How should we view the early signs of a turnaround in Detroit?

Better to light a single candle than simply curse the darkness. The past decades have been full of dark days for Detroit, but there are finally signs of a turnaround, a first few glimmers that the city is stemming the downward spiral of economic and social decline. But for at least a few critics that’s not good enough: not content with cursing the darkness, they’re also cursing the first few candles that have been lit, for the sin of failing to resolve the city’s entire crushing legacy of decline everywhere, for everyone, and all at once.

Michigan State political scientist Laura Reese and Wayne State urban affairs expert Gary Sands have written an essay “Detroit’s recovery: The glass is half-full at best,” for Conversation which was reprinted at CityLab as “Is Detroit really making a comeback?” The article is based on a longer academic treatment of this subject by Reese, Sanders and co-authors, entitled “It’s safe to come, we’ve got lattes,” in the journal Cities. (This is one of those rare cases where the mass media version of an article is more measured and less snarky than the title of the companion academic piece, but I digress.)

Reese and Sands set about the apparently obligatory task of offering a contrarian view to stories in the popular press suggesting that Detroit has somehow turned the corner on its economic troubles and is starting to come back. We, too, are wary of glib claims that everything is fine in Detroit. It isn’t. The city still bears the deep scars of decades of industrial decline coupled with dramatic failure of urban governance. The nascent rebound is evident only in a few places.

There’s a kind of straw man argument here. Is Detroit “back?” As best I can tell, no one’s making that argument. The likelihood that the city will restore the industrial heyday of the U.S. auto industry, replete with a profitable oligopoly and powerful unions that negotiate high wages for modestly skilled work, just isn’t in the cards. As Ed Glaeser has pointed out, it’s rare that cities reinvent their economies. But when they do–as in the cases of Boston and New York–it’s because they’ve managed to do an extraordinary job of educating their local populations, and that base of talent has served as the critical resource for generating new economic activity. Detroit’s still far from that point.

And there’s no one who should think a renaissance will happen quickly if it happens at all. History is littered with examples of once flourishing cities that failed for centuries to find a second act: Athens was long deserted, Venice had its empire and economy collapse, Bruges had its harbor silt-up. In each case, these city’s early economies lived hard, died young and left a beautiful (architectural) corpse. It’s really only been in the 20th century that each of these cities revived to any degree after their historical decline.

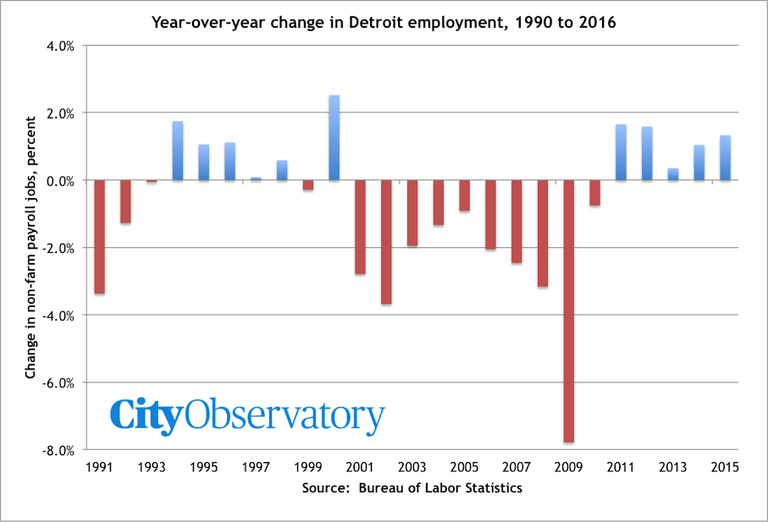

That said, there’s clear evidence that Detroit has stanched the economic hemorrhage. After a decade of year over year of job losses, Wayne County has chalked up five consecutive years of year-over-year job growth. True, the county is still down more than 150,000 jobs from its peak but has gained back 50,000 jobs in the past five years.

While this article presents a number of useful facts that remind us how far Detroit has to go, there are a lot of unresolved contradictions here. In successive paragraphs, the authors decry the lackluster performance of Detroit home prices (they’re still way below housing bubble levels and haven’t rebounded nearly as well as in other cities), but then go on to decry the unfolding gentrification of the city. You can’t have it both ways. Either housing is cheap and devalued, or the city is becoming more expensive.

Why neighborhood level equality is a misleading metric for urban well being

Reese and Sands seem to be upset that Detroit’s nascent recovery is somehow unequal; that some parts of the city are rebounding while others still decline.

“. . . within the city recovery has been highly uneven, resulting in greater inequality.”

Detroit’s problem is not inequality, it’s poverty. As the Brookings Institution’s Alan Berube put it:

“Detroit does not have an income inequality problem—it has a poverty problem. It’s hard to imagine that the city will do better over time without more high-income individuals.”

To be sure, more higher income residents and new restaurants, condos and office buildings may bring poverty into sharper contrast, but had those same higher income jobs and households located in the suburbs (or some other city), its far from obvious that poor Detroiters would somehow be better off.

As a result, the only way that Detroit is likely to improve its economy is to become at least somewhat less equal. The city has a relatively high degree of equality at a very low level of income. The reason this has occurred, in large part, is those upper and middle income households—those with the means to do so—have exited the city in large numbers, leaving poor people behind.

We’ve long called out the misleading nature of inequality statistics when applied to small geographies. What’s called “inequality” at the neighborhood level is actually a sign of economic mixing, or economic integration—a neighborhood where high, middle and low income families live in close proximity and where there are housing opportunities at a range of price points.

Incomes in central cities are almost always more unequally distributed than in the metropolitan areas in which they are located, but this is because cities are more diverse and inclusive. At small geographies, this statistic says more about integration than it does about inequality.

At a highly local level, “equality” is generally achieved in one of two ways: by having a community that is so undesirable that no one with the means to live elsewhere chooses to stay, leaving an “equal” but very poor neighborhood. Alternatively, high levels of neighborhood equality can be achieved through the application of exclusionary zoning laws that make it illegal and impossible for low (and in some cases even middle income) families to live in an area. As in some exclusive suburbs, such as Flower Mound, Texas and Bethesda, Maryland — two of the highest scoring cities on equality — the equality is only for high income families.

Indeed, the big problem in American cities, as we’ve documented in our report “Lost in Place” is that in poor neighborhoods income is actually too equal. Neighborhoods of concentrated poverty, where more than 30 percent of the population lives below the poverty line, have tripled in the past 40 years. As the work of Raj Chetty and others has shown, neighborhoods of concentrated poverty permanently lower the lifetime earnings prospects of poor kids. Otherwise similar children who grow up in more mixed income (meaning unequal) neighborhoods have higher lifetime earnings.

As a practical matter, the only way forward for the Detroit economy is if more middle income and even upper income families choose to move to the city (or stay there as their fortunes improve). That will nominally make some of the income numbers look less “equal” but will play a critical role in creating the tax base and the local consumption spending that will —gradually— lead to further improvements in Detroit’s nascent economic rebound.

Where do we start? Achieving critical mass

The second fundamental critique in the City Lab piece is an argument that the city’s redevelopment efforts are failures because they aren’t producing improvements for everyone, everywhere in the city all at once. To date, the city’s successes have been recorded in downtown, Midtown and a few nearby neighborhoods, but because other parts of the city have continued to deteriorate and depopulate, the assumption is Detroit must be failing.

This critique ignores the fundamental fact that development and city economies are highly dependent on spatial spillovers. Neighborhoods rebound by reaching a critical mass of residents, stores, job opportunities and amenities. The synergy of these actions in specific places is mutually self-reinforcing and leads to further growth. If growth were evenly spread over the entire city, no neighborhood would benefit from these spillovers. And make no mistake, this kind of spillover or interaction is fundamental to urban economics; it is what unifies the stories of city success from Jane Jacobs to Ed Glaser. Without a minimum amount of density in specific places, the urban economy can’t flourish. Detroit’s rebound will happen by recording some small successes in some places and then building outward and upward from these, not gradually raising the level of every part of the city.

Scale: Making the perfect the enemy of the good

Anyone familiar with Detroit knows that the city’s most overwhelming problem is one of operating and paying for a city built for two million people with a population (and consequently a tax base) less than half that size. The city is still wrestling with the difficult challenge of triage—reducing its footprint and shrinking its service obligations to match its resources.

And that’s the final point that’s so disturbing about the CityLab critique. Reese and Sands argue that Detroit needs more more jobs and resources for, among other things, educating its kids. No one doubts this. But where will that money come from? Certainly not from federal or state governments. It will have to come in large part from growing a local tax base, which is contingent on creating viable job centers and attracting and retaining more residents, including more middle and upper income residents.

Make no mistake: the scale here is daunting. The authors offer the helpful observation that if Detroit just somehow had another 100,000 jobs paying $10 per hour, it would pump more than $2 billion a year into the city’s economy. (Keep in mind that from 2001 through 2010, the Wayne County lost about twice that many jobs). While their math is impeccable, their economics are mystical. This is the academic equivalent of the old Steve Martin joke about how to get a million dollars tax free: “Okay, first, get a million dollars.”

It would be great if we could craft a sudden solution that would immediately create hundreds of thousands of jobs and drop billions of dollars in wages and money for schools and public services into Detroit. But that’s simply not going to happen. Instead, progress on a smaller scale has to start somewhere, has to involve new jobs, new residents and new investment in a few neighborhoods and then build from there. Businesses will start-up or move in, a few at a time, more in some neighborhoods than others, and then over time grow, providing more jobs and paying more taxes.

It’s going to be a long, hard road ahead for Detroit. And that road will lead to a different and smaller Detroit than existed in, say, the 1950s. That road is made even harder by critics that damn the first few candles for shedding too little light.