If it can make it there, it can make it anywhere: It’s up to you New York, New York.

The big urbanism news of the past few weeks has been the debut and stunning early success of New York City’s long-delayed (and still endangered) congestion pricing system. On January 5, motorists began paying a $9 toll to enter Manhattan south of 60th Street at peak hours. As economists foretold, pricing the highly congested roadways produced immediate and material improvements in traffic.

The results are stunning. In the first three-and-a-half weeks of congestion pricing, the number of vehicles entering Manhattan declined by more than a million compared to the same period a year earlier. As a result, congestion is down, and bus speeds are up. Fewer cars also means crashes are down, and injuries are down.

Gothamist reports that he number of vehicles entering Manhattan is down, but the number of people is up.

Overall pedestrian traffic in Manhattan was up 4.6% between the Jan. 5 start of congestion pricing and Jan. 31, compared to the same period last year, according to the city’s Economic Development Corporation. Some 35.8 million people entered business improvement districts in the congestion zone, the area south of 60th Street where drivers have to pay $9 to enter during peak hours, it said. That was 1.5 million more people than during the same period in 2024, according to the findings, which were first reported by Crain’s New York Business, and follows disclosures by the MTA that 7% fewer cars entered the zone in the first weeks after congestion pricing came into effect.

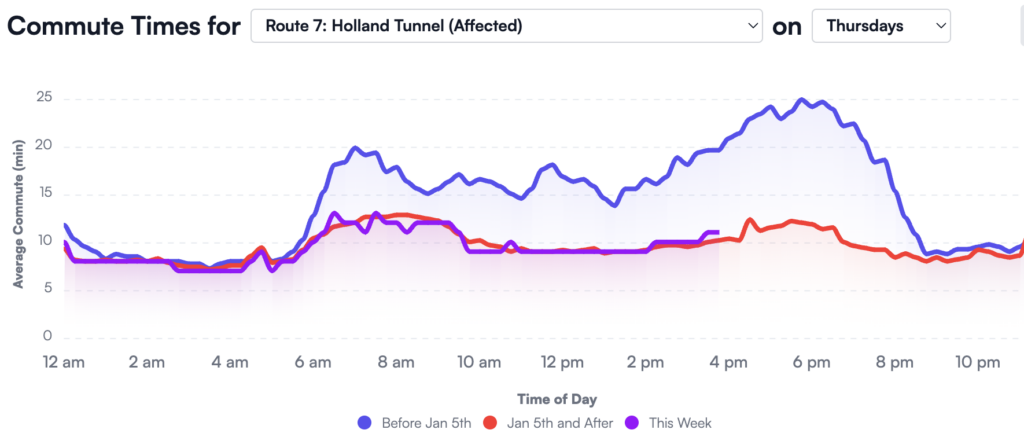

Real time traffic data confirms the improvement. The very timely website “Congestion-Pricing_Tracker.com” has detailed data showing before and after comparisons of travel times on an indicative range of Manhattan streets and highways. The Holland Tunnel, a key commuter route, shows big improvements in travel times, with 15 to 20 minute peak hour travel times falling to under 10 minutes, roughly the same as their off-peak, un-congested values.

https://www.congestion-pricing-tracker.com

To be sure, these are early days. Some of these beneficial effects may be offset by a rebound in traffic as people become used to the idea of paying for something that was previously “free.”

Value for Money

The most common objection to congestion pricing is that its merely an additional tax. But the truth is that congestion charges produce what the Brit’s call “value for money”–if you pay the fee, you get faster travel. And that’s worth a lot to those who use the roads. Here’s one of the most surprising–to non-economists, anyway–results of the NYC congestion charge. Those who are paying it strongly support it. As Paul Krugman reports:

One remarkable result of a recent Morning Consult poll is that 66 percent of adults who regularly drive into lower Manhattan support the congestion charge, while only 32 percent oppose it. The most likely explanation is that the time these drivers save from shorter commutes is worth more to them than the cost of the fee.

Safer streets, too

In addition to reducing congestion and speeding traffic (and buses), congestion pricing has had a remarkable side-benefit: fewer crashes and crash-related injuries.

. . . in the first 12 days of congestion pricing — Jan. 6 through Jan. 17, which includes 10 business days and one weekend — 37 people were injured in 90 total reported crashes, down from 76 injuries in 199 crashes over the same 12-day period in 2024. That’s a 51-percent drop in injuries and a 55-percent drop in crashes year over year.

Room for improvement

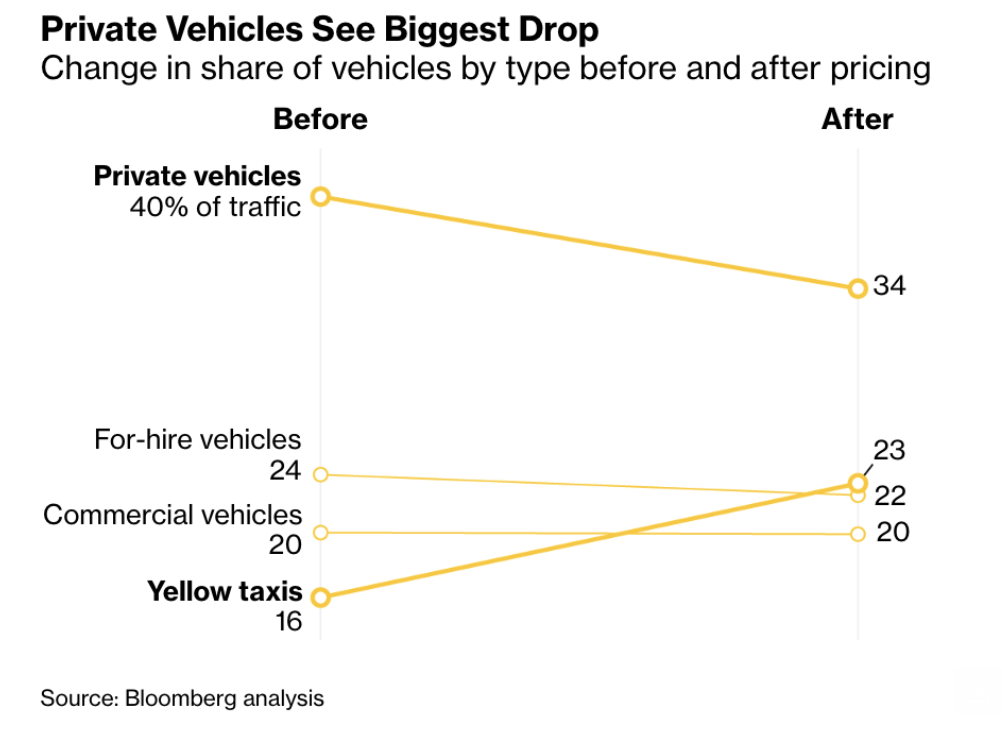

While the congestion charge, as implemented, shows that the Econ 101 explanation is right, there’s still plenty of room to tweak the charging system to produce even more improvement. Right now, congestion charging grants preferential rates to taxis and ride-sharing services. There’s strong evidence that the big gains in travel times and speeds have come on those thoroughfares frequented mostly by commuters, whose behavior is more affected by the higher congestion charge they pay. A new paper from two economists from Stanford and Chicago–Michael Ostrovsky and Frank Yang–digs into the details of the congestion charge and how its structure affects traffic patterns. Ostrovsky and Yang’s analysis concludes:

The current plan charges a high amount per trip to regular cars and a very low one to the passengers of taxis and FHVs. So in the areas where the latter type of traffic is predominant, the plan is ineffective.

The economic solution, according to Ostrovsky and Yang is to recognize the difference in congestion caused by different classes of vehicles, and adjust the fee accordingly. While the cordon pricing model works well for commuters and privately owned vehicles traveling through the congestion zone, there is much more variability in the impacts of commercial and for hire vehicles. For them, the amount of time they are being driven in congestied areas, particularly at peak hours, is the biggest contributor to congestion. So rather than a discounted, per trip fee, Ostrovsky and Yang propose that commercial vehicles be charged based on the time and distance they drive in Manhattan during peak hours.

An analysis by Bloomberg of changes in the shares of traffic within the congestion-pricing zone shows that private vehicles declined sharply as share of all observed vehicles, while for-hire, ride-hail and taxi vehicles all saw increases in share of vehicles.

Michael Ostrovsky and Frank Yang, Effective and Equitable Congestion Pricing:

New York City and Beyond, Stanford University November 12, 2024 https://web.stanford.edu/~ost/papers/nyc.pdf

While there’s not doubt room for improvement with the exact design of congestion pricing, the evidence is already abundantly clear that pricing is already a big success. Ostrovsky writes: “Having said all this, the current plan is an amazing first step in the right direction – congratulations to all the policymakers for the incredible work they put into making this happen!”

Indeed, it is difficult to think of another transportation policy initiative that has, virtually overnight, reduced congestion, improved travel speeds and made streets safer. New York’s experience shows that our urban transportation problems stem fundamentally from the fact that the price is wrong.

Of course, all this is in limbo based on Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy’s decision to purportedly revoke federal approval for congestion pricing. As of this writing, this continues to be fought out in the courts.