Are home prices appreciating more or less in black neighborhoods? Is that a good thing?

Today, in part 2 of our analysis of the home price gap between majority black and predominantly white neighborhoods we look at the pattern of home price appreciation for black and white home buyers. Yesterday, in part 1 of our series, we looked at a Brookings Institution report showing that homes in majority black neighborhoods sold at a 20 percent discount to otherwise similar homes in otherwise comparable neighborhoods. This systematic undervaluation of housing in majority black neighborhoods works out to a national value disparity of more than $150 billion. We took a close look at how this plays out in Memphis, a metro area with a large American population.

Housing appreciation and cyclical variability

A key question the Brooking’s report leaves unanswered is whether the black/white housing differential is larger or smaller than it was 10 or 20 years ago. If it was larger in the past and is smaller today, that implies that homes in majority black neighborhoods, although still undervalued relative to homes in predominantly white neighborhoods, have enjoyed greater relative appreciation. From the standpoint of wealth creation, the amount of appreciation since you bought your home is likely to matter more than whether the current price of your house is more or less than otherwise similar properties. Another way of expressing this is that homeowners in black neighborhoods had a lower purchase price (or basis) in their home, and even though it is still undervalued, it may have gained more value in percentage terms than homes in non-majority black neighborhoods.

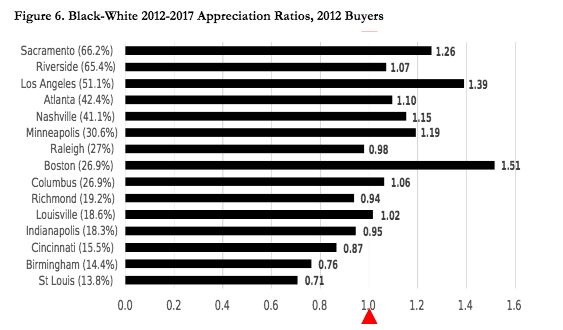

Indeed, Dan Immergluck and his colleagues at the Georgia State University found that for those who bought homes in 2012, price appreciation for black homebuyers from 2012 through 2017 was higher than for white homebuyers. Immergluck’s data show that in most markets, homes bought by black buyers appreciated more than homes bought by white homebuyers.

Immergluck’s study looks at appreciation rates for black homebuyers compared to white homebuyers, rather than in majority black neighborhoods compared to predominantly white neighborhoods. As Immergluck reports, nationally, a majority of black homebuyers bought homes in neighborhoods that were not majority black. Home prices appreciated more for black buyers in strong market cities (Boston, California) and least in weaker market cities (St. Louis, Birmingham).

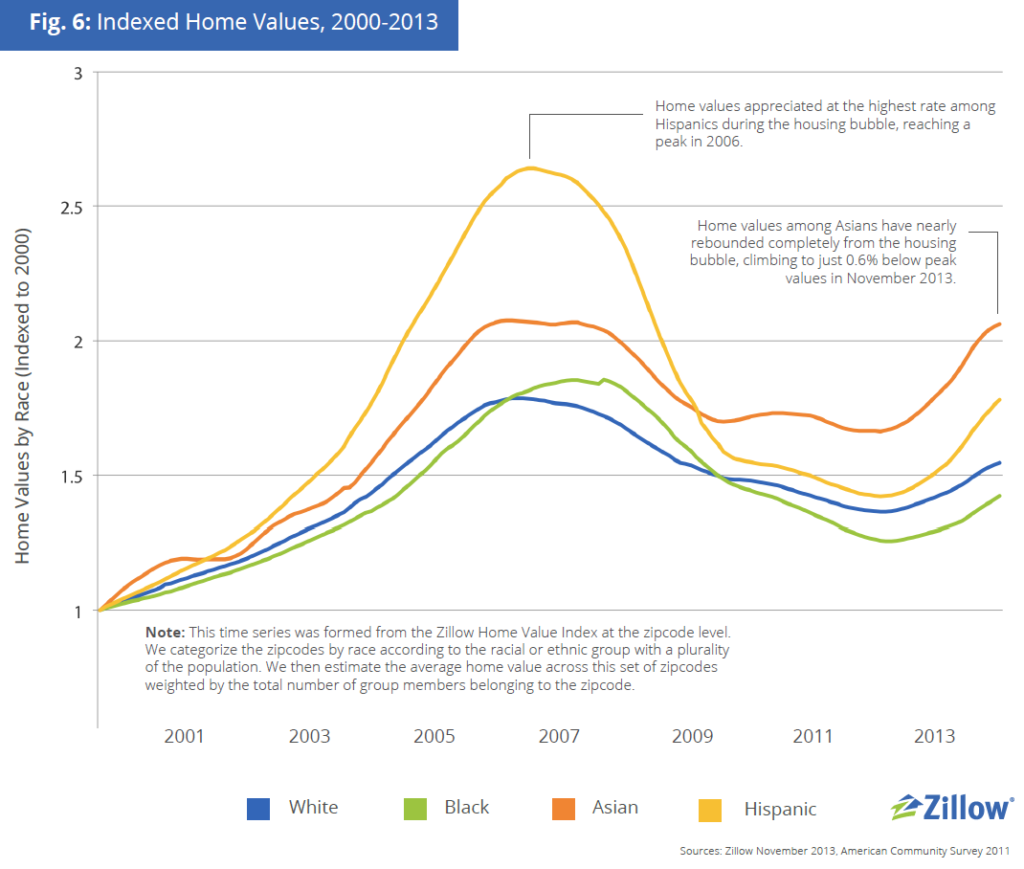

There are noticeable variations in home appreciation by race over the course of the business cycle: Zillow’s Skylar Olsen, in her report “A House Divided” plotted the change in home values by the predominant racial/ethnic group in each zip code. Her results show greater volatility for home prices in black plurality neighborhoods. Her data show home values in plurality black neighborhoods (the green line) and plurality non-Hispanic white neighborhoods (the blue line). Houses in black neighborhoods declined more in value from 2007 to 20012 ( the housing bust) than did homes in white neighborhoods.

Another recent report, written by Michela Zonta for the Center for American Progress finds that home values in neighborhoods where black homebuyers purchased homes had lower appreciation rates than neighborhoods where white homebuyers purchased homes. But Zonta’s study uses appreciation rates from 2006 through 2017, and looks at home purchases in 2013 through 2017, so doesn’t reflect the actual return enjoyed by current buyers. It’s likely that the opposite results reported by Immergluck and Zonta reflect the greater volatility of home prices in predominantly black neighborhoods (with bigger percentage declines in the bust, and bigger percentage gains the the recovery). Immergluck looks just at the recovery and finds faster appreciation in black neighborhoods, Zonta looks at the whole cycle and finds lower overall appreciation in black neighborhoods.

There’s other evidence of this cyclicality, Zillow’s data show a similar pattern for foreclosed homes, with greater volatility in neighborhoods of color. In the past five years, home values for foreclosed homes in black neighborhoods have rebounded more sharply (doubling in value) than home values for foreclosed homes in white neighborhoods. Foreclosed homes in black neighborhoods rose in price 110 percent compared to a 70 percent increase in the value of foreclosed homes in white neighborhoods.

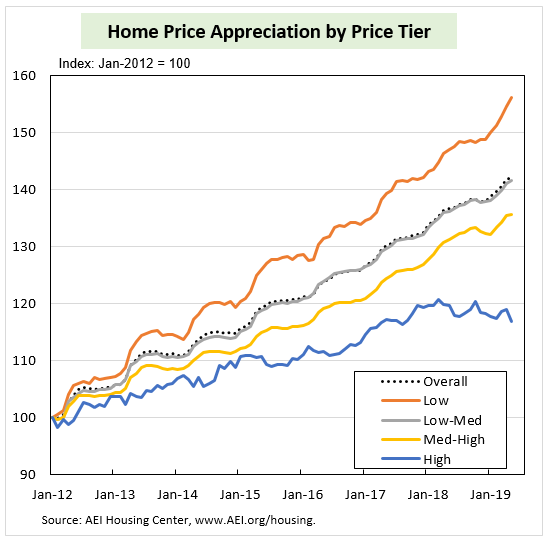

There’s also evidence of variations in cyclicality by price tier of the market. Lower priced housing tends to have greater price volatility than higher priced housing. Some of the faster growth of lower priced housing in the past few years may simply reflect that cyclical pattern and especially greater price volatility for homes in lower price tiers. According to data from the Federal Housing Finance Agency, since 2012, housing prices for lowest tier of the housing market have increased more rapidly than high tier housing. Nationally, between 2012 and 2017, homes in the low priced tier increased by about 40 percent while homes in the highest priced tier increased by about 20 percent.

If Black and Latino households are buying primarily in the lower priced tiers and white households are buying primarily in the higher priced tiers, then this may account for the difference in appreciation observed in Immergluck’s statistics..

Un-answered questions and what’s next

There’s little question that homes in black neighborhoods are systematically devalued compared to otherwise similar homes in white neighborhoods. The resulting devaluation means that homeowners in black neighborhoods have accumulated less wealth than they might have otherwise, but also somewhat paradoxically means that housing in these neighborhoods is more affordable, especially for renters. The causes of this devaluation are deep-seated and slowly changing. The fact that homebuyers, both black and white, have apparently recognized the size and persistence of this value (and appreciation) difference likely prompts investment decisions that only reinforce its existence.

In theory, we should expect the low price of equivalent quality homes in predominantly black neighborhoods to attract buyers, whether they be value-seeking white buyers who are indifferent too or actively seek out neighborhoods of color, or black households. But as Jason Segedy has pointed out, low prices may be an marker of stigma, decline or low expectations, and produce a dynamic that makes it hard to attract new buyers.

What to do about this problem is an equally complicated problem. Rising home values in predominantly black neighborhoods would represent a gain in wealth for incumbent homeowners, but would also imply at least a nominal decline in affordability. This reflects the deep-seated contradiction between our two goals for housing policy: we want housing both to be a great investment, and to be affordable. Debates over housing value disparities will always confront this obstacle.