Another housing bubble? Strong Towns Chuck Marohn argues that we’re in the midst of another housing bubble. He claims the housing market is full of fraud and is a bubble that’s “ready to pop,” just like in 2008. Is there really a new housing bubble? Marohn’s cites the surge in house prices and worries about the “financialization” of housing.

But there’s precious little evidence of the kind of unsustainable debt-fueled price surge we experienced two decades ago. The best evidence of this is the continued decline of outstanding mortgage debt to gross domestic product. This is the best measure of our debt burden: how much we owe in home mortgage debt, relative to the size of the economy. This particular measure clearly signaled frothy housing market in the early 2000s. But today–unlike the actual housing bubble that popped in 2008–mortgage debt continues to decline relative the size of the economy. The value of household mortgage debt surged from 45 percent of GDP in 2000 to 72 percent of GDP in 2007, but has fallen steadily since then (save for a short-lived uptick during the Covid pandemic). Mortgage debt is down to well within the historical range, and seems to be edging downward; hardly evidence of a debt-fueled housing bubble.

Those of us who called the housing bubble two decades ago, saw the surge in debt–fueled by a wave of reckless sub-prime lending as a key indicator of a bubble. The fact that debt is declining is a sign this isn’t a repeat of that occurrence. A critical point is that lending standards are much tougher today than they were in the early 2000s, with most mortgages going to households with good credit.

Calculated Risk’s Bill McBride—who warned of the housing bubble in 2005—observed credit standards are very different now than they were in the days of subprime loans and “NINJA” (no income, no job or assets) loan-making that fueled the explosion of home mortgage debt. Today only 4 percent of home mortgages were made to households with FICO scores of less than 620 and the median FICO score for newly originated mortgages is 770. McBride concluded earlier this year:

The bottom line is there will not be a huge wave of distressed sales as happened following the housing bubble. Most homeowners have significant equity, were well qualified, and have a mortgage with low rates that they can afford.

Relatively few loans are variable rate mortgages, and those that are adjustable require prospective borrowers to meet tougher income standards. Real estate analytics firm Batch Service notes:

ARM products today are different from many of the products issued in the mid-2000s. Before 2008, lenders often approved ARMs based on borrowers ability to pay the initial lower interest rates. And sometimes they didn’t even check that (remember Ninja loans). Today, adjustable-rate borrowers qualify based on their ability to cover a higher monthly payment, not just the initial lower payment.

The overwhelming share of mortgage debt in the US has fixed interest rates (which has had the side effect of locking many households into their current homes, because a new home would mean a vastly more expensive interest rate). The prevalence of fixed rates, and likely Federal Reserve action to reduce rates in coming months means that there’s unlikely to be a credit crunch that triggers a decline in housing like we saw in 2008.

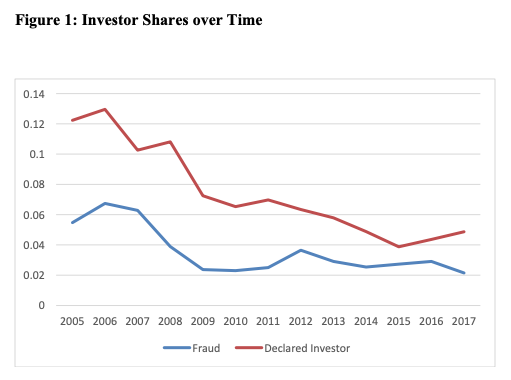

Marohn sees evidence of a bubble in some statistics on mortgage fraud, in particular, individual investors who get personal mortgages for buildings that they don’t live in. He cites a Federal Reserve Bank study illustrating the prevalence of this fraud, but fails to note that such fraudulent loans have declined by about two-thirds since the big housing bubble.

In addition, the study has no data mortgage fraud after 2017, which means that it hardly provides a basis for predicting a bubble today.

None of this is to gainsay that housing prices are high and that housing affordability is an important issue. But the problem with housing is that we’ve built too little of it, particularly in the high amenity and high opportunity urban locations that are most in demand. While it’s tempting to blame “financialization” for the woes of the housing market, the critical problem has been serious constraints on supply, especially for those kinds of housing that are most in demand. Crying “bubble” doesn’t help accurately describe the problem, or fashion a solution.