A key design element of the supposedly pedestrian friendly Rose Quarter freeway cover is a pedestrian hostile diverging diamond interchange

One of the main selling points of the plan to spend nearly half a billion dollars widening the Interstate freeway near downtown Portland is the claim that the improvements will somehow make this area safer for pedestrians. Much of the attention has been devoted to a plan to partially cover the freeway and state and city officials say the covers would provide more space for bike lanes and wider sidewalks. While that sounds promising, in practice the covers are really just a slightly wider set of highway overpasses chiefly dedicated to moving cars, and with badly fragmented and un-usable public spaces. The covers/widened overpasses are part of a re-design of the on-ramps and approaches to Interstate 5, including a re-working of the local street system.

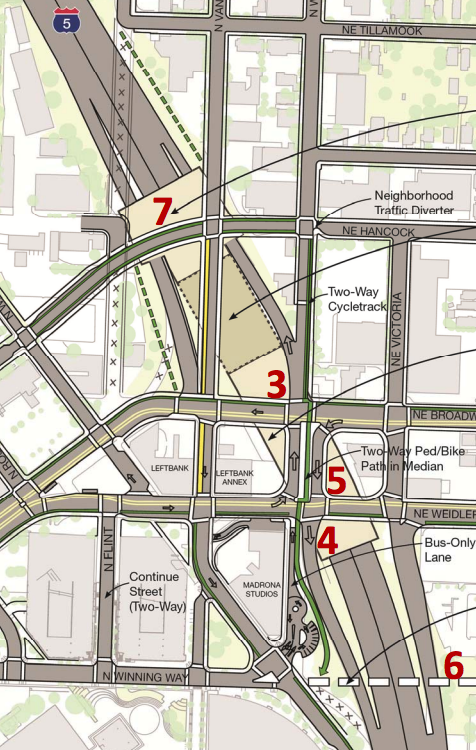

The centerpiece of that redesign is a miniature version of a diverging diamond interchange. Currently, two one-way couplets, one going East-West (N.E. Broadway and N.E. Weidler) and the other going North-South (Vancouver Avenue and Williams Avenue) intersect atop the freeway, and also lead directly to freeway on-ramps and off-ramps. This arrangement produces a high number of left turn movements at this pair of intersecting streets. In an effort to reduce turning movements and speed the flow of auto traffic, the engineers are proposing a double diamond arrangement, which converts a block long portion of N. Williams Avenue into a two-way street, with traffic running on the left-hand side of the the road (i.e. the opposite of the usual American pattern). This reverse-flow two-way street is the central feature of the larger of the two “covers” over the freeway, further emphasizing that these are hardly recreational green space but are an auto-dominated zone.

Here’s an overview of the project.

And here’s a detailed view of the diverging diamond feature. The two reverse direction lanes are separated by an island which contains a two-way bike and pedestrian path (shown in green). The purpose of the diverging diamond is to straighten the approach routes to the freeway’s on-ramps and speed automobile traffic. Notice that the radius of curvature of the corners from eastbound NE Weidler onto the northbound couplet and from westbound NE Broadway onto the southbound couplet have been increased to allow higher speed turns than normal city blocks.

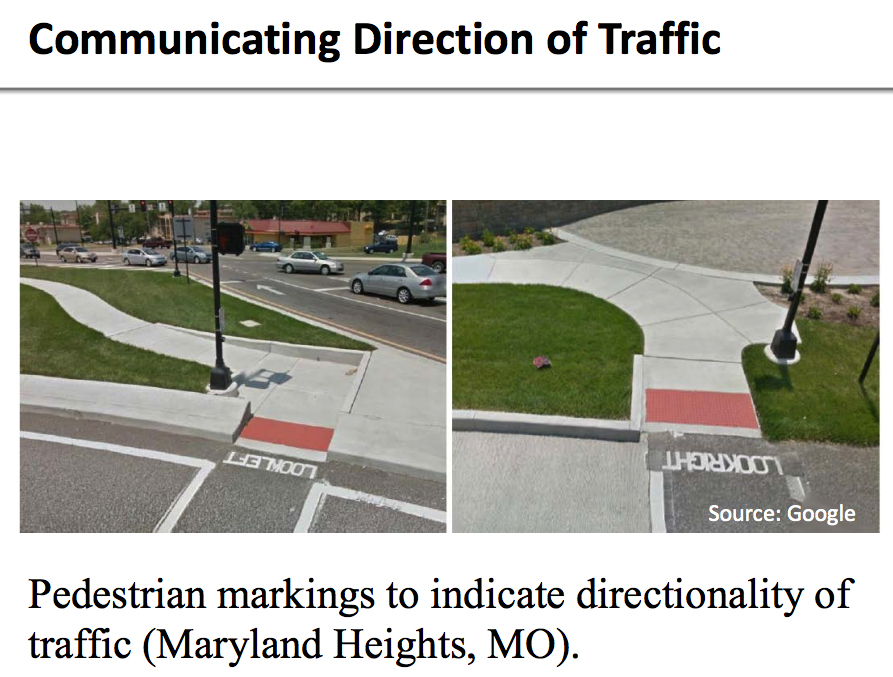

This arrangement is hostile to pedestrian and bike movements for a number of reasons. For east-west traffic, the number of crossings is increased: pedestrians have to cross from one side of the couplet, first to the center island, and then across the other side of the couplet. For both of these crossings, traffic is moving in the opposite direction of every other two-way street in the city. In other diverging diamond installations, engineers have put down pavement markings to warn pedestrians that traffic is coming from an unexpected direction. (These and several following illustrations are drawn from a North Carolina State University study of diverging diamond interchanges published by the Transportation Research Board.)

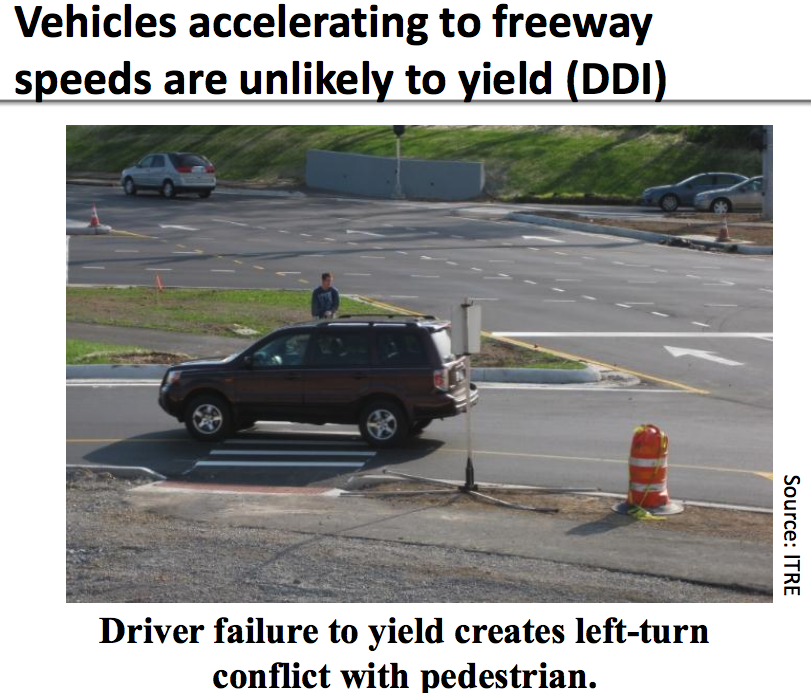

For pedestrians and bikes going north/south on Williams, they’ll be channeled onto a narrow island between two opposing lanes of traffic, with both lanes serving as accelerating lanes for vehicles entering the freeway northbound and southbound. The southbound portion of the couplet consists entirely of vehicles getting on the freeway. The higher speeds at turns and on these “on-ramp” streets are particularly dangerous to pedestrians. That’s an identified problem with the diverging diamond approach.

As they’re getting ready to accelerate to freeway speeds, drivers may not be looking for pedestrians. Schroeder’s study of diverging diamonds reports that vehicles accelerating to freeway speeds are unlikely to yield:

Our colleague Chuck Marohn at Strong Towns took a close look at arguments that the diverging diamond creates a pedestrian friendly setting. In his view, that’s a claim that would only fool a highway engineer. He’s got a video walk-through of a diverging diamond in Missouri that shows how hostile these intersections are to foot-traffic. His conclusion: the diverging diamond is an “apostasy when it comes to pedestrians and pedestrian traffic.”

Despite claims that the Rose Quarter freeway widening project is designed to improve pedestrian access and knit together this neighborhood’s fragmented street grid, pretty much the opposite is happening here. Introducing a diverging diamond into the landscape is plainly designed to move more cars faster. It creates a more difficult and disorienting crossing for pedestrians and hems in the area’s principal North-South bike route between two reverse-direction roadways that are essentially freeway on-ramps. Its wider turns and straighter freeway approaches encourage cars to go faster, and make drivers less likely to yield to pedestrians. If Portland is really interested in making this area more hospitable to pedestrians, this almost certainly isn’t the way to do it.

Reference:

Bastian Schroeder, Ph.D., P.E. Director of Highway Systems, NC State University, Institute for Transportation Research and Education, Observations of Pedestrian Behavior and Facilities at Diverging Diamond Interchanges. (2015)