The so-called “peak millennial” conjecture. Is it right? What does it mean? Should I care?

Time has published an article, based largely on the research of UCLA demographer Dowell Myers, proclaiming that US cities are hitting “peak millennial.” We’ve been critical of the peak millennial claims in the past. The gist of Myers argument is that we’ve seen the high water mark for the effect of millennials on urban growth, and that like previous generations, they’re going to decamp to the suburbs, and this whole “back to the city” movement will be over.

The key factoids in the Time article are the observations that the number of millennials in three cities–Boston, Chicago and Los Angeles–have declined between 2015 and 2016 according to the latest American Community Survey tabulations.

Time’s headline shouts the claim that the young are leaving cities

These Cities Have Already Reached ‘Peak Millennial’ as Young People Begin to Leave

We’re told that:

Millennials flocked to U.S. cities over the past decade, but in some places, the migration appears to be reversing . . . Myers says it’s only a matter of time before millennials head to the suburbs for more space.

What this seems to suggest is that young people have somehow become disenchanted with cities.

As we’ve pointed out, there’s a problem with equating “millennials” and “young people.” In the past decade or so, all of the 20-somethings in the United States were millennials, and most of the millennials were 20-somethings, so it wasn’t far off the mark to use to two terms interchangeably. But, inexorably, time and the aging process are moving millennials out of the “young people” category. And that’s really what these numbers show: the oldest millennials (per Myers definition) are now 36; in 2007 the oldest were just 27. There’s never been any question that there is a life-cycle effect: 36 year olds tend to be much more likely than 27 year olds to live in suburbs rather than cities.

Shifting definitions: What’s a millennial? Who’s young?

The Time Magazine article quotes data gathered by Myers using a definition of millennial as those born between 1980 and 1996, a definition he attributes to Gallup. But that’s a different definition than Myers used in the paper he published last year on peak millennials, where he said millennials were those born over a full two-decade period.

“A practical definition of birth years between 1980 and 1999 is adopted here . . .”

It’s probably inconsequential to the analysis, but is an indicator of how arbitrary the generational label “millennial” is that even a single author uses different dates to define the beginning and end of the generation in successive analyses.

In our view, looking at a single generation (or birth cohort) however defined at different points in time inherently confuses life cycle changes with generational shifts. Our preferred approach is to look at people in a specific age group, recognizing that successive birth cohorts are aging in and aging out of particular age groups all the time. This approach tells us whether young adults today are behaving differently than young adults of earlier generations. Comparing a single birth cohort’s location at two different years is really just recapitulating what we already know about life cycle tendencies rather than telling us anything about generational shifts.

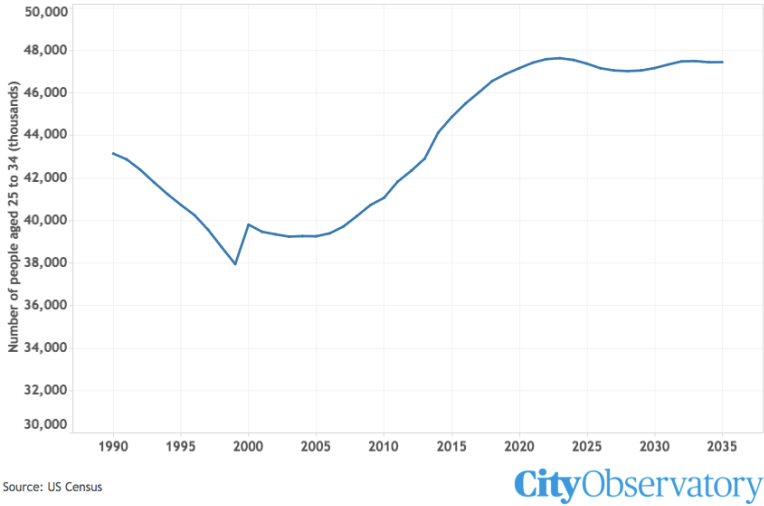

To avoid muddling the picture with life-cycle effects, it makes more sense to look at the detailed data on US population by age group, and how the number of persons in each age group will change over time. The Census Bureau predicts these numbers based on birth and death rates and estimates of net international migration. abstracting from the relatively minor effects of international migration and mortality on this age group, all of the people who are and will be young adults are here (in the US) and we can be quite confident of how many there will be in each age group in the years ahead. Focusing on prime age young adults — those 25 to 34 years old (a definition we’ve used consistently in our research for the past decade or more), we can expect a continued increase in their numbers well in to the next decade. These estimates show the number of 25 to 34 year olds plateauing, but not declining in the mid-2020s.

Picked Cherries? Millennials are still increasing in many cities.

The Time article makes much of the fact that there are slightly fewer millennials in 2016 in Boston, Chicago and Los Angeles than there were in 2015. But that’s a small sample. Is it typical? Myers notes that over the past year, Boston recorded a slight decline in its millennial population (after a solid decade of increases). There’s a pretty obvious reason why this would be the case: Boston’s demographic profile is significantly skewed by college students. It’s no surprise that Boston had more “millennials” when they were in the 18 to 34 age range in 2014, than they do in 2016 when they are in the 20-36 age range: when you excluded 18 and 19 year olds from your sample in a city with a high fraction of college students, you’re going to get a lower total..

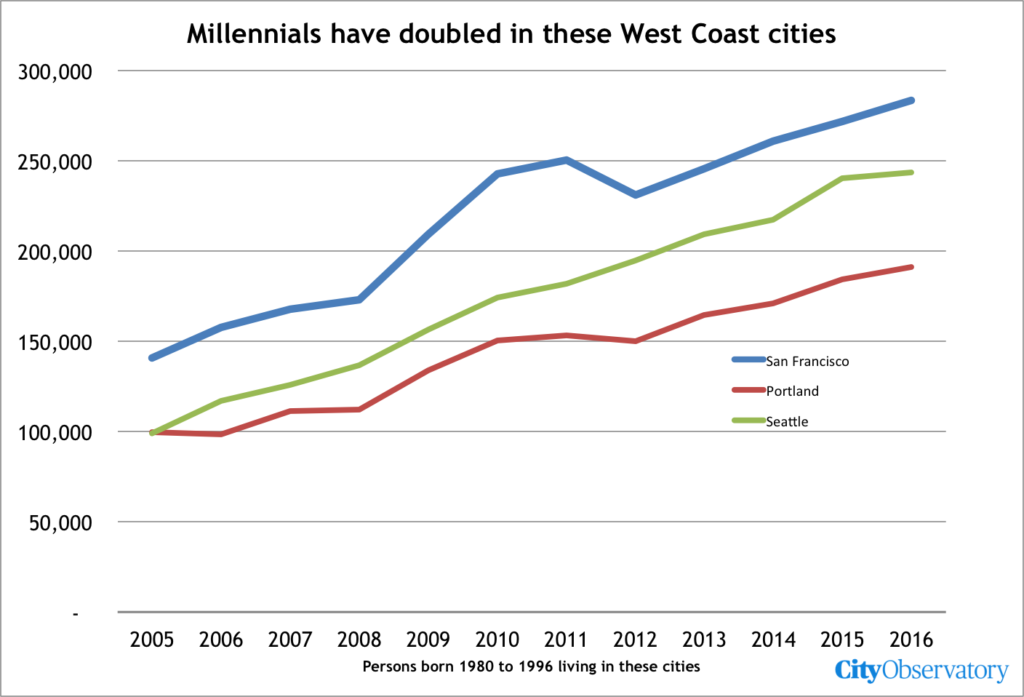

We selected three other cities (San Francisco, Seattle and Portland) to see if the same trends held for these places, which have been leading attractors of millennials. We didn’t have immediate access to the IPUMS version of the ACS data for 2016, so instead we obtained data for 20 to 36 year olds from the Census Bureau’s American Fact Finder application from the same survey. Census tabulates data by five year age group; so we interpolated values for 35 and 36 year olds. This analysis shows that the millennial population (defined as those born between 1980 and 1996) was still increasing in those three cities, after a decade in which the count of persons in this demographic had doubled in those same cities:

What’s the policy implication?

The subtext of the “millennials moving out” finding is that somehow the urban revival is drawing to a close. Those millennials, once enamored of cities, will wise up, and like previous generations move to the suburbs, ending the urban revival. But as we’ve pointed out, at every age, people in this generation are more likely to live in cities than were people earlier generations. For example, in 1980, 25 to 34 year olds were about 10 percent more likely that all adults to live in close-in urban neighborhoods; in 2010 they were about 50 percent more likely. Our finding has been confirmed by a number of academic studies (Diamond, Edlund, Sviatchi & Machado, Couture and Handbury).

In addition, if anything, the movement of now somewhat older young adults out of cities is indicative of our shortage of cities, and our failure to keep up with the high demand for urban living. Housing production is constrained in markets like Los Angeles and Boston, and the great demand of young adults to live in these cities is driving up rents. The slight decline in the count of aging millennials in some cities is less an indicator of generational disenchantment with urban living, than it is an indicator of the failure of our policies to build more housing in the kinds of neighborhoods Americans increasingly value. The number of 25 to 34 year olds in the US will continue to increase through the middle of the next decade and remain stable thereafter. Will we build the housing to accomodate them?