The greatest urban myth of the Covid-19 pandemic is that fear of density has triggered an exodus from cities.

US Post Office data show that the supposed urban exodus was just a trickle, and Americans moved even less in the last quarter than they did a year ago.

At City Observatory, we’ve regularly challenged two widely repeated myths about the Coronavirus. The first is that urban density is a cause of Covid-19, and the second, and closely related, is a claim that fear of density in a pandemic era is sending people streaming to the suburbs and beyond.

Are we moving more?

If there were any truth to the urban exodus stories, you’d expect it to clearly show up in increased migration. But are more people moving now that pre-Covid-19? One of the clearest ways to get a handle on this is through the US Postal Service. When people move from one home to another, they fill out a change-of-address form. The USPS tabulates this data monthly, and helpfully distinguishes between temporary and permanent moves.

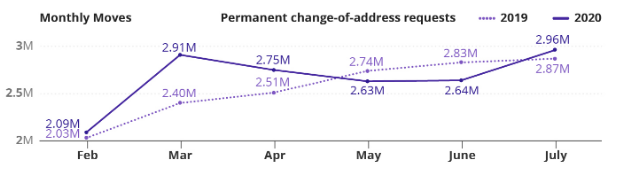

MyMove.Com, a moving services website has prepared a new report summarizing these data. The most compelling chart shows monthly data on permanent changes of address for 2019 and 2020.

If we believe the “urban exodus” theory, we’d expect to see a large and sustained increase in changes-of-address in the months after the advent of the virus, compared to the same month in the previous year. The data show nothing of the kind. While there’s a jump upward in moves in the first months of the virus—total moves up by about 21 percent compared to the year earlier in March and 10 percent in April, that surge didn’t persist.. (The month to month variation in 2019 and 2020 is pretty similar, suggesting that the variation in movement is normal, rather than unusual). Moreover, though, total changes-of-address declined in May and June compared to the same months in 2019—precisely the opposite of what one would expect if the Coronavirus had prompted people to migrate. Perhaps the most charitable explanation one can attach to the data is that the pandemic accelerated some moves–moves that would have happened in the summer, happened earlier; that would explain the jump up in March and April and the subsequent slide in May and June.

In the last three months for which there is data—that is, combining data for May, June and July—changes of address are down 2.5 percent compared to 2019. Bottom line: If the pandemic permanently changed expectations, we should be seeing a steady increase in moving, compared to a year ago: we don’t. The “more moving” myth is busted.

Spinning the moving data

The lack of any increase in permanent moves should completely puncture the “urban exodus” claims, but that’s such a durable meme that those who write about the data can’t seem to bring themselves to concede it’s wrong. In releasing its report, MyMove breathlessly plays up the urban flight story. It’s release is titled, “Coronavirus Moving Study: People Left Big Cities, Temporary Moves Spiked In First 6 Months of COVID-19 Pandemic.” The body of the release claims (with no data) that:

Now that people can continue with their life remotely, they can do so from anywhere. And so people are leaving big, densely populated areas and spreading out to suburbs or smaller communities across the country — at least for now.

The report’s subhead shouts out the plays up the statistic that:

Over 15.9 million people have moved during the coronavirus, according to USPS data.

But lots of Americans are always moving. You have to dig a bit deeper to see that 15.4 million people moved in the same months of the preceding year, which means that there’s been only about a 4 percent increase in total moves. In addition, most of that increase is due to temporary moves, not permanent ones; permanent moves are up just 2 percent.

Once again we have a report that implies that there’s an urban exodus, but then presents data that shows there’s been virtually no change in the level or pattern of moves compared to pre-Covid days.

The MyMove report also repeats the false claim about a connection between urban density and Covid:

The impact of urban density on coronavirus moving trends:

. . . it’s only logical that large, densely populated cities and crowded spaces present a higher risk of spreading and contracting COVID-19, and that people would relocate to areas with fewer people, where the risk of infection could be lower.

True, denser cities were hit first, but we and others have presented detailed statistical evidence discrediting the “density=covid” claim. Moreover, in the past two months, the character of the pandemic has completely reversed: Covid-19 is now a rural and red state plague. New cases are far more prevalent in rural American and small metro areas, while the nation’s densest urban counties now have the lowest number of new cases per capita.

The anti-urban bias that conceals the continued strength of cities

While the copywriters haven’t seemed to have figured this out yet, the underlying data shows that there hasn’t been a surge in permanent migration, and the cities aren’t hemorrhaging residents. The data, unlike the copy, puncture the myth of an urban exodus.

Our recent report, Youth Movement, confirmed the depth and breadth of the long-term trend of well-educated adults moving in large numbers to close-in urban neighborhoods. And the real-time data from real estate market search activity confirmed that cities were still highly attractive, gaining market share in total search activity from suburbs and more rural areas, according to data gathered in April by Zillow and Apartment List.com

As we pointed out this summer, real-time data on apartment search activity showed that interest in cities increased, rather than decreasing. Data compiled by Apartment List.com economists Rob Warnock and Chris Salviati for nation’s 50 largest metro areas between the first and second quarters of 2020 showed interest in cities actually increased in the second quarter compared to the first, relative to other locations, including suburbs, other less dense cities, and rural areas. The findings are the exact opposite of what one would expect if the headlines about an urban exodus were correct. Rather than looking to less dense suburbs, or exploring other states, apartment search activity is focusing more on dense city locations.

In a fact-based world, that would put an end to these “fleeing the cities” stories. What the claims of urban exodus reflect are a persistent anti-urban bias embedded in many of these accounts. The “teeming tenements” view of cities underlies many of the misleading anecdote fueled stories about people leaving cities. Sadly, the idea-virus that is the urban exodus myth seems just as persistent as the Coronavirus itself. But at City Observatory, we’ll keep working on the vaccine.