Since 2000, home prices have grown 50 percent faster in urban centers than in their surrounding metro areas. If your are an urban data geek, like we are, this is big news. A dramatic shift in city-suburb price differentials strongly signals a deep and enduring market demand for cities.

A new research report from investment rating agency Fitch provides strong confirmation for the case we’ve been making at City Observatory: the demand for urban living is strong and increasing. Fitch calls the trend “striking” and summarizes:

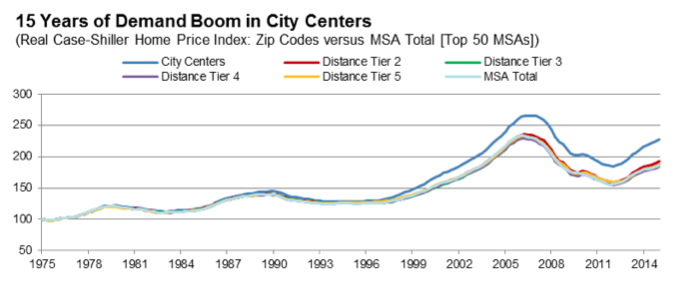

Since the mid- 1990s, demand has skyrocketed in many urban centers, with home price growth in the closest distance tiers growing at significantly higher rates than the MSAs in which they are contained.

Compiling Case-Shiller home price data for 4,600 zip codes in 50 large metropolitan since the 1970s, Fitch shows that home prices in urban centers have significantly outperformed home prices in the balance of their respective metropolitan areas throughout the country. The pattern is widespread: it holds for large and high value coastal markets like San Francisco and Boston, but also for middle sized metros like Nashville, Denver and Portland.

The Dow of Cities

Fitch summarizes its national findings in a single chart, showing how home values in the most central urban neighborhoods performed compared to successively more distant tiers of housing.

If you were to construct a “Dow-Jones” Index for cities–something that would be a comprehensive, consolidated, all-purpose summary measure of the relative economic strength of cities compared to their suburbs–it would look very much like the chart prepared by Fitch. The steady divergence between the typical home values for city centers (shown in blue; the densest and most central one-fifth of census tracts) relative to the rest of their respective metropolitan areas is striking. The chart which shows home values indexed to a 1975 base year clearly illustrates the housing bubble that peaked about 2006, and shows that while city centers also experienced absolute price declines (as did the rest of the market), they fared far better than prices in each of the four more peripheral tiers.

The Fitch analysis of relative city-suburb price trends confirms what we showed was happening in the Portland metropolitan area in a commentary we wrote last fall: in Portland, since 2005, the traditional relationship between city and suburban home values has reversed: a decade ago, city center homes sold at an 9 percent discount to those in the suburbs, now they sell at an 7 percent premium. Fitch shows this same pattern holds nationally.

Behind the price trend

The reasons behind this shift are familiar to City Observatory readers, and are laid out in several of our reports. In Young and Restless, we showed that well educated young adults (25 to 34 year-olds with at least a four year degree) are increasingly choosing to live in close-in urban neighborhoods in the nation’s largest metropolitan areas. In Surging City Center Job Growth, we showed how, for the first time in decades, employment growth in city centers was outpacing that in suburbs, in part at least, to the growing desire of firms to locate their operations closer to the preferred residential locations of young workers.

When it comes to explaining these trends, Fitch’s investment analysts sound like dyed-in-the-organic-merino new urbanists:

Updated urban planning that focuses on walkable cities, improved transportation networks and green space has improved the urban quality of life, drawing in multitudes of residents, who, in prior generations, aspired to stretches of lawn in the less dense suburban and exurban rings.

Its notable that Fitch mentions “walkable cities.” A key factor in the attractiveness of city living is walkability, and various studies have shown that increases in the walk score are associated with higher home values. The Fitch charts of city v. suburban home price disparities are strikingly similar to those generated by Zillow economists showing the relationship between walkability and home price performance. As we highlighted at City Observatory last month, within metropolitan areas, home values in more walkable neighborhoods have dramatically outpaced home prices in car dependent locations.

A big deal for the future of housing — and the suburbs

Fitch’s analysis suggests the move back to the city has important implications for the housing market. Most importantly, they don’t expect a resurgence in the falling homeownership rate:

With a trend toward increasing populations in many cities, where a far higher portion of units are rentals than in suburban areas, a return to the lofty home ownership rates seen before the housing crisis of the 2000s is unlikely . . . .

And Fitch is glum about the future of sprawling suburbs and exurbs: the shift of demand to cities implies “long run risks of declining property values in the urban periphery.”

While the strong–and in Fitch’s view, accelerating–price premium for city center living is a harbinger of robust growth in the urban core for years to come, it also signals what we think is a huge challenge for the nation. Rising prices are a clear sign that we have a shortage of cities. Many of our urban problems–especially those related to housing affordability–are directly tied to American’s growing demand for city living, and the relative paucity of places with great urban character. Higher prices are a market signal that we need more and better cities.

The full report -“U.S. RMBS Sustainable Home Price Report,Second-Quarter 2015 Update, Special Report, August 12, 2015-is available at the Fitch website.