What’s equitable about spending six times as much per homeless person in the suburbs as in the city?

The “equity” standard that’s guiding the division of revenue for Metro’s housing initiative is based on politics, not need.

Portland’s regional government Metro is rapidly moving ahead with a proposed $250 million per year program to fight homelessness.

It’s plainly motivated by the fact that the growth of homelessness in Portland is a highly rated public concern-a third of Portland residents identified it as a #1 concern, up from just 1 percent nine years ago. Public concern with homelessness is such that Metro fears it will have trouble getting widespread support for its $4 billion transportation initiative if something isn’t done to address homelessness.

So after saying the homeless measure could wait until after the Transportation measure is put to the voters (in November), the Metro Council is moving on a hurried schedule to craft a homeless measure to appear on the region’s May 2020 primary election.

It’s plainly a rush job: the proposed ordinance creating the program was first made public on February 4, had its first public hearings on February 14, and would need to be adopted by the Council by February 27 in order to qualify for the May ballot. The measure is very bare bones, it provides only the loosest of definitions about who is eligible to receive assistance and what money can be spent on.

The thing it is clear about, however, is how the money will be allocated, Each of Portland’s three counties (Clackamas, Multnomah and Washington) will split 95 percent of the funds raised region-wide in proportion to their counties share of the Metro district’s population. And counties will be in the driver’s seat for deciding how funds are spent in their counties. Aside from 5 percent reserved for regional use (including administration), Metro is acting solely as the banker for homeless services.

SECTION 7. Allocation of Revenue Metro will annually allocate at least 95 percent of the allocable Supportive Housing Services Revenue within each county based on each county’s Metro boundary population percentage relative to the other counties.

DRAFT EXHIBIT A TO RESOLUTION NO. 20-5083

WS 2-18-2020

Concern about homelessness is, perforce, an equity issue. Those who are living on the street or in shelters are plainly the among the worst off among us, and dedicating additional public resources to alleviate their suffering and provide them shelter seems like an intrinsically equitable endeavor.

Metro’s proposed adopting resolution is outspoken about clothing the entire effort as the alleviation of vast and historic wrongs: It finds:

WHEREAS, communities of color have been directly impacted by a long list of systemic inequities and discriminatory policies that have caused higher rates of housing instability and homelessness among people of color and they are disproportionately represented in the housing affordability and homelessness crisis

(Draft Resolution No. 20-5083 WS 2/18/20)

That principle is followed up in Metro’s proposed enacting ordinance which would requireeach of the counties receiving funds adhere closely to Metro’s own statements about what constitutes equitable planning processes. Specifically, Metro mandates that counties allocate funds in a way that redresses inequities.

A local implementation plan must include the following:

…..

2. A description of how the key objectives of Metro’s Strategic Plan to Advance Racial Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion have been incorporated. This should include a thorough racial equity analysis and strategy that includes: (1) an analysis of the racial disparities among people experiencing homelessness and the priority service population; (2) disparities in access and outcomes in current services for people experiencing homelessness and the priority service population; (3) clearly defined service strategies and resource allocations intended to remedy existing disparities and ensure equitable access to funds; and (4) an articulation of how perspectives of communities of color and culturally specific groups were considered and incorporated.DRAFT EXHIBIT A TO RESOLUTION NO. 20-5083 WS 2-18-2020

Counties have to “remedy existing disparities and ensure equitable access to funds,” within their counties. That policy doesn’t apply, however, with Metro’s allocation of funds within the metropolitan area. That’s because 95 percent of the funds raised by Metro (after deducting its administrative costs) are to be allocated to counties based solely on population. But by every imaginable definition of homelessness, the homeless are not evenly distributed proportional to the overall population. Homelessness in all of its forms, and particularly in its most serious forms–the unsheltered living on the streets and the chronically homeless, who’ve been without a home for a year or more–are dramatically more concentrated in Multnomah County than in the two suburban counties (Clackamas and Washington). In addition, three-fourths of African American homeless and seven of eight Latino homeless persons in the region live in Multnomah County. The county with the largest burden of dealing with homeless persons of color gets far less resources, per homeless person, than surrounding suburbs.

Where the homeless live in Metro Portland?

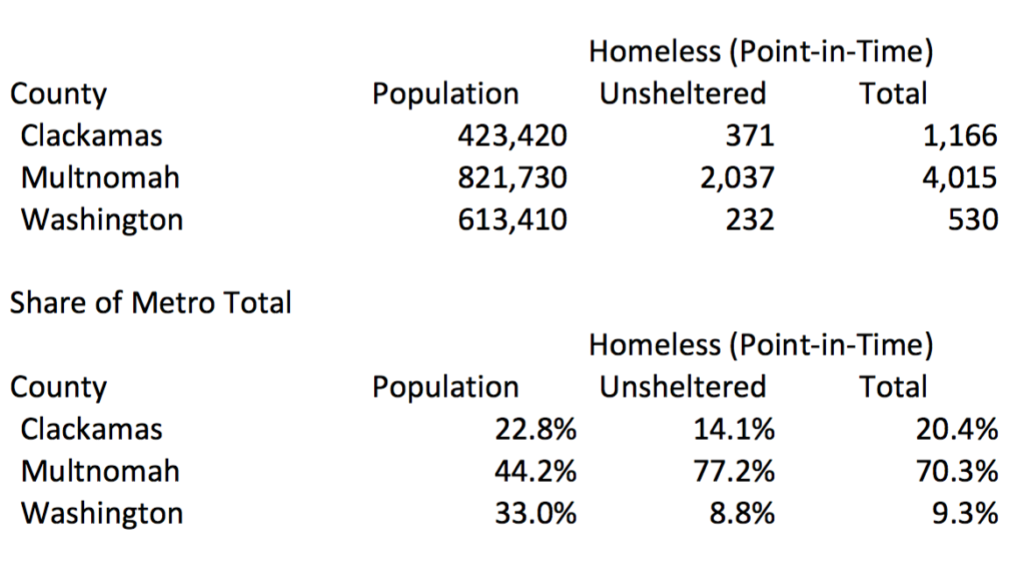

Here we explore the data gathered in the 2019 “Point-in-Time” surveys of the homeless population in Clackamas, Multnomah and Washington Counties. The Point-in-Time data collection effort probably understates the magnitude of the homelessness problem, but provides the best data on its location within the region, and the clearest picture of the race and ethnicity of the homeless.

We focus on two data points from the Point-in-Time Survey : the unsheltered population (people living in the streets) and the total homeless population, which includes sheltered homeless (in shelters, missions, or temporary accomodation). The following table shows the latest data on the populations of the three counties, and the number of persons counted as homeless in the latest (2019) Point-in-Time survey. The first panel of the table shows the actual counts; the second panel shows the percentage distribution by county. Multnomah County constitutes 44 percent of the region’s population, but is home to about 77 percent of the region’s unsheltered homeless and about 70 percent of the region’s total homeless population. Unsurprisingly, homelessness in Portland, as in most of the United States is concentrated in urban centers.

Multnomah County constitutes 44 percent of the region’s population, but is home to about 77 percent of the region’s unsheltered homeless and about 70 percent of the region’s total homeless population. Unsurprisingly, homelessness in Portland, as in most of the United States is concentrated in urban centers.

Notice that the Metro ordinance provides that funds will be allocated not according to the homeless population in each county, but the total population in each county. What this means in practice is that some counties will get much more than others relative to the size of their homeless population (and by implication, homeless problems). Multnomah County also has a higher proportion of homeless people who are “unsheltered” than Clackamas or Washington Counties. Multnomah County also accounts for three-quarters of those in the three counties who are classified as “chronically homeless.”

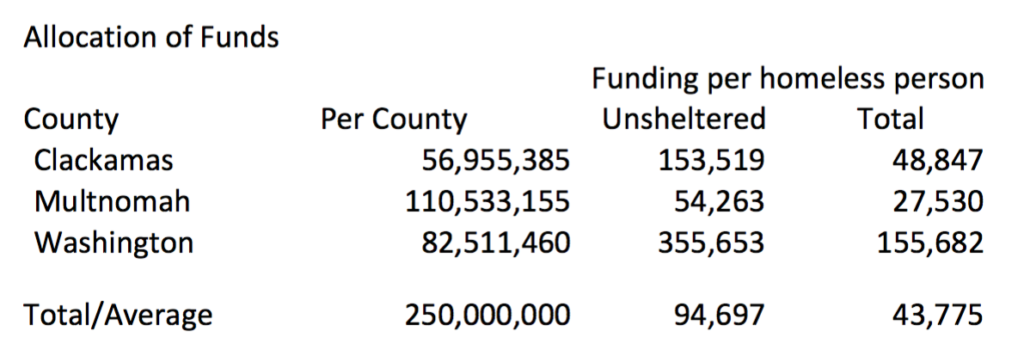

We’ve computed the estimated allocation of a $250 million per year program based on overall county population, as shown the the following table. Each county gets the same share of the $250 million total as its share of total population: Multnomah County gets 44 percent or about $110 million, and the other counties get proportionate amounts. We’ve also computed the amount that each county gets per homeless person and per unsheltered person. We use the relative size of the unsheltered and homeless population in each county to index the need, and show how much is available in each county relative to that need.

These data show that on a per homeless person basis, Washington County gets about five to six times as much as Multnomah County, and that Clackamas County gets about two to three times as much as Multnomah County. Per unsheltered homeless person, Multnomah County gets $54,000; while Washington County gets more than six times as much: $355,000.

To be clear: This table is using a “per homeless person” measure not as an absolute indicator of spending per person. The scope of the homeless problem overall is larger than captured by the point-in-time survey, and also the measure is intended to be broader, i.e. providing rent subsidies to keep households from becoming homeless. But we take this figure as a robust indicator of the relative need in each county, and the resources that each county has relative to the need, as identified by the most severe and acute aspect of the homelessness problem.

(Note that using county totals doesn’t correspond exactly to the provisions of the Metro ordinance. Only the population within the Metro boundary (which excludes outlying cities in each county) constitutes the basis for the distribution. Excluding these areas would affect both our estimates of the allocation of funds and our estimates of the homeless population in each county. For this analysis, we have relied on published and available county totals.)

This system of allocation works to the disadvantage of persons of color. Multnomah County accounts for more than three-quarters of the homeless persons in the region who are Black or Latino. According to the three county’s Point-in-Time surveys for 2019, Multnomah County accounted for 373 of the region’s 582 Black homeless (76 percent) and 648 of the region’s 743 Latino homeless (88 percent). What Metro’s measure does is to replicate, if not amplify, the racial and ethnic inequity of the homeless in Multnomah County by providing them vastly smaller resources than it provides per homeless person in the suburban counties.

If this effort is all about political coalition building, and if each county is viewed as a separate fiefdom, then slicing the revenue pie proportional to population makes sense. But if homelessness is really a shared regional concern, and if Metro is really a regional government–rather than just a revenue-raising and pie-slicing middleman for counties, then it really ought to embrace the logic of its own rhetoric about equity, and about impact.

If three-quarters of the homeless are in Multnomah County, then Metro ought to spend most of the region’s resources there. There’s no plausible regional argument for spending five or six times as much on a homeless person in Washington County than on an otherwise similar homeless person in Multnomah County. If Metro is serious about overcoming decades of discrimination against communities of color who’ve been disadvantaged in their access to resources then it should devote at least as much, per homeless person to those communities as to others.

Funding in search of policy and results

Everyone recognizes that homelessness is a complex, gnarly problem. But aside from sketching the outer boundaries of what’s permissible, and asking counties to report what they spent the money on, there’s nothing in this measure that spells out a strategy, or expected results, or really established any real accountability. The “outcome-based” portion of the ordinance actually says nothing about outcomes. It basically just says “counties, do what you think best.”

SECTION 11. Outcome-Based Implementation Policy

Metro recognizes that each county may approach program implementation differently depending

on the unique needs of its residents and communities. Therefore, it is the policy of the Metro Council that there be sufficient flexibility in implementation to best serve the needs of residents, communities, and those receiving Supportive Housing Services from program funding.

What this tells us about equity

It’s become increasingly fashionable to talk about the equity implications of public policy. For many governments, and Metro in particular that takes the form of long lamentations about past injustices and ornately wordy but nebulous commitments to assure engagement and participation and to hear the voices of the those who’ve been disadvantaged by past policies. But the clearest way to judge the equity of any proposal is to look past the rhetoric and look to see where the money is going. And in the cases of this measure, which is pitched at dealing with a problem that disproportionately affects the region’s central county, it ends up devoting a disproportionate share of resources to suburban counties.

Equity has to be more about allocating resources to areas of need and insisting on measurable results, rather than just performative virtue signaling and ritual incantations of historic grievances. When you look at the numbers associated with this measure, you see that real equity considerations take a back seat to the lofty rhetoric.

If you’re homeless in the Portland area, it shouldn’t matter what county you live in. But Metro’s proposed allocation system would provide vastly fewer resources per homeless person in Multnomah County. That’s particularly ironic in light of the fact that most of the persons of color who are homeless in the region live in Multnomah County. If you’re looking to redress the resource inequities that have worked to the disadvantage of these groups, this approach doesn’t do that.

Editor’s Note: As of this writing, its unclear how much money the voters will be asked to provide. As Oregon Public Broadcasting reported:

Metro was hoping to raise $250 million to $300 million per year, but it appears the tax it proposed might raise only about half that amount. Latest estimates are it would provide $135,000,000 per year.

This post has been revised to correct formatting errors.