Churn means that lots of businesses, even large ones, aren’t around forever

Many of our discussions of the economy are based on simple, and often largely static mental models of the economy. In a good year, a local economy might add 2 or 3 percent to its job total, and the total number of businesses might change by even a smaller amount. But those aggregate numbers conceal a huge and continuous amount of change, both as workers move from business to business, and as businesses themselves wax and wane.

Economist Joseph Schumpeter famously coined the term “creative destruction” to describe the process by which economic improvement is the combined result of the continual formation of new firms and the death of older ones. That process is not generally revealed by our conventional economic statistics.

Any time an individual business fails, it seems like a harbinger of economic decline. Journalists are particularly prone to inflate the demise of a particular enterprise into a signal of widespread dislocation. Last week, The New Yorker wrote of “The inflated promise of the food hall,” noting that several gourmet food firms who had succeeded in one venue, found boutique food halls in other locations too costly or unprofitable.

Of more than a dozen current and former tenants I’ve spoken to, however, many have discovered that food halls are not the artisanal promised lands they seem to be.

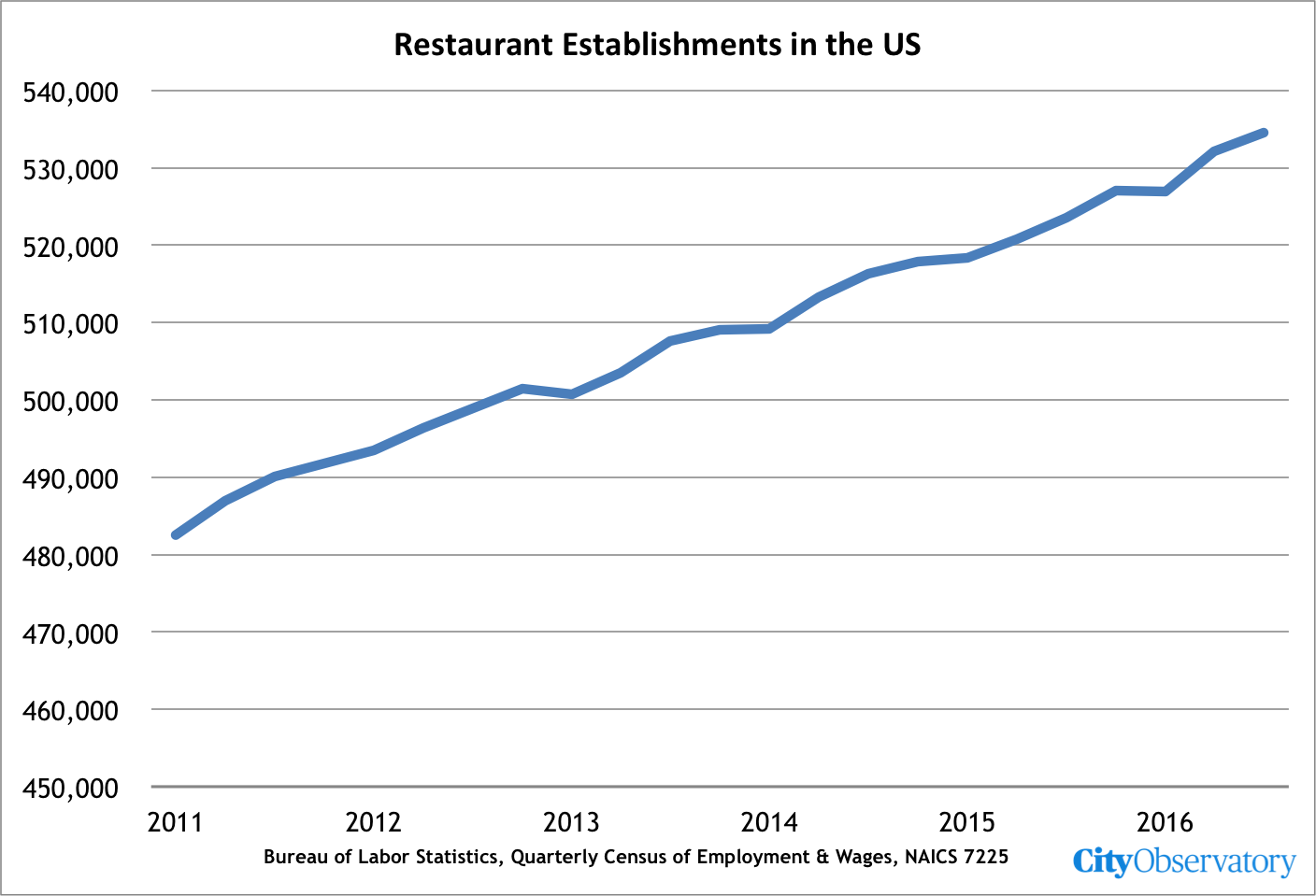

No doubt a dozen interviews is a lot of ground for a journalist, but it may not be indicative of an entire industry. The restaurant business is a famously trendy and volatile sector of the economy, with new establishments opening and older ones closely on a weekly basis. The overall trend in this industry for the past decade has been one of steady growth, but that’s something that one can confirm only by looking at the data, and by consciously looking past the demise of many once fashionable establishments. We’ve added 50,000 restaurants nationally in the past five years, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics:

A recent reminder of how volatile the economy actually is, and how much churn there is at the level of even fairly large establishments comes from a paper that uses data from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) to examine patterns of racial segregation in the workplace. (The paper–”Population processes and establishment-level racial employment segregation” is worth a read in its own right, but for today we’ll focus on one sidelight raised in this report. There’s a statutory requirement that business establishments with 50 or more employees provide an annual report to the EEOC on the race and ethnicity of their employees, so that the Commission can gauge compliance with fair employment laws. The EEOC data provide a useful longitudinal database of “large” establishments in the US. (In the vernacular of employment statistics an “establishment” is a single physical location of a particular business, like a particular store or factory; each McDonalds or Starbucks location would, for example, be a separate establishment).

You might think that these larger businesses are more likely to survive, year-to-year than all businesses, particularly smaller ones. In general large businesses are less likely to fail in any particular year. But what these data highlight is that the exit of large establishments from the EEOC rolls is surprisingly common. (What this means is that these business locations have gone from above the reporting threshold to below the threshold; some may have failed or closed, but most have probably down-sized.)

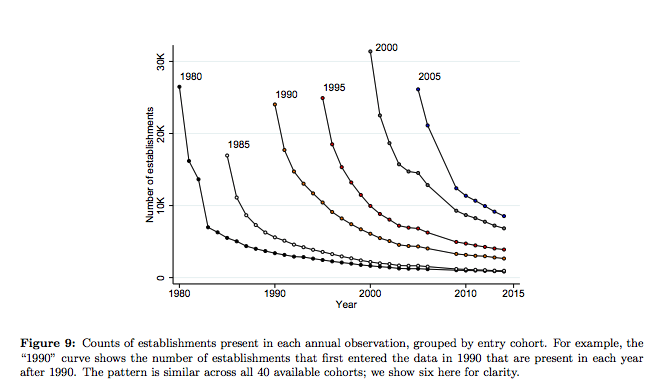

In most years, 20,000 to 30,000 establishments are aded to the EEOC rolls, with more added in times of robust economic growth (2000), than at other times. But there’s also a fairly rapid and consistent decay in these numbers in the following years. On average, half or more of the establishments added to the EEOC reporting rolls in one year no longer appear five years later. For example, in 1980, more than 25,000 new establishments were aded; by 1985, fewer than 10,000 of these were still reporting to EEOC. There’s further attrition as time passes. The are clear cyclical effects (1985 is down from 1980; 2005 is down from 2000, following recessions), but the same decay pattern holds for each successive wave of business establishments that achieves the level of employment that requires reporting.

These data are a reminder that individual business establishments–even ones with more than 50 employees–often have a relatively short life-span. We shouldn’t be surprised when we see business establishments, even relatively large ones, down-size or go out of business completely. It’s strong evidence for the continuing importance of the kind of churn and creative destruction that Schumpeter said underlies economic dynamics.