City Observatory is pleased to publish this guest commentary from Miriam Pinski.

With the needed federal environmental approvals in hand, New York looks set to be the first American city to implement congestion pricing. This may be a watershed moment in transportation policy: if it can make it there, it can make it anywhere. Other cities, including Los Angeles may be ready to follow suit. Frankly, congestion pricing is long overdue, and done correctly can make a world of difference to cities.

The underlying problem with urban transportation is that we in the US underprice driving. As a result, our roads are clogged, our air polluted, and our streets dangerous.

Congestion prices can help solve those problems. A price is a signal wrapped in an incentive. Prices signal to drivers that by taking the freeway onramp at a popular hour they’re about to slow everyone else on the road down. It also gives drivers a reason to reconsider their trip–an incentive for them to wait for traffic to die down, or take a different route, or maybe shift to biking or transit.

Congestion prices make drivers pay for the time costs they impose on others. But pricing is hard, politically, and delay is just one cost that driving imposes. Is there a way to consider all the ways driving costs – and benefits – society? And to use that information to guide our transportation policy, even if we don’t have the political will to price?

There’s one city in the world that is doing just that: Copenhagen.

Copenhagen doesn’t have pricing. Even in Denmark, road pricing is unpopular. The government twice rejected it. But the city tries, as best it can, to put a value on the various positive and negative externalities from different travel modes, and to use those modes in its transportation planning.

Assigning a value to the various impacts of any travel mode is imperfect at best, controversial and wildly inaccurate at worst. Some externalities are hard to quantify. Having to put a value on a crash, or premature deaths from pollution, makes people squirm.

The city also has to quantify the impacts that a driving trip today has in the future. Time horizons matter. Calculating social costs and benefits can’t just include the immediate impacts, but the discounted future costs and benefits as well. Polluted air today might mean premature births half a year later, and lower test scores for those children a decade after that.

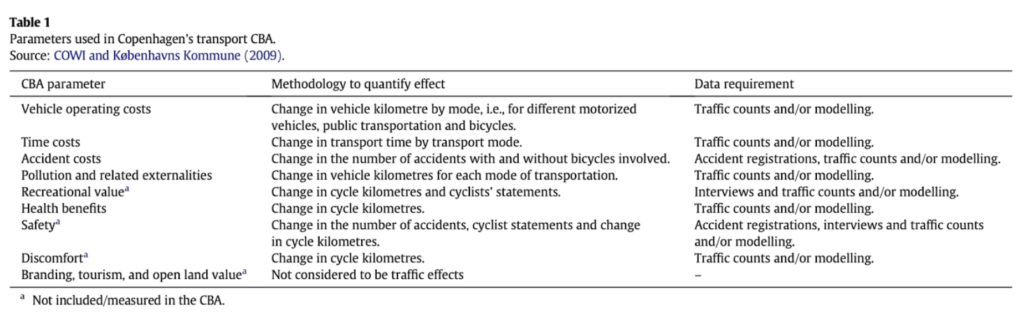

Our understanding of what those current and future impacts changes the more we learn about them. Copenhagen continually revisits its prior assumptions and revises its calculations. Fuel and energy costs fluctuate, taxes and subsidies get added and subtracted, people’s travel preferences and options change, as does our knowledge of the costs of different pollutants. The city selected a wide range of values (see the table below, from this 2015 study by Stefan Gössling and Andy S. Choi, for the indicators and how they measure them to compare driving and biking):

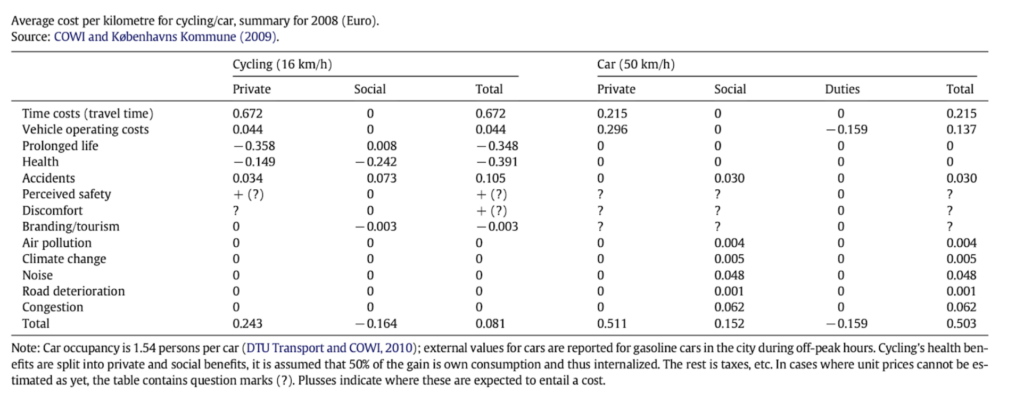

These data get turned into numbers. You can see the results below. Added up, the relative benefits of car versus bike improvements suddenly weigh much more towards the latter. What is immediately clear is how few costs individual drivers incur, and how many they impose on everyone else.

Most of the social costs of driving are canceled out by taxes. Even still, they remain expensive. Every kilometer traversed by car costs society €0.50, and every kilometer cycled benefits society €0.16. The total costs of biking are still positive (a puny €0.08), but that’s mainly because they cost cyclists time.

Copenhagen’s cost/benefit measure makes clear that driving really is quite expensive, for the individual and for society. The costs are just spread out. And while the costs of driving are only increasing over time, cycling costs seem to be declining.

The biggest personal cost of bikes is time, followed by personal and social costs of accidents. That suggests an obvious policy course: the safe and connected networks. It’s no accident that Copenhagen is one of the world’s bike capitals.

Politics are always difficult. Copenhagen did, however, establish a framework that makes it much harder to oppose projects that prioritize biking over driving. Copenhagen managed this by first forming a political consensus around the parameters, and then going forward with the analysis. Consensus comes easier when everyone first agrees on the process, and lets the outcomes flow.

Maybe this seems impossible in the US. But there are many ways to get some science back into transportation planning; pricing when it is feasible, a realistic look at costs and benefits when it isn’t. And none of this means that everyone needs to stop driving.

We don’t need to become Copenhagen to enjoy a safer, more balanced modal future. The idea that Americans require an entire cultural shift to reduce our dependence on driving leaves a lot of potential on the table. Congestion isn’t linear, and neither are its spillover effects on public health. By just taking a few drivers off the road, we can avoid complete gridlock and eliminate some of the worst externalities. It’s the last few people that enter the road that compound problems of noise, pollution and delay. The upside is that not everyone needs to stop driving for society to enjoy less trafficked streets.

While we don’t need a revolution, we can take a lesson from Copenhagen. If we stopped underestimating and hiding the social costs of car ownership, our transportation policies in the US would be less warped. The advent of congestion pricing could help us develop a useful new perspective on transportation that will lead to more just, sustainable and productive cities.

Miriam Pinski studies transportation and land use policy. Her research focuses on improving mobility among disadvantaged populations, and on making streets safer. She holds a doctorate in urban planning from UCLA, and is currently a research analyst at the Shared-Use Mobility Center. She is also writing a book about the history of the driver’s license. You can find her on Twitter @mirijulip or by email (miriam@