix of single-family homes and apartments in the same neighborhood, creating homes that are sized and priced appropriately for a diverse range of people; or having local businesses integrated within walking distance of where people live—are still legal in the rest of the industrialized world.

But Hirt points out that this doesn’t mean that other countries necessarily have a more laissez-faire approach to urban planning, letting private actors run wild over the visions that residents have for their communities and cities. Rather, other countries have a broader range of tools at their disposal to shape how their cities work and feel. In the Netherlands, for example, the government purchases land at the edge of a metropolitan area and then uses that ownership to manage the growth of the region. That and other kinds of public ownership, or more aggressive tax and subsidy policies, allows many other wealthy countries to direct their cities’ growth, and meet planning goals, without the kind of limiting prescriptions on land use that prevent our postwar neighborhoods from recreating what works about pre-zoning neighborhoods, while fixing what doesn’t.

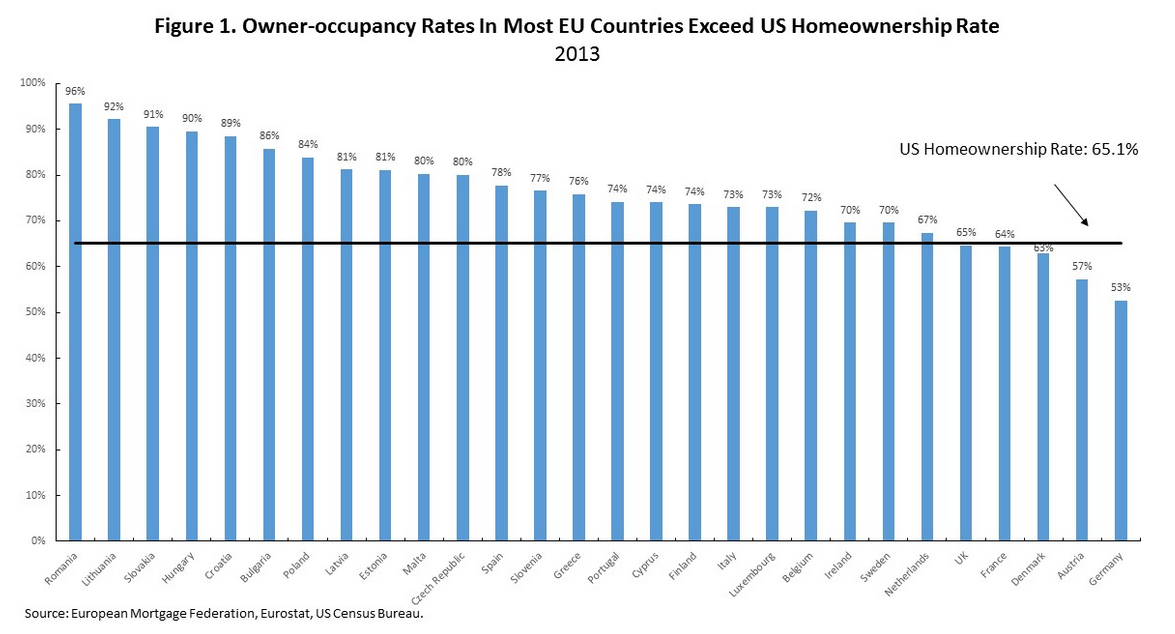

Of course, the U.S. can’t, and shouldn’t, just ape other country’s systems; there are very different urban histories and values here that ought to be respected. But it’s worth pointing out that one of the biggest ones—the ideal of homeownership—is actually less uniquely American than we often suppose. In fact, many of the European countries mentioned in this article have higher levels of homeownership than the U.S., even though their land use systems don’t prioritize the homogeneous single-family neighborhood to nearly the extent that we do, or at all.

As we recognize the ways that our neighborhoods and cities could be improved, then—by encouraging less segregation by income and race; reducing travel times by bringing destinations closer together; encouraging more walking and physical exercise; and creating more public places where people can gather and build community—it seems only reasonable to look at what’s different in the places that may do some of those things better.