To ballparks, convention centers and starchitect museums, add urban aquariums.

To some boosters, your city is only one world-class visitor attraction away from economic prosperity. That pitch has been used to sell and endless series of public subsidies for baseball parks, football stadiums, basketball and hockey arenas, convention centers (and their appurtenant “headquarters hotels”) and starchitect-designed museum buildings. To that long list, we might add aquariums.

To be sure, there are many breath-taking and well-patronized aquariums around the country. They include established institutions like the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago, San Francisco’s Steinhart Aquarium and New York City’s Municipal Aquarium. There are splendid new aquariums like the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California, and Atlanta’s Georgia Aquarium.

There have been many new aquariums opened in the US over the last two decades with the hopes of attracting visitors and stimulating city economies. According to the Association of Zoos and Aquariums there are 52 certified aquariums in the US (and another 8 aquariums that are part of larger zoos). And even more may be in the offing. One of the latest proposals has surfaced in Detroit. Boosters in the Motor City have resurrected long dormant plans to build a large aquarium in downtown. It’s worth asking: Would an aquarium be a municipal asset and visitor attraction for your city?

Financial risks abound in the aquarium business

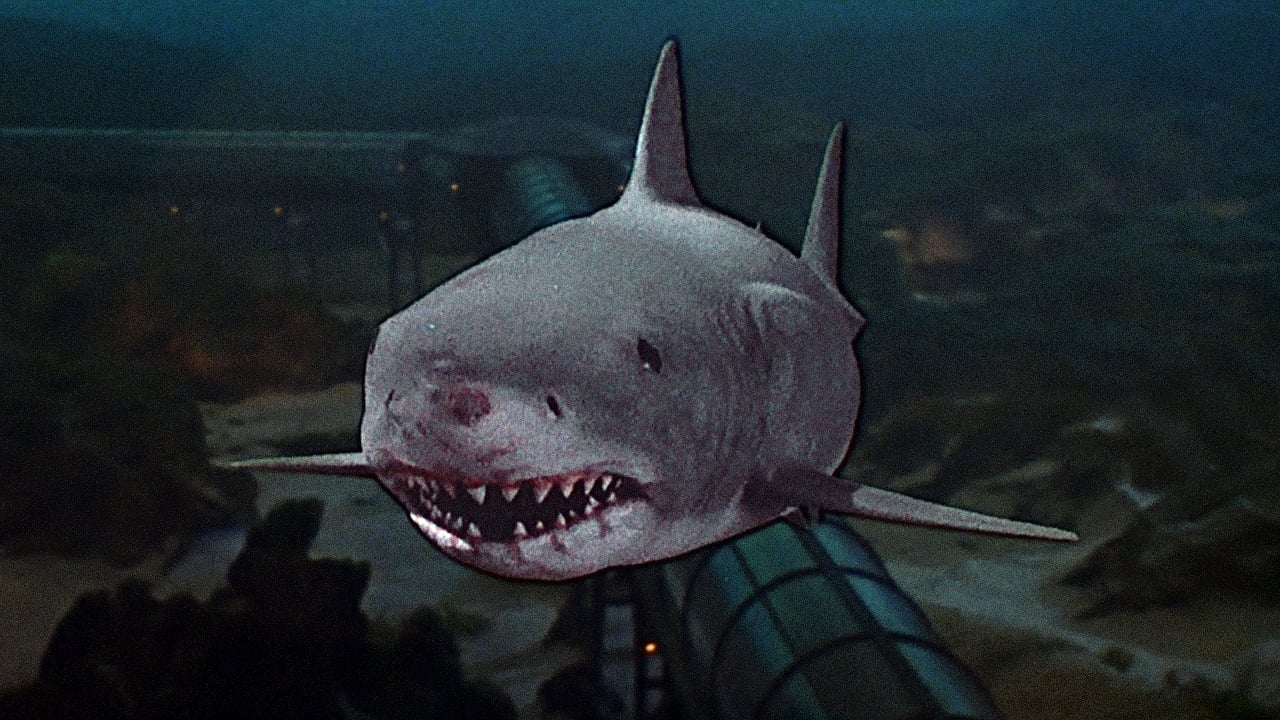

As our grinning friend from the thoroughly forgettable third installment of the Jaws franchise reminds us, there are remorseless financial aspects to the aquarium business. For those who’ve been spared the pleasure, Jaws 3 is set in a Sea World aquarium in Florida that decides to try to exhibit a captured baby great white shark in its park; its mother–pictured above–has other ideas about her offspring’s housing arrangements.

The fact that they can work spectacularly well in some instances, doesn’t necessarily mean that every one will be a financial success or a material contributor to community economic development (which is not to gainsay the educational or amenity benefits of having such an institution in one’s community.)

There’s a classic joke about investing that seems like it should apply to financing aquariums: “The best way to make a small fortune in aquariums is to start with a large one.” There are a handful of big aquariums that have been financially steady, but these tend to have very generous charitable givers. Construction of the Monterey Bay Aquarium was underwritten substantially by donations from the Packard family (of Hewlett-Packard fame). Home Depot’s founder gave $250 million to build the Georgia Aquarium, for example. Big equity contributions up-front mitigated the need to go into debt to create the facility.

Not everyone has such deep-pocketed donors to underwrite the cost of aquariums. It’s more common that local municipalities are asked to make a substantial up-front contribution to the cost of building a facility, and not unusual that cities end up shouldering ongoing operating costs as well as being the ultimate guarantor of debt. There’s a litany of communities that have started, supported, or subsidized local aquariums who have had very mixed financial results.

- Tampa: City ended getting up stuck repaying $84 million in debt issued for its aquarium. It will be paying $7 million a year on the bonds, plus a half million in operating subsidy to the aquarium, plus it pays insurance bills for the facility of about $150,000 annually.

- When Denver’s aquarium folded it stuck private debtors with $57 million in bad debt. The facility was built at a cost of $93 million in 1999, but folded in 2005 and was sold in bankruptcy for $13 million. It’s now owned and operated by the Landry Restaurant group.

- Long Beach’s Aquarium of the Pacific has been heavily subsidized by the port and city of Long Beach (which uses revenue it gets from oil leases to pay subsidies).

- Citibank had to write off $15 million in lent for the construction of an aquarium in Mystic, Connecticut when attendance failed to meet projections.

- Gulfport, Mississippi is building a $93 million aquarium set to open in 2019; the City has issued $35 million in debt (for which it will be liable); the facility also got a $17 million federal grant (out of oil spill compensation funds).

- Tulsa build an aquarium which got a $12 million grant from the city out of “Vision 2025” sales tax package, but since that has expired, the city is now responsible for ongoing debt.

- Shreveport has a privately run aquarium in a city building that has had problems paying its bills.

Even the most successful aquariums have to cope with the “honeymoon” effect. Aquariums tend to do well when they open, but the blossom can quickly fade. Atlanta’s Georgia Aquarium attracted 3.5 million visitors in the first year it was open, but attendance quickly fell to fewer than 2 million visitors per year, once the novelty had worn off. An article on the aquarium’s marketing efforts in the Harvard Business Review concluded that this is a regular occurance with aquariums. That then prompts efforts to invest in new exhibits and attractions that will give patrons a reason to come again. In the case of some aquariums, like Long Beach’s Aquarium of the Pacific, that means they are taking on additional debt for expansion at the same time they’re relying on increasing public subsidies to pay off old debt.

Investment Advice?

For cities looking at proposals to build aquariums, it would be great if there were some off-the-shelf, or industry-standard metrics for gauging the prospects and risks of the next city aquarium. Is this a growth industry? Is the market saturated? What does it take to compete? What are realistic assumptions about capital costs, and what does it take to have a facility that can keep the doors open without ongoing subsidies?

The industry is represented by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums which publishes some general information about the number, location and overall visitor counts of zoos and aquariums. There are also occasional prospective economic impact reports on the potential benefits of building aquaria–but they generally fall into the category we’ve called “hagiometry“–paid flattery with numbers. What seems to be lacking is the kind of careful comprehensive assessment of risks and a critical independent analysis of attendance projections and financial estimates, the kind of analysis that the University of Texas at San Antonio’s Heywood Sanders authored for the Brookings Institution on the economics of convention centers. In the absence of such information, we can only invoke the old advice: Caveat emptor.