Expanding freeway capacity on I-5 hasn’t reduced crashes in Woodburn, but did triple in cost

Today, we’re pleased to offer a guest commentary from Naomi Fast. Naomi currently lives in Beaverton, Oregon. Previously, she lived in Portland, where she learned to ride a bicycle as transportation while earning graduate degrees at Portland State University. Her website is naomifast.com

In the next few weeks, metropolitan Portland will be taking a close look at an Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) proposal to spend half a billion dollars widening a mile-long stretch of I-5 near downtown Portland. ODOT is marketing the project through the release of a multi-volume “Environmental Assessment,” which makes a number of claims about how the project will influence the environment, affect traffic, and–so we are told–reduce crashes.

But as the saying goes, this isn’t our first rodeo. ODOT has been expanding capacity and widening chunks of I-5 for years. What has that experience taught us about how freeway widening affects safety, and what does it tell us about ODOT’s ability to bring projects in on time and under budget?

Previously, City Observatory has looked at a recent widening of I-5 just north of the Rose Quarter project area. But just a few years ago, ODOT completed a capacity expansion project on I-5, about 30 miles to the south, at the Woodburn Interchange. Just like the Rose Quarter, this project was pitched as a congestion-busting safety improvement. Did this project pan out as planned?

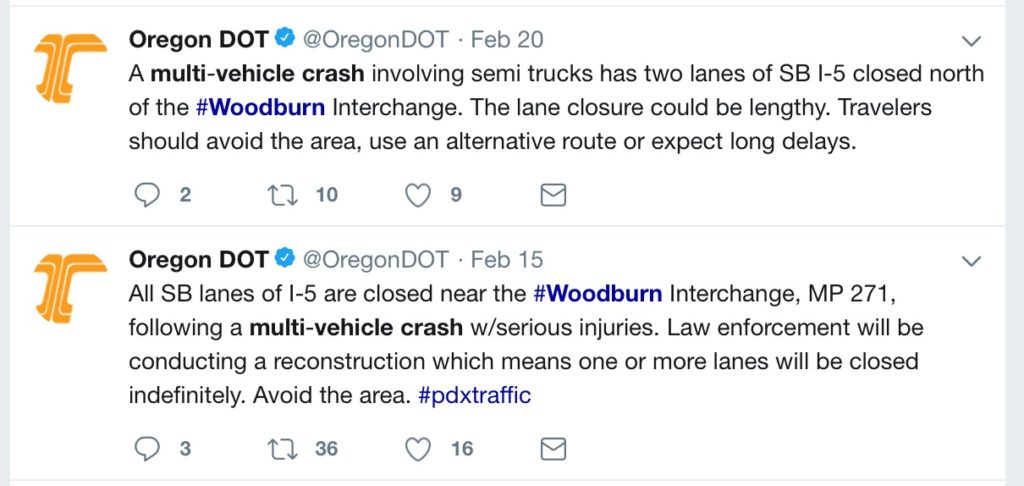

When I heard about two separate & serious multiple vehicle crashes this February at the Woodburn Interchange, each of which caused hours of delays on the I-5, I thought: Wait a minute—wasn’t that section widened recently?

As it turns out, it was. The expansion project at Milepost 271, completed in 2015, was in fact similar to in concept to the one being promoted now for the Rose Quarter. While it didn’t add auxiliary lanes like those in the Rose Quarter, it did add huge new loop ramps with long exit and entrance lanes to increase capacity to move cars on and off I-5. It had its own lengthy design process, with its own Environmental Assessment. It affected a little less than a mile of freeway, slightly smaller than the propose Rose Quarter widening, with a similar justification, and with an Environmental Assessment that compared just two options: Build & No Build.

Oregonians were told that congestion and crashes were going to be significantly reduced in that section, according to ODOT’s planning reports for the project.

- ODOT’s 2005 EA said, “Travel speeds, traffic flow, and overall safety and function would be improved for all modes of travel using the reconstructed interchange.”

- In the 2006 Revised EA report, ODOT said the widening would “provide a facility that would safely accommodate multimodal travel demands 20 years into the future.”

- A 2011 project paper said, “The purpose of the Woodburn Interchange Project is to improve the traffic flow and safety conditions of the existing Woodburn/I-5 interchange.”

- And at the 2015 ribbon cutting less than four years ago, even Governor Brown was optimistic, as seen in this video.

If improving safety is a key reason for widening freeways, then we should be looking for tangible real-world evidence that widened freeways, like the one at Woodburn, are getting safer. That means the February crashes cast real doubt on the efficacy of freeway widening and flow improvements as a safety strategy. Along with the February 15th and 20th Woodburn Interchange crashes, there have been others; there was a fatal crash at the interchange just months after it opened.

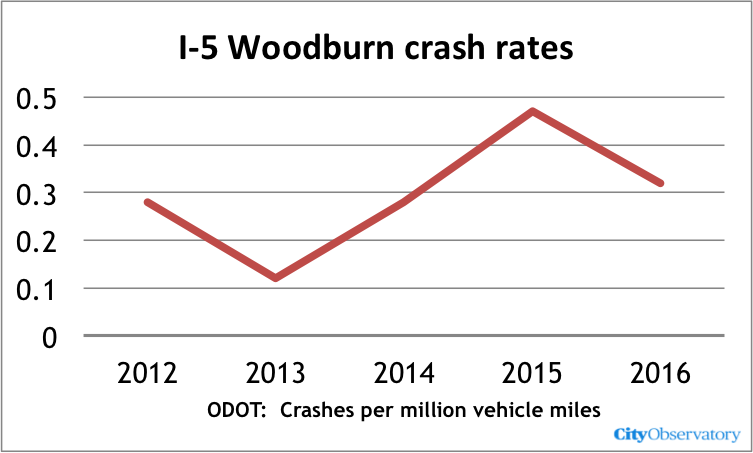

ODOT’s own annual crash data aren’t conclusive. In 2016, the first year after the project opened, and the latest year for which annual data are available, the project area experienced 14 crashes. With so few crashes (less than one per month, on average) crash rates can vary a lot from year to year. The data so far suggest that the crash performance of this area is no better than it was before the project was built. It remains to be seen how last month’s crashes will figure into the 2019 totals, but two in a little over two weeks is a lot.

ODOT’s own annual crash data aren’t conclusive. In 2016, the first year after the project opened, and the latest year for which annual data are available, the project area experienced 14 crashes. With so few crashes (less than one per month, on average) crash rates can vary a lot from year to year. The data so far suggest that the crash performance of this area is no better than it was before the project was built. It remains to be seen how last month’s crashes will figure into the 2019 totals, but two in a little over two weeks is a lot.

There’s one other thing to consider: While highway engineers almost always think its a good thing if traffic can move faster, safety analysts point to crash data that shows that speed is strongly associated with more crashes and more severe injuries. The real world experience with widening Interstate 5, both here in Woodburn, and to the north of the project between Lombard and Victory in Portland, shows that contrary to the claims of engineers, there’s no reason to believe that wider freeways will have fewer, or less severe crashes.

How much will it cost?

There’s a postscript to the Woodburn Interchange story. Not only does it not appear to have delivered improved safety, it’s also ended up costing vastly more than promised. When initially proposed by the Oregon Department of Transportation in 2005, the project was supposed to cost $25 million (according to the project’s 2006 Environmental Assessment). When finally completed in 2015, the project’s cost had nearly tripled to more than $70 million. In the case of the Rose Quarter–a much more complex project, in a dense urban setting–imagine if $500 million were to nearly triple.