The Oregon Department of Transportation has a decades long-tradition of ignoring Portland Public Schools when it comes to freeway projects

So here’s our story so far. The Oregon Department of Transportation, ODOT, is proposing to spend half a billion dollars widening a mile long stretch of freeway in Portland adjacent to the Rose Quarter. We’ve chronicled the numerous objections to the project at City Observatory: It won’t reduce traffic congestion, it will generate additional driving (and greenhouse gas emissions), it will lower the quality of life in the central city, doesn’t do anything to address the carnage of ODOT roadways, and a host of other concerns.

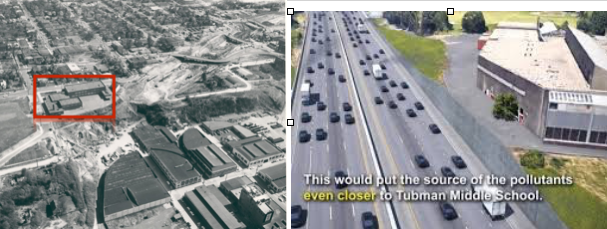

A key problem with the project is that it expands the footprint of the I-5 freeway into the school grounds of the Harriet Tubman Middle School. As we’ve related at City Observatory, the school (which predates the freeway by a decade) bears the brunt of air pollution, which has increasingly been shown to affect student achievement. (It’s also monumentally unfair that cash-strapped Portland Public Schools have had to spend millions to filter the school’s air enough to make it breathable for students). Suffice to say, Portland Public Schools has raised serious concerns about the project.

Like thousands of other Portlanders, the school board has asked ODOT to prepare a full-scale environmental impact statement, one which would fully disclose the project’s health and environmental impacts and fully consider alternatives. For a time, it appeared that ODOT would acquiesce to these demands.

But now, it appears that ODOT plans to plow ahead based solely on its flawed, short-form Environmental Assessment, ignoring the school board’s concerns. As Blair Stenvick of the Portland Mercury reports, PPS officials are angry. They’ve adopted a resolution calling out the Oregon Transportation Commission for moving forward without a careful look at the serious issues that have been raised:

“At this time,” reads the PPS resolution, “the OTC has privately stated that it plans to unilaterally take action at its December 17 public meeting without addressing any of the troubling and significant impacts that the widening will have on students and community health.”

To anyone familiar with the history of the I-5 freeway, this shouldn’t come as any surprise. This is exactly what the Oregon State Highway Department (what ODOT used to be called), did to Portland Public Schools 60 years ago when this segment of the I-5 freeway was first built. Back when it was just a line on the map, it was called the “Minnesota” freeway, because its proposed route essentially obliterated Minnesota Avenue. The I-5 route sliced trough the schoolyard of the Eliot School (shown above in red), bisected the attendance areas of several other schools, closed off dozens of city streets, and focused traffic on others that were prime travel routes to local schools. Not surprisingly, local school district officials were alarmed. But the planning process gave them little opportunity to voice their concerns.

Let’s turn the microphone over to Eliot Henry Fackler, writing his master’s thesis “Protesting Portland’s Freeways: Highway Engineering and Citizen Activism in the Interstate Era” at the University of Oregon about the freeway fight (published in 2009). Just as today, in the early 1960s, PPS officials raised serious concerns about the freeway’s impacts on students. It was assured that their concerns would be addressed, but . . . the agency went ahead with its plans exactly as announced, making no allowances for the school district’s concerns.

It did not take long for Portlanders to see the negative consequences of imposing massive interstate highways on a functional cityscape. On June 23, 1961, the Portland City Council and state road engineer Tom Edwards met with citizens concerned over permanent street closures caused by the partly-finished Minnesota Freeway. The route, a section of Interstate 5, sliced through the city’s Albina neighborhood.

Fifty-one streets had already been dead-ended to make way for the new depressed highway in the city’s only predominantly African American neighborhood. “I think it is unfortunate that this has not come to our attention until at this late time,” Howard Cherry, a member of the Portland School Board stated. “I would like to be heard at a proper time with the council and the highway commission.” Likewise, Daniel McGoodwin of the American Institute of Architects (AlA) implored the Highway Commission to “find a less damaging solution.” Reading from a statement prepared by the AlA, McGoodwin argued that the freeway “would create a great problem for the city and disrupt long established neighborhood patterns.”

The criticisms made by a qualified architect like McGoodwin put City Commissioner William Bowes on the defensive. “We have done everything you can think of to make it as attractive as possible,” he said, adding, “if you can call a freeway attractive.” The most incisive critique came from local architect Howard Glazer who complained that the highway designers’ failure to consult with residents was “an example of what’s happened before and will undoubtedly happen again.” When presented with a map showing the freeway skirting the edge of the neighborhood, Glazer pointed out that the map “is a slice of the city and doesn’t show adjacent territory.” No matter how carefully they were planned, urban interstates would reduce residents’ ability to quickly get groceries, visit friends, go to school, or attend church. At the meeting’s conclusion, state engineer Edwards assured those in attendance that “every attempt will be made to solve these problems.’, The freeway opened to traffic in December 1963. No changes were made to the route.

The portents were today’s experience were clearly foreshadowed in the original debate over the freeway. Some of the most important–and to today’s ears, familiar, arguments were featured in a June 24, 1961 story published in the Portland Oregonian (from which Fackler’s story is, in part, drawn).

It’s clear that the highway department was simply announcing what it was going to do, with no real thought given to modifying its plans. Attorneys confirmed that the process was not to consider objections, the Portland school board had been given no notice, and was assured it would be listened to–and was then ignored. Even at the time, participants foresaw that this would happen again.

The City Attorney advised the public attending the City Council meeting that it was simply an information session, not a hearing, and that they had nothing to say about the freeway; the Oregonian relates:

City Attorney Alexander Brown said, “This is not a hearing, it’s an informational meeting. It is unfortunate that the word ‘hearing’ was used in connection with this session. The inference of a hearing is that objections may be considered.”

Dr. Howard Cherry, a member of the Portland School Board objected to the freeway’s poor planning, saying:

“I think it is unfortunate that this has not come to our attention until at this late time. And I would like to be heard at a proper time with the council and the highway commission.”

According to the reporting by the Oregonian, City Commissioner William Boles

“assured Cherry that the council will be very glad to sit down and discuss the problem of traffic on Alberta Street with the school board.”

Presciently, one prominent citizen who testified, Howard Glazer, worried about the effects of the freeway on local street traffic and warned that the state had regularly–and would again, ignore local concerns:

“. . . an example of of what has happened before, and will undoubtedly happen again.”

As today’s Portland school board members, it is happening again. For history buffs, here’s a grainy image of the June 24, 1961 Portland Oregonian story. Deja vu!

Editor’s Note: This commentary has been revised to note that the Portland School Board has adopted the resolution calling for a full environmental impact statement.