In cities, you’ll sometimes hear people talk about a “daytime population”: not how many people live in a place, but how many gather there regularly during their waking hours. So while 1.6 million people may actually live in Manhattan, there are nearly twice that many people on the island during a given workday.

Most studies on segregation deal with what you might call the “nighttime population,” or actual locations of residence. And of course, that kind of segregation has been shown to have significant negative effects. But it’s also in large part a matter of convenience: the Census means that we have detailed data on where people live. It’s harder to get data on where they happen to spend their time when they’re not at home.

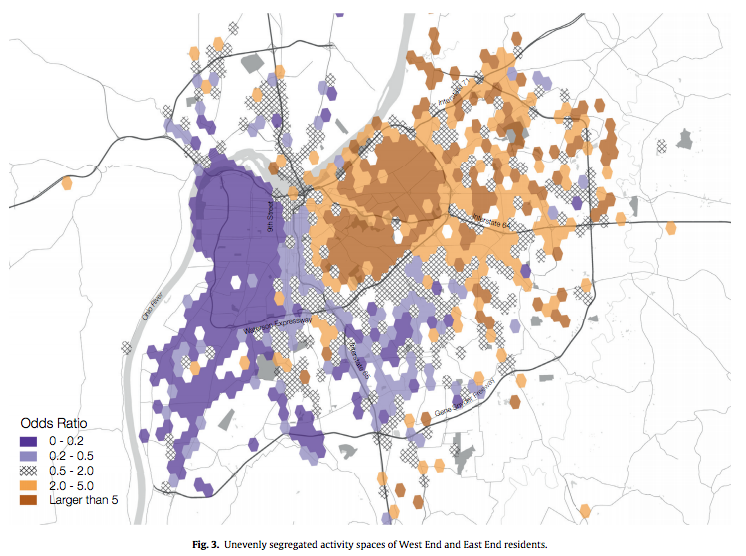

But a fascinating study asks whether, and how, waking mobility affects patterns of segregation. The authors—Taylor Shelton, Ate Poorthuis, and Matthew Zook—used geotagged Twitter and Foursquare data in Louisville, KY to determine whether users likely lived in that city’s West End (predominantly black) or East End (predominantly white). Then they mapped the ratio of the number of tweets by East End residents to the number of tweets by West End residents all across the city.

The results are striking: While the West End is visible as a block of nearly solid purple, indicating virtually no tweets from East End residents, Louisville’s East End appears as various splotches of orange, grey, and purple—indicating a much greater mix of East and West End residents.

The implication is that West End residents, who are mostly black, are much more likely to cross boundaries of segregation than East End residents, who are mostly white. In part, that may be a matter of necessity, as the wealthier East End has more jobs, stores and services.

But it also fits in a pattern of racial stigma and avoidance described by other studies as well. What’s ironic here is that while racial segregation is often described as a limitation on the movement of the disadvantaged population—and in many important ways, from health outcomes to employment, it is—in terms of physical mobility, it turns out that the driver of the West End’s isolation isn’t that West Enders never leave, but that East Enders never visit.

That dovetails with research by Ed Glaeser, who suggests that since around 1970, the persistence of “nighttime” residential segregation has been driven primarily by whites’ decisions to avoid neighborhoods that have a significant black population, and to leave their own neighborhoods when blacks move in. It also resonates with research from Robert Sampson, who found a significant stigma attached to predominantly black neighborhoods, and Maria Krysan, who found that while blacks’ knowledge about predominantly white neighborhoods in Chicago depended on their distance and economic class, whites were much more likely to describe themselves as knowing nothing about black neighborhoods, regardless of other factors.

Shelton, Poorthuis, and Zook did find that a few specific activities could draw East End residents west: a cluster appeared near the Churchill Downs racetrack during horse racing season, but then disappeared when the season ended. In other words, while this is a hopeful sign that some kinds of activities clearly generate geographic crossover, these kinds of visits appeared to be to few or limited to have any wider spillover effects in increasing even daytime integration elsewhere in the West End.

That suggests the remedy for this kind of separation will have to go deeper than just an occasional event that draws people from around the city for a few hours. But this paper helps underscore that when we think about segregation, we need to think about more than just where people sleep at night.