The Interstate Bridge Project falsely claimed to a legislative committee that the USDOT/Coast Guard agreement on bridge permits doesn’t apply to the IBR project.

This is part of a repeated series of misrepresentations about the approval process for bridges and the impact of the Coast Guard’s preliminary navigation determination that a new crossing must provide 178 feet of vertical clearance.

The Coast Guard’s determination is not a mere draft; under USCG regulations—agreed to by USDOT—the effect of the determination is “ruling out any alternatives that will unreasonably obstruct navigation” prior to the preparation of an Environmental Impact Statement.

IBR officials have failed to acknowledge that under the USDOT/USCG agreement, they are “proceeding at their own risk” by advancing an alternative that doesn’t provide 178 feet of clearance.

IBR’s plan is to advance only a single alternative, a fixed, 116 foot clearance bridge, and not to submit any alternatives that comply with the Coast Guard’s determination, and to dare the Coast Guard to not approve the DOTs preferred design. This is the same blackmail strategy that led to years of delay, tens of millions in added costs, and a bridge re-design for the failed Columbia River Crossing.

IBR: Misleading Statements about the Coast Guard Approval Process

IBR officials have repeatedly made misleading statements about the nature of the Coast Guard determination. They always emphasize that the Coast Guard’s action is “preliminary”—and never note that the purpose of the preliminary determination is to eliminate un-approvable options from NEPA review. IBR officials never mention that under the Coast Guard/USDOT agreement that they are “proceeding at their own risk” by advancing alternatives that don’t comply with the Coast Guard’s 178 foot preliminary determination.

And they’ve made it clear that they plan to execute the same blackmail strategy as they did a decade ago with the Columbia River Crossing (CRC), by only advancing one alternative with a 116 foot fixed span. IBR officials have also falsely implied that the Federal Aviation Administration also regulates bridge heights (it doesn’t; it can only require warning lights on tall structures). They’ve also mis-represented US Coast Guard approval standards, implying that the Coast Guard’s permitting decision will somehow be required to balance the needs of highway users with those of river users (that’s wrong: the Rivers and Harbors Act gives priority to water navigation). They’ve also implied that the Coast Guard can be placated if the IBR project pays off existing river users (the Coast Guard’s navigation determination is based on preserving navigation for future uses).

IBR officials misled the Oregon Legislature

These questions about the Coast Guard’s approval process came up at a recent hearing in Salem. State Representative Khanh Pham asked IBR officials whether the Coast Guard USDOT agreement required them to resolve the navigation height prior to the advancing to a revised Environmental Impact Statement.

On September 23, 2022, Greg Johnson and Ray Mabey testified to the Oregon Legislature’s Joint Transportation Committee that the Interstate Bridge Replacement project was not subject to the new 2014 Coast Guard MOU/MOA on procedures for approval, because it was an extension of the previously permitted Columbia River Crossing project. Essentially, they implied that it was “grandfathered” under the previous regulatory requirements. Here’s a machine-generated transcript of that hearing:

Representative Pham:

So I just wanted to clarify my question, because maybe it wasn’t as clear before, and I don’t feel like it was answered. So my question is, doesn’t the memorandum of agreement between the Coast Guard and the Federal Highway Administration require that we resolve this issue before we start the EIS process?

It does not. We are we are working with our federal partners. The Federal Highway Administration, as well as Federal Transit Administration are at the table with us. We meet with them weekly. They have signed off on the process that we are in and talking to the Coast Guard so we are not in violation of federal rules or federal processes.

Mr. Johnson, Representative Pham, Rep McClain, if I may, Ray Mabey, Assistant Program Administrator for the Interstate Bridge Replacement Program, Yes, that MOU and MOA that was created between the Coast Guard and FHWA, and FTA actually addresses new projects that are entering into the NEPA process. It does not address projects that are midstream that have an existing record of decision that are going through a supplemental and so that’s why we’re continuing to have that dialogue with the Coast Guard and our federal partners and adapting our program into that process as best we can. But yes, it did. We are not held to that same standard, but that’s why we have those ongoing dialogues with them. We know that the previous permit that we achieved, was contingent on a couple of things and that was successful agreements with the impacted users. The Coast Guard has shared with us that they believe that would be another way to achieve a permit contingent upon those agreements as well. So we think we have a path forward. And like Administrator Johnson mentioned, we are entering into dialogue with those impacted users as we speak.

(Emphasis added).

The Coast Guard has a very different view of what is required, and has said so publicly. In a recent article in the Vancouver Columbian, the Coast Guard’s regional bridge administrator explained that contrary to the IBR staff claims the revived project is subject to an entirely new process, and isn’t somehow “grandfathered” under the previous requirements.

The U.S. Coast Guard has authority over the Columbia River and other navigable waterways, with free-flowing river traffic given top priority, and a late-developing conflict over bridge heights was one of the final complications that helped scuttle the project nearly a decade ago.

Officials have learned from the experience.

“The (old) process asked critical navigation questions too late in the process,” said Steven Fischer, Coast Guard District 13 bridge administrator. “The new process gets all those navigation questions answered up front before they even submit an application.”

That new process was implemented in 2014, the year after the Columbia River Crossing fell apart. It came in the form of a memorandum of agreement between the Coast Guard and the Federal Highway Administration to coordinate and improve bridge planning and permitting.

(Emphasis added)

The basis for the Coast Guard’s statement is contained in two 2021 letters between the Coast Guard and US DOT officials which confirm that the IBR project would have to apply for an entirely new bridge permit under the newly adopted 2014 MOU/MOA. An October 13, 2021 letter from the commander of the 13th Coast Guard District, Rear Admiral M. W. Bouboulis, informed the USDOT that:

In accordance with the MOU, it is the responsibility of the Department of Transportation Operating Administration to prepare a Navigation Impact Report (NIR) for USCG review prior to or concurrent with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) scoping process. The NIR informs a USCG Preliminary Navigation Clearance Determination (PNCD), which informs the applicant’s NEPA alternatives by ruling out any alternatives that will unreasonably obstruct navigation.[Emphasis added]

. . . we want to ensure the IBR team understands the changes to the USCG bridge permit process since the 2012 Columbia River Crossing (CRC) project and understands a new bridge permit application must be submitted in accordance with the 2016 BPAG.

As the federal co-leads, we are committed to working with the USCG and the IBR Team to ensure USCG requirements and the processes and procedures outlined in the above referenced MOU and MOA are met.

These two letters make it clear that Johnson and Mabey’s claims that the MOU didn’t apply to the revived bridge project, and that there was no requirement to address the vertical navigation clearance issue prior to the EIS are simply wrong.

New Regulations in 2014 require resolving the navigation height before NEPA

The Coast Guard clearly learned its lesson from the CRC experience. They revised their permit requirements, and in 2014 entered into a new Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) with the US Department of Transportation on bridge permitting (which is binding on state highway departments as well). Henceforth, highway builders like ODOT and WDOT are required to do the navigation analysis before they undertook their final environmental impact statement. The Coast Guard would render a preliminary determination of the project’s allowable height in advance, so that both agencies would know what would be allowed, and they could avoid wasting money on plans that couldn’t be approved. (And plainly, Coast Guard was intent on keeping highway builders from delaying this step to gain more political leverage.)

The MOA between the two departments specifically provides that the preliminary determination is used to eliminate alternatives that don’t meet navigation requirements from the NEPA process. It says:

“advise which bridge designs unreasonably obstruct navigation and therefore do not require environmental analysis.

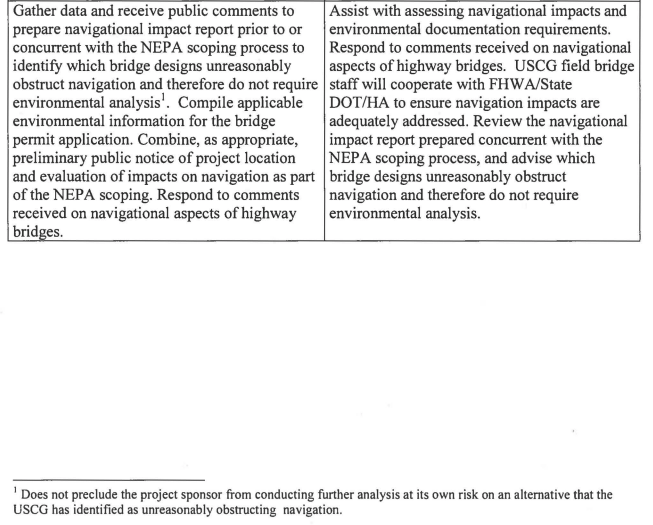

Coast Guard makes it clear that if a highway agency proceeds with plans for an alternative that doesn’t comply with its preliminary determination, that it does so “at its own risk.” (The US Department of Transportation’s responsibilities are listed in the left-hand column; the Coast Guard’s in the right-hand column).

Our PNCD concluded that the current proposed bridge with 116 feet VNC [vertical navigation clearance], as depicted in the NOPN [Navigation Only Public Notice], would create an unreasonable obstruction to navigation for vessels with a VNC greater than 116 feet and in fact would completely obstruct navigation for such vessels for the service life of the bridge which is approximately 100 years or longer.

B.J. Harris, US Coast Guard, to FHWA, June 17, 2022, (emphasis added).

From the Coast Guard’s perspective, the entire reason for accelerating the navigation impact report, and making the navigation determination now is to avoid a situation where the NEPA process studies alternatives that can’t be approved under the Rivers and Harbors Act. But the Oregon and Washington DOTs are acting like this determination has no meaning whatsoever.

Appendix: Correspondence between Coast Guard and USDOT

[pdf-embedder url=”https://cityobservatory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/USCG-Letter-to-IBR-FHWA-FTA.pdf” title=”USCG Letter to IBR FHWA FTA”]

[pdf-embedder url=”https://cityobservatory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/2021-11-23-Final-USCG-Letter-Response-FHWA-FTA.pdf” title=”2021-11-23 Final USCG Letter – Response – FHWA-FTA”]