Drawings don’t constitute restorative justice

ODOT shows fancy drawings about what might be built, but isn’t talking about actually paying to build anything

Just building the housing shown in its diagrams would require $160 million to $260 million

Even that would replace only a fraction of the housing destroyed by ODOT highway building in Albina

The Oregon Department of Transportation is going to great lengths to cloak its $800 million I-5 Rose Quarter Freeway widening project in the language of restorative justice. Starting in the 1950s, ODOT built not just one or two, but three different highways through the historically Black Albina neighborhood, and is now back with plans to widen the largest of these, but is now pretending to care about restoring the neighborhood. To that end, its appointed an “Historic Albina Advisory Board”—after disbanding another community advisory group which had asked too many uncomfortable questions.

Housing is essential to restorative justice in Albina

The real challenge to restorative justice in Albina is more housing. The aerial photo here shows the Albina neighborhood as it existed in 1948; the red-lined areas are properties takes or demolished for the construction of Interstate Avenue in 1951, the I-5 Freeway in 1961 and the Fremont Bridge and aborted Prescott Freeway in the early 1970s. Albina was torn apart by these ODOT highway projects and its housing stock decimated. Given that ODOT’s highway building triggered the destruction of thousands of homes in Albina (the neighborhood’s population declined by more than 60 percent, from 14,000 to less than 4,000, it’s hardly surprising that getting more housing built is a key priority.

The ODOT consultants report that that one of the key strategies for building community wealth is to create affordable housing.

ODOT’s making it look like there will be housing as part of its plans

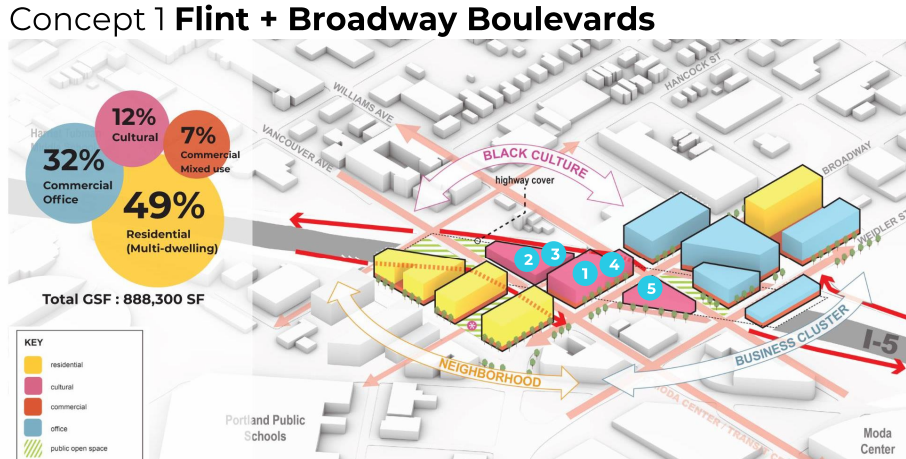

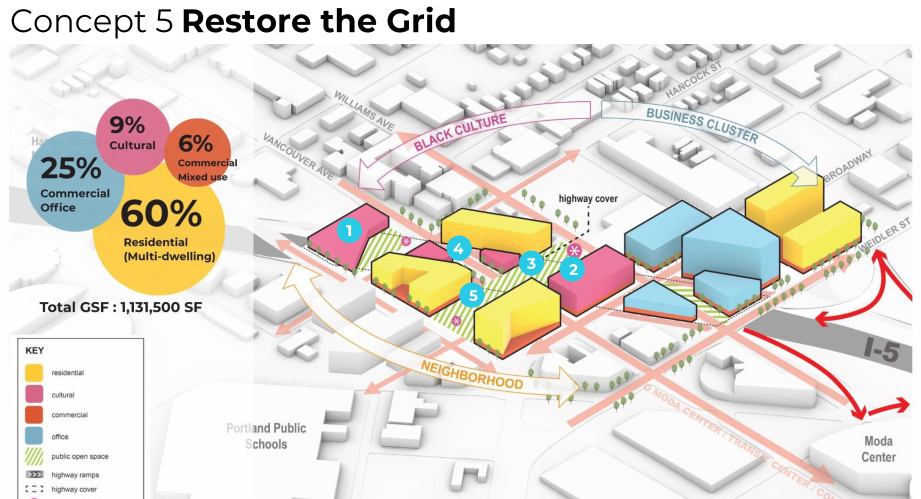

ODOT staff and consultants have presented the HAAB with surveys and focus group information on what restorative justice might look like. An “Independent Cover Assessment” consulting group has even prepared drawings showing alternative development plans for the area near I-5. The drawings feature examples from other cities of Black cultural and community facilities, and prominently include diagrams showing large new multifamily housing to be built on top of or near the freeway. Here are two such diagrams, (the yellow colored buildings are residential apartments). Concept 1 has four large residential buildings, Concept 5 has 5 large residential buildings.

But who’s going to pay for that housing? It’s going to cost $160-260 million and ODOT is offering . . nothing.

It’s all well and good to talk about housing, but how, exactly, would it get built? These colorful illustrations are really just misleading puffery and magical thinking unless there’s a realistic plan for paying for the project. The availability of the land is the easy part. The hard part is getting money for construction. To get an idea of how much it would cost, we can look just a few blocks away to the newly completed Louisa Flowers Building. It was just finished and has 204 studio, one bedroom and two bedroom apartments. Its development and construction cost about $71 million, and Home Forward, the city of Portland’s housing agency paid $3 million for the site. The project cost about $380 per square foot, with the overall cost per housing unit working out to about $350,000.

The Independent Cover Assessment shows that the residential buildings (shown in yellow) in its two concepts would make up about half to 60 percent of the 900,000 to 1.1 million square feet of buildings to be build atop or adjacent to the freeway. Those figures imply about 430,000 square feet or about 470 apartments in Scenario 1, to 680,000 square feet or roughly 740 apartments in Scenario 5.

If you could build those apartments for the same cost as Louisa Flowers (you couldn’t, of course; costs have gone up), that means the yellow colored buildings shown in these renderings would cost between $160 million and $260 million to develop and construct.

In short, unless you’ve got between $160 and $260 million (just for the housing part, mind you), those pictures are just a fantasy.

If ODOT actually had a budget for the construction of that housing, in order to, you know, promote restorative justice, then it would be perfectly valid to include this as part of the project discussion. But ODOT hasn’t committed a dime to actually paying to build this housing.

And you could say, in theory, (and it would have to be theoretical, because ODOT has made no such commitment), that ODOT would be contributing the land for these buildings. But as noted in the case of Louisa Flowers, the cost of the land is less than 5 percent of the cost of constructing the project. If housing is key to restorative justice in Albina, and if ODOT is committed to restorative justice, it seems like it ought to come up with the other 95 percent as well, rather than expecting unnamed others to do the heavy lifting for it.

Housing is essential to restorative justice in Albina. Simply drawing pictures of housing isn’t justice, it’s cynical vaporware, an attempt to create the illusion that ODOT cares, when its only real interest is in building a vastly wider freeway. The state highway department readily spent money to demolish housing in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, but apparently isn’t willing to spend any of its money to replace that housing today. And the irony is, if you really want to have restorative justice and more housing, you don’t need to build a wider freeway. In fact, a wider road would make the area less desirable for housing. ODOT’s plan to widen the freeway—and further inundate this neighborhood with more car traffic—doesn’t so much heal the repeated wounds it has inflicted on Albina, as it does to make them even worse.