Once again, Portland loses container service: the economic effects will be minimal.

Economic development has long been obsessed with “cargo cult” thinking: the idea that economic prosperity is caused by ports and highways moving raw materials and finished goods. That may have been partly true in the 19th Century, but today the sources of prosperity are quite different, having primarily to do with a city’s ability to aggregate and concentrate talent, to innovate and to learn. But many still cling to the simpler and more tangible icons of the past, like container ships and railroads.

This week, the Port of Portland announced that it would be ending container service at its Terminal 6 on the Columbia River. It is the second time in a decade that the Port has shuttered its money losing container terminal.

Containers in Portland: A declining and small business

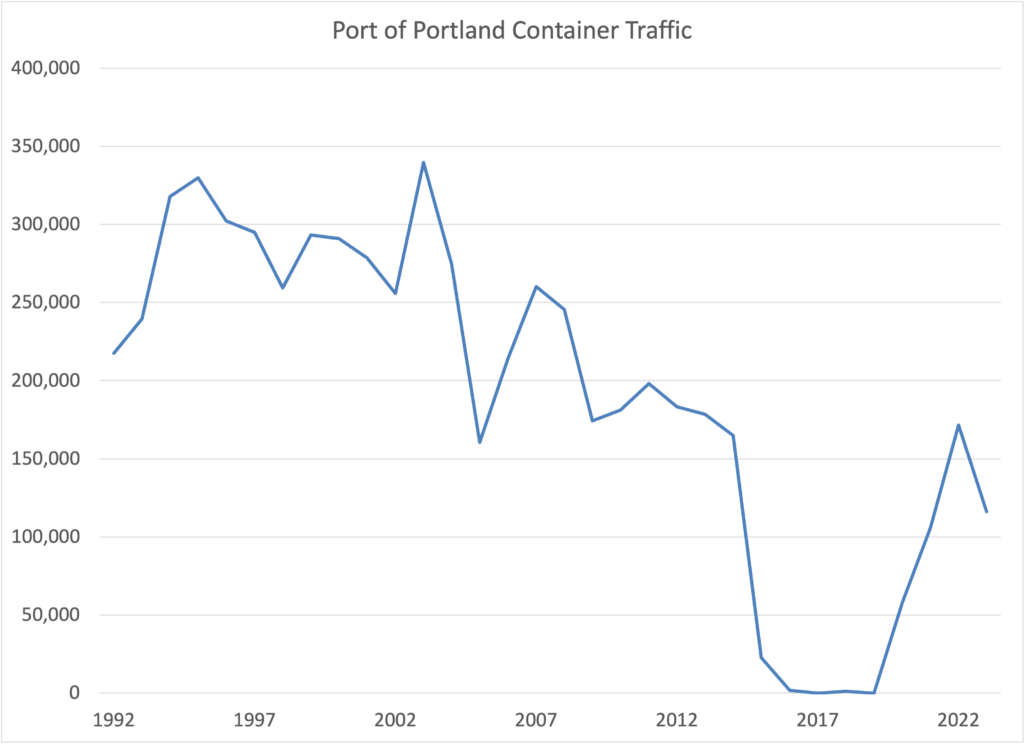

Buoyed by a brief period of panicky shipping during Covid-induced supply chain disruptions, Portland enjoyed a brief, but entirely temporary spurt of container traffic.

The truth is that Portland was never more than a bit player in the West Coast container market, peaking at about 2 percent of all West Coast container movements, and with a steadily decline in activity from the 1990s. Container traffic has increasingly gravitated to “load center” ports, like Los Angeles-Long Beach which have facilities to handle the largest container ships, and where huge facilities and frequent sailings mean that shippers get much faster and more reliable service, and can reap economies of scale.

For smaller ports like Portland, containers are a money-losing proposition: The Port of Portland lost $100 million on the container business over a decade before shutting down its container terminal in 2015. Having lost $14 million on its container operations in the past year, the Port is once again pulling the plug because it would have had to subsidize traffic to the tune of almost $100 per container to stay in the business.

The pandemic was an extraordinary moment when the global supply chains seized up, and that produced a spasm of activity to try to quickly find new ways of getting goods to market. Congestion and backlogs at major ports prompted shippers to find workarounds, leading to a brief surge in business for minor ports, like Portland. But in the past two years, conditions in the transportation and logistics markets have normalized. International freight rates, which shot up during the pandemic, have collapsed. Trucking activity has similarly gone into decline. And there’s plenty of capacity, especially in the nation’s load-center ports, to handle traffic more efficiently than ever. And going forward, the ever-growing size of containerships will further concentrate activity at the biggest ports.

An economic non-event

The good news is that container traffic isn’t particularly important to the health of the Portland economy. Moving physical stuff has long since stopped being a determining factor in economic growth.

Over the past decade, Portland’s economy has outperformed the US economy and the typical large metropolitan area, with total gross regional product increasing by nearly 34 percent, according to the Brookings Institution’s Metro Monitor.

One of the shibboleths of economic development is that we live in a “freight-dependent” economy. And while the Covid pandemic revealed the vulnerability of the global logistic system to extraordinary disruptions, these have proved, like toilet paper shortages, to be short-lived. To a certain breed of economic developers, it will always be hard to let go of the “cargo-cult” view of economic prosperity, but for most metropolitan areas, their long term success will hinge on the education level of their population, the entrepreneurship of their businesses and their ability to innovate new ideas, not the presence of container cranes.