Part of the disparity in intergenerational economic mobility may stem from a willingness to leave home

Raj Chetty, Nate Hendren and their colleagues at the Equality of Opportunity Project have crafted a rich picture of the role that community plays in long term economic opportunity. We’ve highlighted some of their findings in the past couple of weeks. For example, proximity to jobs and nearby job creation doesn’t seem to have any positive impact on the rate of intergenerational economic mobility. It also seems to be the case that for black children, the characteristics of the neighborhood they grow up in is even more important than for white children.

The latest product of the Equality of Opportunity Project is their Opportunity Atlas, which provides a rich array of data on the characteristics and outcomes of neighborhoods throughout the nation. One feature of their new Atlas caught our eye. They include a datapoint that measures the fraction of children who grew up in a city who continue to live their as adults. For clarity, “city” in these terms means something called a “commuting zone” or CZ, which is an area defined by the federal government to include a metropolitan area and its surrounding counties. The entire nation is part of one of more than 700 commuting zones, which makes them a useful sub-state unit for characterizing economic activity. Specifically, this variable measures the percent of kids who grew up in a commuting zone who live in that same commuting zone as adults.

One of the frequently cited motivations behind economic development programs, especially in small towns and rural areas, is the hope that by creating more jobs, or the right kind of jobs, the community will be able to hold onto its kids as they grow up and move into the workforce.

The Washington Post profiled Las Animas, a town in rural Colorado that’s seen struggling economy and steady out-migration. While parents may be stuck there, their children aren’t.

Most of their kids have already left town, for good reason.

“I’m just as guilty as the next,” says Frazier, a big guy in a Green Bay t-shirt. “I encouraged them — get out of here. There’s nothing here.”

The Opportunity Atlas bears out this observation: Only about 52 percent of the kids who were raised in the Las Animas area sill live their, well below the median national rate of remaining in one’s commuting zone of 68 percent.

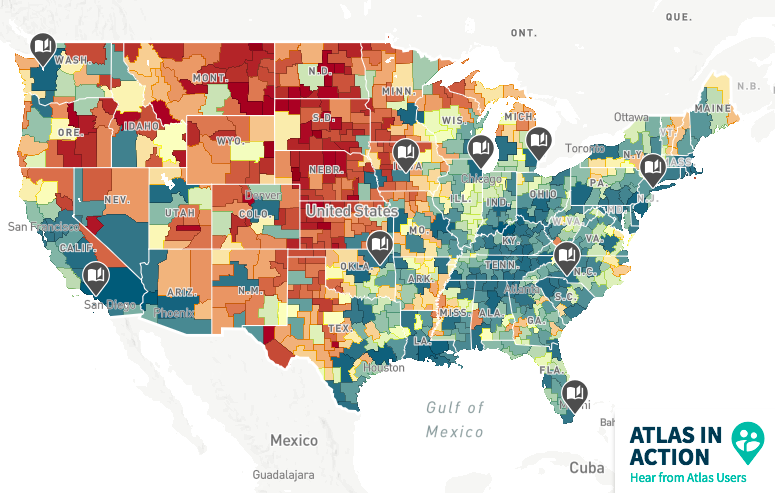

One of the interesting sidelights of the Opportunity Atlas is a rich new picture of where kids ended up living. Because they tracked children from the time they grew up until they were adults, Chetty, Hendren and colleagues have an unusually large longitudinal picture of migration trends. Their Opportunity Atlas shows what fraction of kids who grew up in an area still live their as adults. Here’s the map for the United States.

There are some very strong regional patterns. In the Great Plains and Inter-Mountain West (Iowa, Nebraska, the Dakotas, Montana, Wyoming) a relatively small fraction of kids remains in town (the dark red areas)(. In contrast, in much of the South, particularly in Appalachia and the Mississippi Delta, a high fraction of those who grew up locally still live in the same commuting zone (dark blues/greens). Some big metropolitan areas (Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, etc) also retain a high fraction of kids who grow up locally, but for different reasons than in rural areas.

There are some very strong regional patterns. In the Great Plains and Inter-Mountain West (Iowa, Nebraska, the Dakotas, Montana, Wyoming) a relatively small fraction of kids remains in town (the dark red areas)(. In contrast, in much of the South, particularly in Appalachia and the Mississippi Delta, a high fraction of those who grew up locally still live in the same commuting zone (dark blues/greens). Some big metropolitan areas (Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, etc) also retain a high fraction of kids who grow up locally, but for different reasons than in rural areas.

Contrast this map with another one that should be very familiar to those who are familiar with the Chetty/Hendren work. This map shows inter-generational economic mobility, the probably that kids who grew up in low income households achieved higher earnings as adults. There’s a strikingly similar regional contrast, with relatively high economic mobility in the Great Plains states and relatively low economic mobility in Appalachia. The following map shows children’s average income as adults, with darker blue and green colors representing relatively higher incomes and reds and oranges lower adult incomes.

This suggests to us a hypothesis: One of the chief ways that an area can contribute to the economic prospects of its children may be to prepare them to go somewhere else to pursue their dreams. One of the reasons that children growing up in rural areas in the great plains do better as adults may be that they are more likely to move away as adults. Conversely, those in much of the rural South may find it difficult to improve their life prospects because they tend not to move too far from where they grew up. At this point, our observation is just a conjecture, but with great tools like the Opportunity Atlas, its something that we can get a much better handle on.

Finally, speaking of “Get Out,” be sure to get out and vote next Tuesday, November 6. Your nation needs you.