Alan Ehrenhalt is alarmed. In his tony suburb of Clarendon, Virginia, several nice restaurants have closed. It seems like an ominous trend. Writing at Governing, he’s warning of “The Limits of Cafe’ Urbanism.” Cafe Urbanism is a “lite” version of the consumer city theory propounded by Harvard’s Ed Glaeser, who noted that one of the chief economic advantages of cities is the benefits they provide to consumers in the form of diverse, interesting and accessible consumption opportunities, including culture, entertainment and restaurants.

While the growth of restaurants has coincided with the revival of Clarendon in the past decade, all this seems a bit insubstantial to Ehrenhalt. He worries that if the urban economic revival, is built upon the fickle tastes of restaurant consumers–as it were on a foundation of charred octopus and bison carpaccio–city economies could be vulnerable. What, Ehrenhalt worries, will happen if the growth of these restaurants peters out?

That may already be happening. In 2016, according to one reputable study, the number of independently owned restaurants in the United States — especially the relatively pricey ones that represent the core of café urbanism — declined by about 3 percent after years of steady growth. The remaining ones were reporting a decline in business from a comparable month in the previous year.

There are a couple of problems with this “restaurant die-off” story. First, its a bit over-generous to suggest that restaurants themselves are the principal economic force behind urban economic revival. The growth of restaurants is more a marker of economic activity than the driver. Restaurants are growing because cities are attracting an increasing number of well-educated and productive workers, which drives up the demand for a range of local goods, including restaurants. While the restaurants contribute to the urban fabric, they are more a result of urban rebound than a cause.

Second, the data clearly show that the restaurant business continues to expand. If anything, nationally, we’re in the midst of a continuing and historic boom in eating out. In 2014, for the first time, the total amount of money that Americans spent on food consumed away from home exceeded the amount that they spend on food for consumption at home. There may come a time when Americans cut back and spend less on eating out, but that time is not now at hand: According to Census Bureau data, through January 2017, restaurant sales were up a robust 5.6 percent over a year earlier.

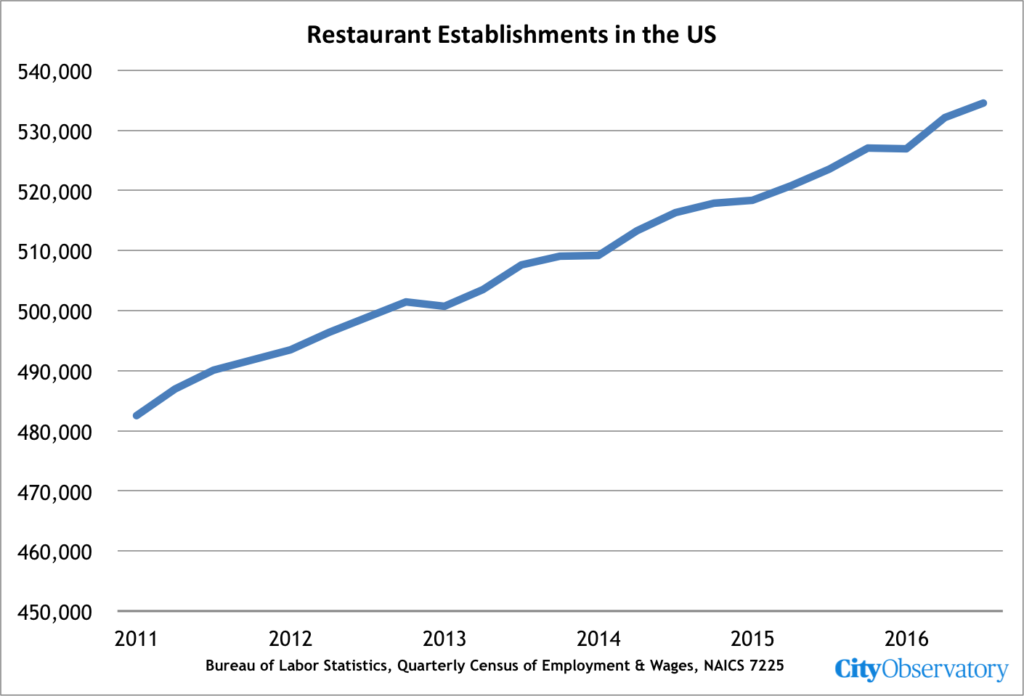

Ehrenhalt’s data about the decline in independent restaurants is apparently drawn from private estimates compiled by the consulting firm NPD, which last spring reported a decline of 3 percent in independent restaurants, from 341,000 units to 331,000 units in the prior year. NPD’s data actually compared 2014 and 2015 counts of restaurants. But the NPD estimates aren’t borne out by data gathered by the Census Bureau and Bureau of Labor Statistics, which show the number of restaurants steadily increasing. The counts from the BLS show the number of restaurants in the US increasing by about 2 percent in 2016, an acceleration in growth from the year earlier.

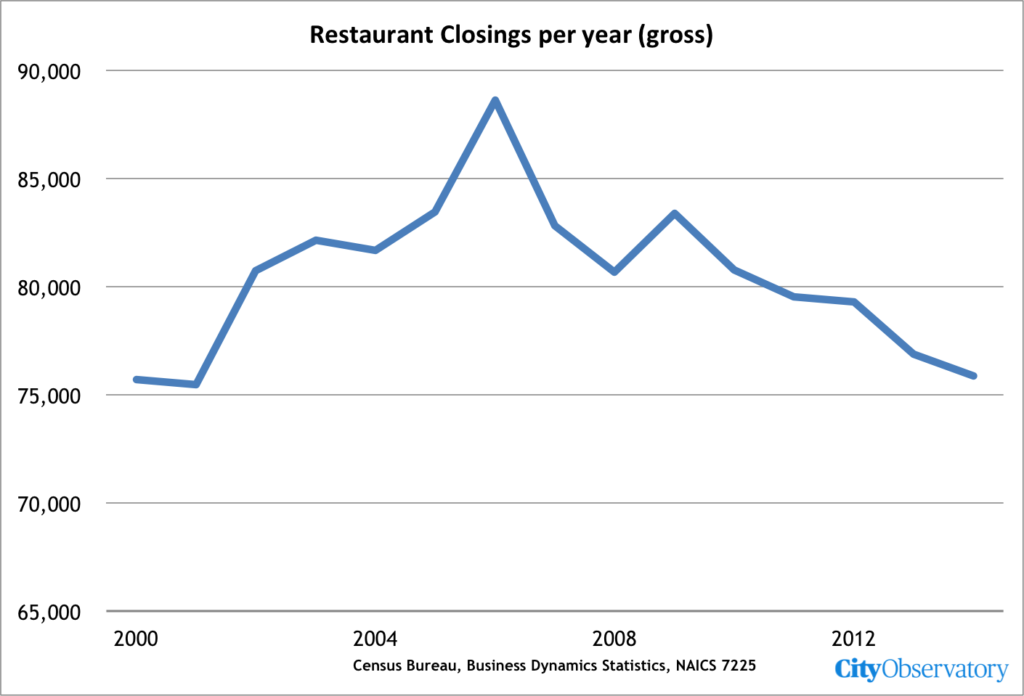

At City Observatory, we’ve seen a steady stream of articles lamenting the demise of popular restaurants in different cities, each replete with its tales from chefs telling stories of financial woe and burdensome regulation. (The reason never seems to be that the restaurant was poorly run, served bad food, had weak service, or simply couldn’t compete). The truth is failures are commonplace in the restaurant business. No one should be surprised that an industry that puts such a premium on novelty has a high rate of turnover. Government data show that something like 75,000 to 90,000 restaurants close each year, which means the mortality rate, even in good years is around 15 percent. The striking fact about the closure data is that the trend has been steadily downward for most of the past decade.

So nationally, here’s what we know about the restaurant industry:

- Americans are spending more at restaurants now than ever before, and now spend more eating out than eating at home

- The number of restaurants is at an all time high, having increased by 40,000 net over the past five years.

- Restaurant closings are common, but declining.

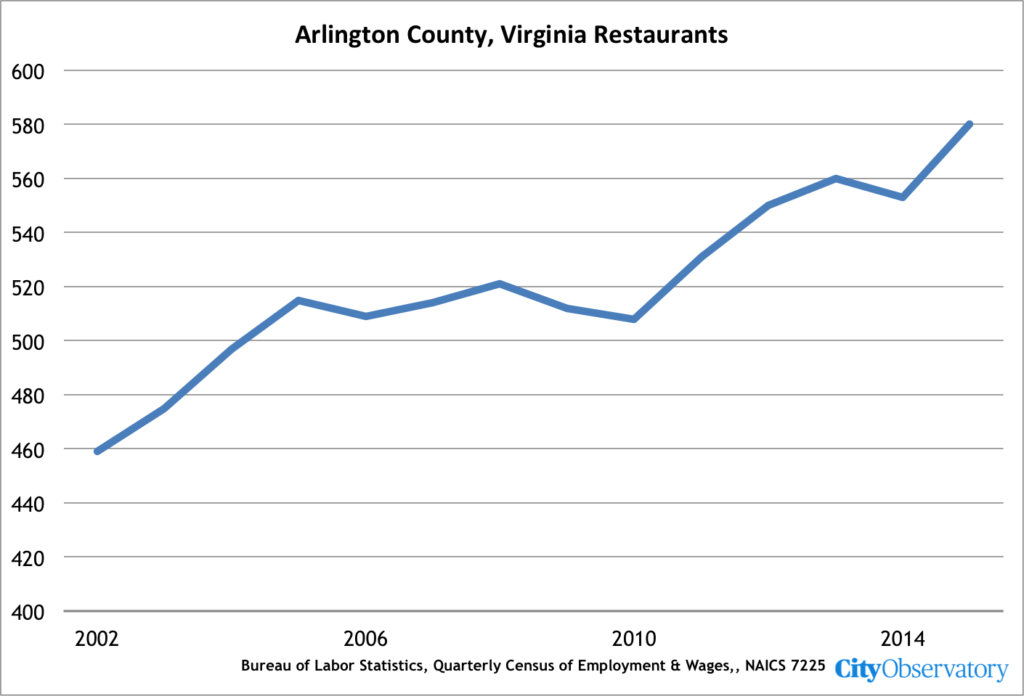

None of this is to say that Ehrenhalt isn’t right about the restaurant scene in his neighborhood. The fortunes of neighborhoods, like restaurants themselves, wax and wane. But even in Ehrenhalt’s upscale Virginia suburb, which is part of Arlington County, government data show no evidence of a widespread restaurant collapse. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that there’s been a sustained increase in the number of restaurants in Arlington County. Arlington County now has 580 restaurants, an increase of about 10 percent from its pre-recession peak.

It appears that we’re still moving in the direction of what some have called an “experience economy.” And there are few more basic (or enjoyable) experiences than a good meal. One of the economic advantages of cities is the variety and convenience of dining choices. While individual establishments will come and go, the demand for urban eating seems to be steadily increasing. So far from being a portent of economic decline, we think cafe urbanism will be with us–and continue to grow–for some time.