Today is famously “Cyber-Monday,” the day on which the nation’s consumers take to their web-browsers and started clicking for holiday shopping in earnest. Last year, its is estimated that online shoppers orders more than $3 billion worth of merchandise on this single day, and the expectation is this will grow even further this year.

The steady growth of e-commerce has many people worrying that urban streets will be overwhelmed by UPS and Fedex delivery trucks ferrying cardboard boxes from warehouses to homes. One of these jeremiads was published by Quartz: “Our Amazon addiction is clogging up our cities—and bikes might be the best solution.” Benjamin Reider notes–correctly–that UPS and other are delivering an increasing volume of packages, and asserts–without any actual data–that truck deliveries are responsible for growing urban traffic congestion.

While there’s no question that it’s really irritating when there’s a UPS truck doubled-parked in front of you–it’s actually the case that on-balance, online shopping reduces traffic congestion. The simple reason: Online shopping reduces the number of car trips to stores. Shoppers who buy online aren’t driving to stores, so more packages delivered by UPS and Fedex and the USPS mean fewer cars on the road to the mall and local stores. And here’s the bonus: this trend benefits from increased scale. The more packages these companies deliver, the greater their deliver density–meaning that they travel fewer miles per package. So if we look at the whole picture, shifting to e-commerce actually reduces congestion.

We’ve sifted through the data on urban truck transport and package delivery economics, and here are four key takeaways:

- Urban truck traffic is flat to declining, even as Internet commerce has exploded.

- More e-commerce will result in greater efficiency and less urban traffic as delivery density increases

- We likely are overbuilt for freight infrastructure in an e-commerce era

- Time-series data on urban freight movements suffer from series breaks that make long term trend comparisons unreliable.

The rise of e-commerce and attendant residential deliveries has led to predictions that urban streets will be choked to gridlock by delivery trucks. A recent article in Forbes predicted that package deliveries would triple in a few years, adding to growing traffic congestion in cities around the world.

In our view, such fears are wildly overblown. If anything they have the relationship between urban traffic patterns and e-commerce exactly backwards. The evidence to date suggests that not only has the growth of e-commerce done nothing to fuel more urban truck trips, but on net, e-commerce coupled with package delivery is actually reducing total urban VMT and traffic congestion, as it cuts into the number and length of shopping trips that people take in urban areas. The first point is that, despite the rapid growth of e-commerce, truck traffic has been essentially flat.

E-Commerce is increasing rapidly; Urban truck travel is flat

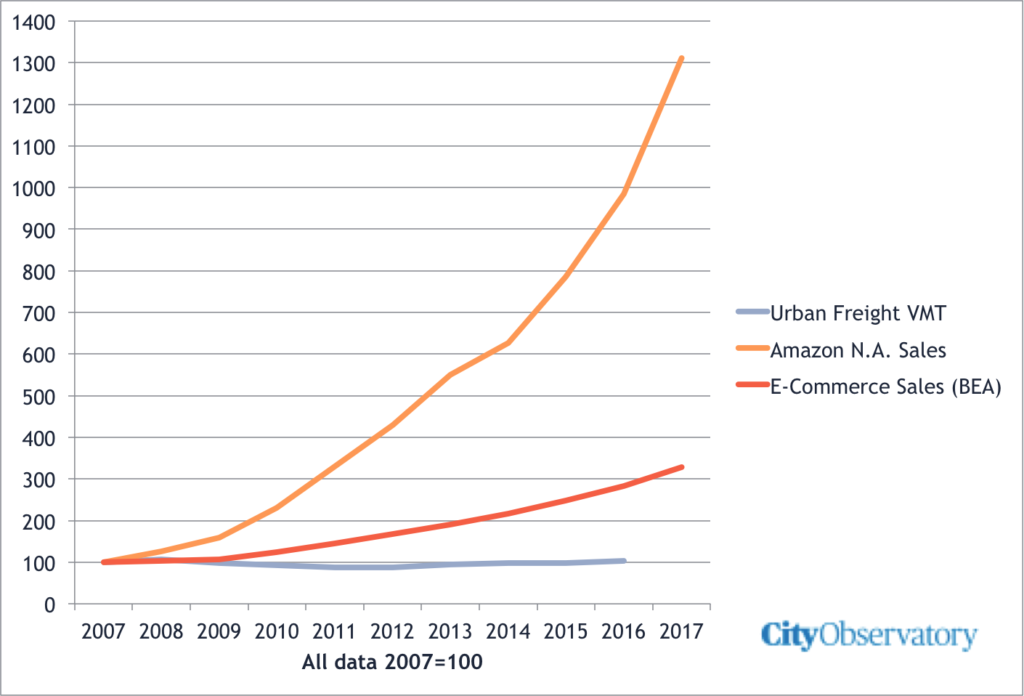

The period since 2007 coincides with the big increase in e-commerce in the U.S. From 2007 to 2017, Amazon‘s North American sales increased by a factor of 13, from $8 billion to $106 billion. Between 20007 and 2017, the total e-commerce revenues in the United States have tripled, from about $137 billion to about $448 billion according to the U.S. Department of Commerce. But over this same time period, according to the US DOT data as tabulated by Brookings, truck traffic in urban areas has increased only about 3 percent. All the increase in e-commerce appears to have very little net effect on urban truck traffic.

Does an increase in package deliveries mean increased urban traffic?

It actually seems like that increased deliveries will reduce urban traffic congestion, for two reasons. First, in many cases, ordering on line substitutes for shopping trips. Customers who get goods delivered at home forego personal car shopping trips. And because the typical UPS delivery truck makes 120 or so deliveries a day, each delivery truck may be responsible for dozens of fewer car-based shopping trips. At least one study suggests that the shift to e-commerce may reduce total VMT and carbon emissions. And transportation scholars have noted a significant decrease in shopping trips and time spent shopping.

But there’s a second reason to welcome–and not fear–an expansion of e-commerce from a transportation perspective. The efficiency of urban trucks is driven by “delivery density”–basically how closely spaced are each of a truck’s stops. One of the industry’s key efficiency metrics is “stops per mile.” The more stops per mile, according to the Institute for Supply Management, the greater the efficiency and the lower the cost of delivery. As delivery volumes increase, delivery becomes progressively more efficient. In the last several years, thanks to increased volumes — coupled with computerized routing algorithms — UPS has increased its number of stops per mile–stops increased by 3.6 percent but miles traveled increased by only about half as much, 1.9 percent. UPS estimates that higher stops per mile saved an estimated 20 million vehicle miles of travel. Or consider the experience of the U.S. Postal Service: since 2008, its increased the number of packages it delivers by 700 million per year (up 21 percent) while its delivery fleet has decreased by 10,000 vehicles (about 5 percent).

As e-commerce and delivery volumes grow, stop density will increase and freight transport will become more efficient. Because Jet.com is a rival internet shopping site to Amazon.com, and not a trucking company, its growth means more packages and greater delivery density for UPS and Fedex, not another rival delivery service putting trucks on the street.

So, far from putative cause of worry about transportation system capacity–and inevitably, a stalking horse for highway expansion projects in urban areas–the growth of e-commerce should be seen as another force that is likely to reduce total vehicle miles of travel, both by households (as they substitute on-line shopping for car travel) and as greater delivery density improves the efficiency of urban freight delivery. A study of the shopping and travel habits in the United Kingdom showed that those who used on-line shopping reduced the total number of shopping trips that they took, suggesting that package delivery stops substitute for personal shopping trips. The study concludes:

Crucially, having shopped online since the last shopping trip significantly reduces the likelihood of a physical shopping trip.

As David Levinson reports, data from detailed metropolitan level travel surveys and the national American Time Use Study show that time spent shopping has declined by about a third in the past decade. As Levinson concludes “. . . our 20th century retail infrastructure and supporting transportation system of roads and parking is overbuilt for the 21st century last-mile delivery problems in an era with growing internet shopping.”

So the next time you see one of those white or brown package delivery trucks think about how many car based shopping trips its taking off the road.